Postal Updates

Recalling the First Continental Congress of 1774

Delivering the Mail by Allen Abel

“I almost wish to live to hear the triumphs of the Jubilee in the year 1874 to see the medals, pictures, fragments of writing that shall be displayed,” an excited but anonymous patriot wrote in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet during a tumultuous summer of grievance and audacity, exactly two and one-half centuries ago.

Thirteen North American colonies soon would “dissolve our connexion [sic] with Great Britain,” the writer prophesied, and the rebels’ heirs would memorialize their boldness in song and story a hundred years in the future. The patriot’s forecast might have been off by 24 months — we honor the Spirit of ’76, not ’74 — but the addictive aroma of revolution already was in the air.

In Annapolis, Md., an importer whose ship, the Peggy Stewart, arrived laden with 2,000 pounds of “the detestable weed tea,” was forced by “the Fury of a lawless Mob” to burn the vessel to the waterline.

In Edenton, N.C., 51 women resolved “not to drink any more tea, nor wear any more British cloth, (having) determined to give a memorable proof of patriotism, and to shew [sic] ... how zealously and faithfully American ladies follow the laudable example of their husbands.”

And at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, Pa., 55 delegates from 12 of Britain’s New World possessions were convening a Continental Congress and whispering what long had been unthinkable, while one — Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island — was daring to proclaim that “The gun and bayonet alone will finish the contest in which we are engaged, and any of you who cannot bring your minds to this mode of adjusting the quarrel, had better retire in time.”

“The die is cast,” wrote Abigail Adams to a friend. “Poor distressed America. Heaven only knows what is next to take place but it seems to me the Sword is now our only, yet dreadful alternative.”

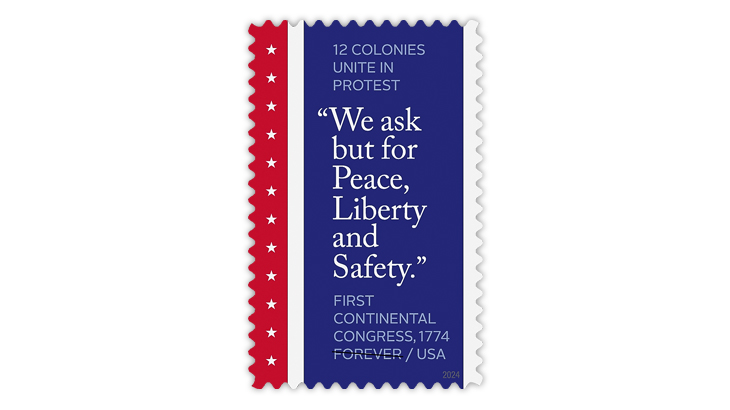

The Philadelphia Congress wrapped up in Oct. 1774. “We ask but for Peace, Liberty, and Safety,” the delegates wrote to King George III in a phrase that would be quoted on a 1974 United States 10¢ postage stamp (Scott 1544) and again on a nondenominated (73¢) commemorative stamp that will be issued Sept. 5.

[Editor’s note: For more details about the First Continental Congress stamp being issued Sept. 5, see the story in the Aug. 26 issue of Linn’s.]

The colonists appealed to their “most gracious Sovereign, in the name of all your faithful People in America, with the utmost humility, to implore you, for the honour of Almighty God.” But their supplication, Benjamin Franklin reported from London, “came down among a great Heap of letters of Intelligence from Governors and officers in America, Newspapers, Pamphlets, Handbills, etc., from that Country, the last in the List,” and it is unlikely that the Sovereign ever even saw it.

Instead, George III, who never in his 60-year reign visited Scotland, Wales or Ireland — let alone North America — warned Parliament that “a most daring spirit of disobedience to the law still unhappily prevails in the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, and has in divers [sic] parts of it broke forth in violences of a very criminal nature.”

“You may depend upon my firm and steadfast resolution to withstand every attempt to weaken or impair the supreme authority of this Legislature over all the dominions of my Crown,” the king warned.

Or, as Lin-Manuel Miranda summarized the king’s intentions in the theatrical play Hamilton, “when push comes to shove, I will kill your friends and family to remind you of my love.”

But what if the die had not yet been cast in the summer of 1774? What if George III had studied Congress’ appeal, been moved by the grievances of the ladies of North Carolina, summoned his ministers and said, “Let’s make a deal?”

Linn’s put this intriguing question to Alexis Tobias-Jacavone of the Edenton Historical Commission and to the eminent Cornell University historian Mary Beth Norton, whose book 1774 – The Long Year of Revolution won the prestigious George Washington Prize in 2021.

“In my personal opinion,” Tobias-Jacavone replied by email, “had the King responded positively to the petitions sent by the Continental Congress, it is likely that the status quo would have been maintained for a while longer, but unless there was a radical change in the Crown’s administration of the Colonies (such as impactful representation in Parliament), the American Revolution would have still happened eventually.”

“There might have been a delay while the colonies and Parliament and the ministry went back and forth as John Adams had predicted before Boston got news of the Port Act,” Norton responded.

“But in the long run,” Norton concludes, “the different conceptions of the imperial relationship were too deep to be papered over and there would have been a rupture. The differences were unresolvable.”

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers

-

World Stamps

Oct 5, 2024, 1 PMCanada Post continues Truth and Reconciliation series

-

US Stamps

Oct 4, 2024, 6 PM86th Balpex show set for Oct. 25-27 at new location

-

World Stamps

Oct 4, 2024, 2 PMUnited Nations Postal Administration marks International Day of Older Persons