US Stamps

Depreciated currency markings and economic hard times

By Labron Harris

In my August column, I wrote about domestic mail and pictured covers addressed within the United States. This month, I’m writing about international mail — in particular, depreciated currency covers. But first, I need to provide some background on the subject of early overseas mail between the United States and foreign countries.

From the time they arrived in this country, early colonial settlers began writing to their homelands. This mail was carried overseas on a ship, either by an individual as a favor, or by the captain of the ship, who was compensated for this service.

In the 1800s, the United States began entering into treaties with other countries to set postal rates to be paid for mail carried to and through each treaty partner. Such mail could be sent prepaid, or unpaid with the addressee paying on receipt.

International letters known as depreciated currency covers came into being as a result of the inflation caused by the Civil War.

Congress passed a bill in 1861 to authorize the U.S. Treasury to print and issue demand notes to help finance the debt incurred by preparations for the rapidly approaching war. In 1862 these demand notes were replaced by U.S. notes, commonly called “greenbacks.”

People had become accustomed to using coins (known as specie) to transact their business, and they had little confidence in the new greenbacks. As a result, the value of the greenback fell against the value of specie.

This created a crisis in many areas, and in unpaid international mail in particular.

If a post office accepted greenbacks for payment of unpaid postage on incoming letters and then, under the various treaties with foreign countries, had to pay the specie value to those countries, it lost the difference in value between the specie and the inflated greenbacks.

On April 1,1863, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair issued a circular to postmasters instructing them to only accept gold or silver coins for payment of postage on unpaid mail from Great Britain and Ireland, France, Prussia, Hamburg, Bremen or Belgium. Other countries were later added to this list.

If the individual wanted to pay with greenbacks, he had to pay the amount at the depreciated (inflated) currency rate. For example, an unpaid letter from England would be due 24¢ in specie. If currency was worth half as much, then the recipient would pay double the amount in greenbacks: 48¢.

This policy became effective May 1, 1863, and the first trans-Atlantic crossings under this system were later that month.

The ratio of currency to specie peaked at more than 2½-to-1 in 1864.

Covers showing ratios of greater than 2-to-1 are not common and are a good addition to a depreciated-currency collection.

U.S. ports of entry appear on these covers, with cancels from New York and Boston being the most common, followed by Portland (Maine) and Chicago in scarcity, with Detroit being very scarce and Baltimore being rare.

The early cancels not only bore the name of the port of entry but also the nationality of the carrying packet (ship); either British, American, Hamburg, Bremen or French.

Early depreciated-currency covers were canceled with circular cancels enclosing the port of entry, the country’s packet carrying the cover, and the depreciated currency rating. The specie amount appears on the top of the cancel, and the currency (notes) on the bottom. These cancels were applied at the port of entry.

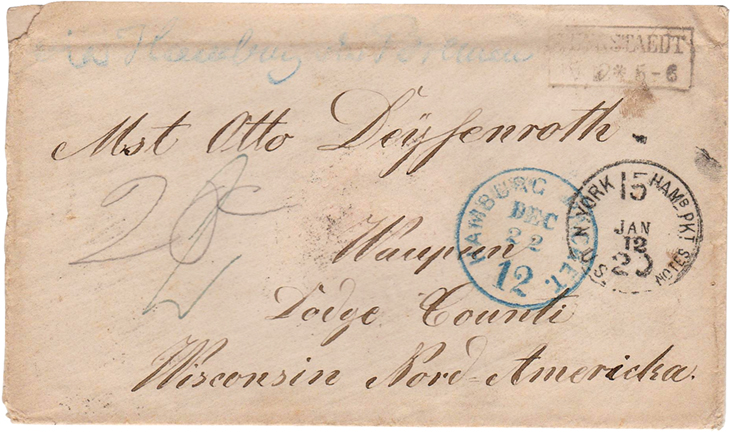

Shown is a cover from Germany carried on a Hamburg packet. The blue circular marking at right indicates 15¢ in specie due, with the black circular marking showing 20¢ in currency due.

Later the depreciated currency markings changed. No longer included was the amount of the rate in specie marked; the marking was fixed only in currency or, as it was alternately called, notes.

Straight line cancels such as IN US NOTES appeared for the currency amount due.

Large and small circles with the amount due and the words IN CURRENCY or IN NOTES or some variation became prevalent.

The 1866 cover from France shown here is shortpaid and therefore considered unpaid. It was carried by a British packet (indicated by the truncated blue box) with a round blue Chicago port-of-entry marking and the due marking of 20¢ IN NOTES (the rate in specie was 15¢).

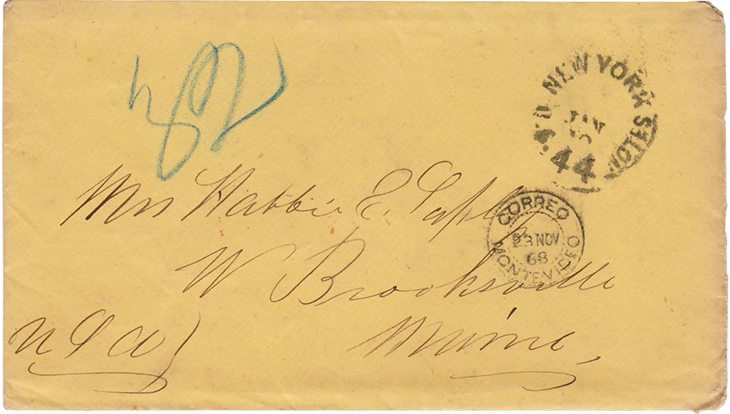

The cover from Montevideo, Uruguay, was mailed to Brooksville, Maine, in 1868. It is struck with the depreciated currency marking NEW YORK/US 44 NOTES, indicating 44¢ due in U.S. notes. At upper left is a manuscript blue 32 indicating 32¢ due if paid in specie.

Depreciated-currency markings were used on covers into the late 1870s, even though the ratio of the value of currency to specie became small, and was finally equivalent.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

World Stamps

Oct 10, 2024, 12 PMRoyal Mail honors 60 years of the Who

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 3 PMProspectus available for Pipex 2025

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 2 PMGratitude for Denise McCarty’s 43-year career with Linn’s

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 12 PMWorld’s first butterfly topical stamp in strong demand