US Stamps

How the blue sky turned gray on some 1989 $2.40 Moon Landing stamps

U.S. Stamp Notes by John M. Hotchner

Modern stamp printing, especially multicolor printing, is complicated. And as with your car or washing machine, the more complex the equipment is the more things that can go wrong.

Because of the complexity, when a color variety comes out of the printing process, it is easy to misdiagnose. In this column, I will discuss a variety of the $2.40 Priority Mail Moon Landing 20th Anniversary stamp of 1989 (Scott 2419) with a gray instead of dark blue sky in the background. This stamp was produced by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

Figure 1 shows a normal example with a dark blue background at left, a mint example of the gray background variety in the center, and a used example of the variety at right.

Notice that the mint example of the variety appears fresh, while the used example has discolored paper and an overall darker appearance. The former is as purchased from a post office. The used example was likely altered from a normal example of the stamp.

Customers who purchased this $2.40 stamp at post offices said they received the gray version of the stamp in a few instances. When they reported the variety within the hobby, they swore the stamps were as received; they had not altered them in any way.

Early reports suggested that the blue in the sky had not printed, and that this was a missing-color error. That proved not to be the case, but it took a review and explanation by the BEP to establish what did happen.

Expertizers trying to figure out the gray variety of the stamps purchased at post offices knew that they were printed by a combination of methods. The part of the design produced from engraved plates included the black detail in the figures of the astronauts.

The rest of the design was printed using lithographic plates to apply black, yellow, red, the light blue in the flag, and the dark blue of the sky. Note that there was no plate assigned to print gray, and that the dark blue color was applied as dark blue, not as a combination of other colors.

This told expertizers that there was no color missing, but that something had changed the dark blue to gray. Normally, such a change would have been a human-caused alteration after stamps were purchased from the post office. But there were the troublesome and consistent reports that the gray stamps had been sold by post offices.

Jacques C. Schiff Jr. (1931-2017), a professional auctioneer and an expertizer for the Philatelic Foundation who had good contacts at the BEP, agreed to take samples of the gray variety to Washington, D.C., to ask the BEP staff their thoughts on the matter.

Here are his notes from that visit:

“First I had them show me the printing records. There was no indication that grey was used along with or instead of the dark blue. This meant the color was chemically altered. Assuming this was done after USPS sale was very disturbing. I could not imagine how anyone could possibly do such a good job since none of the other colors were altered.

“Next I showed the variety to a press foreman whom I know. He studied the stamp with high power magnification to no avail. He sent for another foreman whom I knew. This man had supervised the printing of the stamp.

“Ron was able to provide the answer we were seeking. Chemicals used to wipe the press at the BEP had altered the color. Stamps altered were marked for destruction, but some escaped.”

So, despite being a variety cased in the production of the stamp, it was later determined that the change could be reproduced by chemical means or by exposing normal stamps to sunlight or fluorescent light for varying lengths of time. For that reason, Scott catalog editors decided not to give it error status, but there is a note explaining the variety in the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers.

The note reads: “No 2419 exists with a gray background instead of the normal dark blue. Some of these may have been caused by a chemical wiping of the blue plate. However, the same or extremely similar stamps can be produced by exposing normal stamps to sunlight or fluorescent light for varying time periods.”

Beware

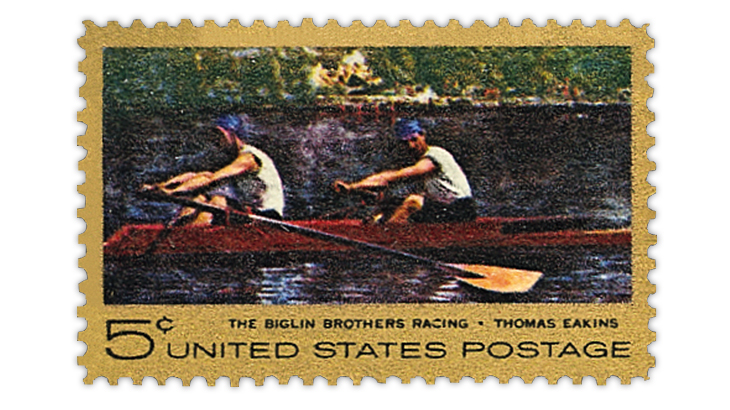

The 1967 5¢ Thomas Eakins stamp depicts his oil painting The Biglin Brothers Racing, framed by a gold border (Scott 1335).

Figure 2 shows a normal example of the stamp, and Figure 3 shows the front and back of an example with a border that appears to be green instead of gold. This plate number single was listed and pictured in Regency-Superior’s January 2014 Orcoexpo auction with an estimate of $300.

Is this an error? My immediate response was “no way.” With 50 stamps in a sheet, there would be plenty of these to go around if it were a genuine (and expensive) item. Most knowledgeable collectors would identify it as an altered stamp, a curiosity worth keeping, but hardly a pricey rarity.

The lot description for the stamp read:

“Very fine and unusual bottom margin plate number single (#29276 and #29280), showing GREEN border rather than GOLD. Interior of stamp design area also shows light flaking. Tagging appears to be undisturbed, making tampering unlikely. Green ink shows characteristics of non-metallic standard printing ink, likely negating any type of ink contamination or color changeling. Since Eakins stamp was first U.S. stamp produced by photogravure, production was contracted out to ‘Photogravure & Color Co.’ of New Jersey. Is this a possible test piece or essay? MINT never hinged.”

The lot did not sell.

I have seen the occasional example offered in the marketplace, usually as an unexplained oddity. And I am aware of at least one submission of a full pane to the Philatelic Foundation asking for a finding as “gold omitted.”

In the Philatelic Foundation case, I asked Len Piszkiewicz for his thoughts. Piszkiewicz is an accomplished collector and a former editor of the United States Specialist, the journal of the United States Stamp Society. He also holds a doctorate in organic chemistry from the California Institute of Technology.

Here is a slightly edited version of his response:

“Gold paint [or ink in this case] is not gold leaf — it is a paint that is made with a brass pigment to look like gold. It does tarnish, like brass does, and develops the greenish color in evidence here. You cannot remove this without removing the paint because the paint itself has changed color.”

He continued: “If the stamp ink contained brass pigment to make the gold color, then exposure to an oxidizing agent could oxidize the copper in the pigment turning it green (think the +2 valence state of copper that usually gives green coloring — think of old copper roofs and bronze statues in parks that turned green in the weather). Exposure of mint stamps to a gaseous oxidizing agent — maybe something like chlorine — could give a uniform green color like in the picture, even leaving original gum. Give me a well equipped lab and a couple weeks, and I could probably figure out what would work.”

After due consideration, the Philatelic Foundation issued certificate No. 559998, saying “…we are of the opinion that it is not Scott 1335 Variety. Rather it is a never hinged Scott No. 1335 with all colors present and the original gold ink changed to ‘green’ due to its exposure to an unknown source.”

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 3 PMRoyal Mail’s Oct. 1 definitive meets new international standard rate

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 12 PMPostcrossing meetup Oct. 9 at U.N. headquarters

-

Postal Updates

Oct 7, 2024, 5 PMUSPS plans to raise postal rates five times in next three years

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest