US Stamps

National Bank Note Co. pursued methods to prevent reuse of stamps

By James E. Lee

In April 1861, the events in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina changed the course of history. The ensuing four-year American Civil War would tear apart the fabric of our republic.

Something as simple as a postage stamp would become a grave concern for the United States Post Office Department. Montgomery Blair, President Lincoln’s postmaster general, realized that the Southern states possessed large quantities of United States postage stamps.

These stamps in the enemy’s hands, Blair and others knew, could be used to finance the Southern cause.

Thus there was a need for new stamps of a different design to replace the current issues, which would then be demonetized.

An additional concern also surfaced about the same time. It was believed that citizens could wash the cancels off stamps and reuse them.

So deep was this concern that the Post Office Department sought ideas for the improvement of postage stamps to the point where they could not be reused.

The newly minted stamp contractor, the National Bank Note Company of New York City, was made aware of the department’s concern.

National Bank Note was charged with the responsibility of improving the stamps to the point that they could not be reused. But the firm did not immediately move on the task.

However, several men who possessed both the entrepreneurial drive and an inventive bent came forward with ideas to prevent reuse, and then turned these ideas into patents.

National Bank Note soon realized these ideas were a threat to the company’s contract. By November 1864, National knew the time had come to act.

This month’s column focuses on these men, their patents, and the solution that allowed National to hold onto the contract.

Henry Lowenberg received a patent for his Decalcomania idea in 1864, and the U.S. Treasury had granted him a contract to produce 10,000 revenue stamps that were to be produced using his patent.

The Decalcomania essays were printed on the back of goldbeaters’ skin paper, with gum on the design side.

During the course of the next three years, George Bowlsby, William Wyckoff, Abram Gibson, and Samuel Francis would put forth patented ideas for improving and preventing the reuse of postage stamps.

What is interesting is that each of their ideas was tested in offline production. In each case, the National Bank Note Co. prepared the plates and conducted the tests.

It is my belief that National actually bought up the patents to keep the inventors from taking away the stamp contract.

At the same time, Charles Steel, one of National’s employees, was working on an idea that would become the solution that the Post Office Department actually bought — the grill.

The grill, a waffle-like pattern pressed into the stamp paper to make it harder to remove cancellation ink, did not come into use until 1867.

The Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers lists many of these experimental items considered by National. The ones that showed the most promise are profiled in the balance of this month’s column.

Abram J. Gibson of Worcester, Mass., was granted patent No. 41,118 dated Jan. 5, 1864, for printing stamps with fugitive ink that would dissolve if the canceled stamp was immersed in water. This was one of two patents awarded to Gibson.

The other patent involved a starch coating similar to the type used in Henry Lowenburg’s Decalcomania patent.

Illustrated nearby is a block of four of the plate essay for the 1861 3¢ Washington printed using Gibson’s fugitive ink (Scott 79-E25h).

Henry Lowenberg of New York City received patent No. 42,207 dated April 5, 1864, for his process involving application of a starch coating (or “size”) to the paper before printing. This would prevent the printed stamp image from penetrating the paper.

Once such a stamp was canceled, any attempt to “wash off” the cancel would cause the design to dissolve and disappear. As we shall see, William Wyckoff improved on this process in 1866.

This process was used on the trial color proof block of four of the 1861 1¢ Franklin (Scott 63TC5) pictured here.

Lowenberg also received patent No. 45,057 dated Nov. 15, 1864, for an early example of the process we know today as the decal. In fact, he called it the Decalcomania.

Once affixed to an envelope, the stamp could not be removed without destroying it.

One could call Lowenberg the father of the prevention of reuse of postage stamps, because it was his contract with the U.S. Treasury Department that set off the race.

Pictured nearby is a block of four of the Decalcomania essay for the 1861 90¢ Washington (Scott 79-E72P5).

Samuel Ward Francis of New York City was granted patent No. 48,389 dated June 27, 1865, for a process that involved, according to the patent, “soaking the stamp paper with ferro-cyanide of potassium (before printing) and combine sulphate of iron with the gum. Any attempt to wash the stamp would produce a stain of a deep blue color, which will permanently deface the stamp.”

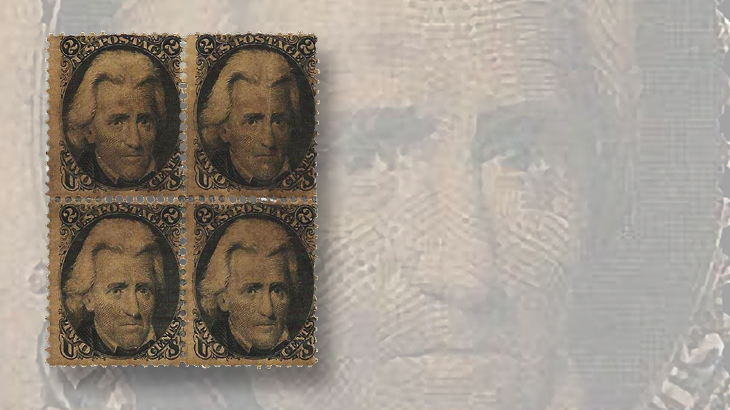

Francis’ patent essay for the 1861 2¢ Andrew Jackson, in a block of four, is illustrated nearby. This essay is not listed in the Scott U.S. Specialized catalog.

George W. Bowlsby of Monroe, Mich., received patent No. 51,782 dated Dec. 26, 1865, for a method of reuse prevention known to collectors today as the “coupon essay.”

Bowlsby’s idea involved a stamp with a tab to be removed by the postmaster at the time of canceling and mailing. The stamp was gummed, and the attached tab was not.

Shown here is a perforated block of four of the Bowlsby coupon essay for the 1861 1¢ Franklin (Scott 63-E13f).

Note that there are perforations between the stamp and the coupon. Bowlsby essays also exist imperforate between the stamp and coupon (Scott 63-E13g), and with roulettes between the stamp and coupon (63-E13h).

William C. Wyckoff of Brooklyn, N.Y., received patent No. 53,722 dated April 3, 1866, for a method that called for applying a layer of so-called “Chinese white” watercolor pigment to the surface of the paper and then printing the stamp on top of the pigment.

Any attempt to remove the cancel would cause the design to dissolve and disappear.

A Wyckoff trial color proof block of four of the 1¢ Franklin in blue-green is shown nearby (Scott 63TC5j).

Charles F. Steel of Brooklyn, N.Y., was superintendent of the manufacture of postage stamps for the National Bank Note Co.

Steel was the father of the grilling process (for which he was granted patent No. 70,147 dated Oct. 22, 1867) the Post Office Department elected to add to the production process.

Steel would receive a royalty from his employer, and National Bank Note was assured of continuation of its contract to produce postage stamps.

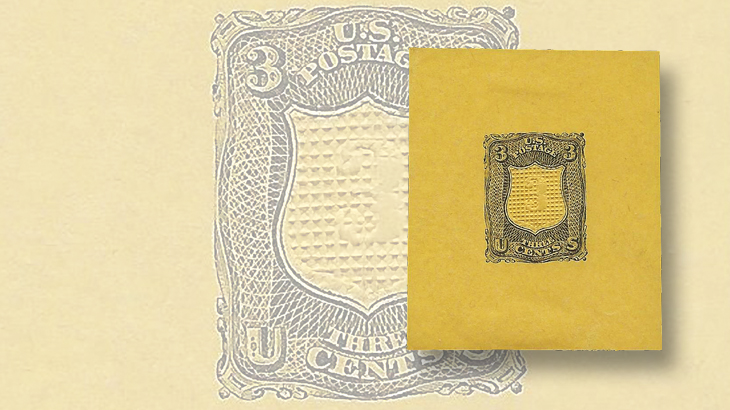

A die essay for the 1867 3¢ Washington on yellow wove paper, showing a grill and an embossed “3,” is shown here (Scott 79-E18e).

There were more than 50 patents awarded from 1864 into the late 1870s for the improvement of postage stamps. Only Steel’s grill would see mass production. However, the production of grilled stamps was discontinued in mid-1870.

My March column will provide more information on Charles F. Steel, the grilling experiments, and the various other patents that he received and were tested.

James E. Lee has been a full-time professional philatelist for more than 25 years, specializing in United States essays and proofs, postal history and fancy cancels. He may be reached via email at: jim@jameslee.com or through his website: www.jameslee.com.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

World Stamps

Oct 10, 2024, 12 PMRoyal Mail honors 60 years of the Who

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 3 PMProspectus available for Pipex 2025

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 2 PMGratitude for Denise McCarty’s 43-year career with Linn’s

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 12 PMWorld’s first butterfly topical stamp in strong demand