US Stamps

Specialist expertizers, a critical resource and a double-edged sword

U.S. Stamp Notes by John M. Hotchner

Linn’s reader Sid Morginstin of Bordentown, N.J., recently wrote to present an expertizing ethics problem. He is a specialist expertizer, which I define as an independent solo performer with expertise in a specialized area, oftentimes a dealer as well.

Morginstin fits that definition. He runs the Negev Holyland Auctions and is a specialist expertizer in the postal stationery of Israel and some other related Holy Land areas.

In his message to me, Morginstin makes the point that he does not issue certificates, but others do, and that is the crux of the problem he writes about:

“For example, Joe B is a recognized expert in the postal history of Upper Slobovia. He is active in its society. There are not many dealers who handle Upper Slobovia. Joe B happens to be the largest such dealer. I have no problem with him issuing a certificate on an item. However, I do object to Joe B then offering that item for sale.

“Ancillary to this, I am also afraid that if one of Joe B’s competitors sends him a very rare item for a certificate, Joe B may state that it is ’not genuine’ so that the competition does not get the publicity or business.

“Now the question arises: what if Joe B is the only recognized expert in Upper Slobovia? Do we have to trust him? What can be done?”

I have several reactions. It is certainly a given that there is an opportunity for mischief when a single individual accumulates power through knowledge. That said, and I am no Pollyanna, it’s my experience that the dealers and collectors in our hobby are honest to a degree greater than the general population.

Thus it is my baseline expectation that specialist experts can be relied upon to do the right thing when applying their knowledge in rendering opinions on stamps and covers submitted for expertization. For one thing, they are proud of their knowledge and their reputation and do not want to put the latter in jeopardy.

As I have said before in this column, I am a fan of multiple sets of eyes examining any patient (a stamp or cover submitted for expertization), but in some collecting areas this is not possible.

In the case where a specialist expertizer has a financial interest in an item being expertized, there is indeed potential for mischief, and I can understand why Morginstin would not want a dealer to be selling something he or she had determined to be genuine.

On the other hand, if the dealer stands behind the certificate to the extent that he guarantees a refund within a year or so of purchase should a competent authority determine that the item is not as described, I would not object to the expert selling the item on his own behalf or that of another owner.

Indeed if he is the only expert and the primary dealer in the field, I as an owner would want him to be the seller. It would disadvantage me if the dealer said: “Yep, it’s genuine all right. Now, here’s your certificate. Take it elsewhere to sell it. I can’t because some think if I sold it, it would be a conflict of interest.”

So, as with so many things in this life, clear yes and no answers can be elusive, and we are forced to contend with shades of gray and to make decisions on incomplete information. There are some guidelines, though, as follows:

a. Is the expertizer/dealer a member of professional organizations, such as the American Stamp Dealers Association or the American Philatelic Society, entities that have codes of ethics such that membership indicates a clean ethical record?

b. Is the expertizer/dealer a member of the relevant specialist organization or organizations? Does he contribute articles to the society journal? This speaks well to both level of knowledge and to the level of respect in which he is held.

c. Does the expertizer/dealer also expertize for one of the expertizing institutions in the United States or abroad?

d. Can the expertizer/dealer provide references regarding his operations?

e. Does the expertizer/dealer have a printed statement of qualifications and a statement of the services provided, specifying fees, his responsibilities and your rights? Specialists who hold themselves out to be an expert for hire should have such statements.

f. If the expertizer/dealer accepts material consigned for sale or operates an auction, be certain to read the terms of sale carefully. There should be no surprises after the sale.

Once you have done your homework and feel good about the services and terms, you may also feel confident that you can move forward.

You must still keep in mind that an expertizing opinion, whether from an expertizing organization or from a specialist expertizer, is just that: an opinion. Much as we are tempted to look at opinions as conclusive, they are the best opinion that can be reached at a moment in time based on knowledge, reference material and the tools available.

So one other thing to look for in any expertizer is a healthy level of humility in addition to a healthy level of self-confidence. Specialist expertizers especially (since no one is checking their work) must know when they are in over their heads, when to seek help and when to decline an opinion.

The motto of every first-class expertizer is “Seek certainty — and distrust it. Never guess!”

Beware

The fact that a given stamp is genuine as described on a good certificate does not necessarily mean that its selling price ought to be anything near catalog value. There is the matter of condition to be assessed, especially when it comes to imperf classics.

Ancient wisdom does not go out of style, and the following passage from Chats on Postage Stamps by Fred J. Melville, published in 1911, is worth remembering:

“… with old used stamps, especially the imperforates, really fine copies cannot always be got at the prices indicated for them in the standard catalogues. … the beginner would be well advised to choose even his (apparently) common stamps with painstaking regard to their perfection of condition. …”

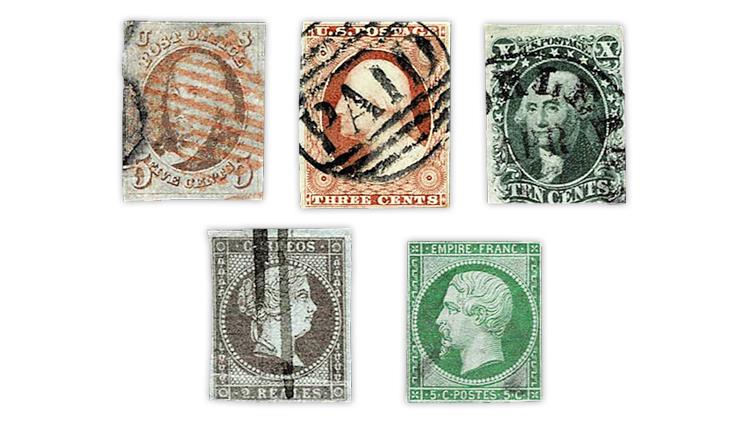

What this means is that lightly canceled, undamaged stamps with four margins, such as those from the United States, Spain and France shown in Figure 1, are unusual and command a premium. Only a small percentage of existing stamps meet this standard.

Most of these early imperfs were separated by scissors or a knife or by using a ruler. Postal personnel paid little, if any, attention to the collectability of the stamps they were selling. So most do not have four margins, and even lightly canceled examples were often pinned to a sales board by a dealer before reaching a collector.

The result is that after running the gauntlet of separation, cancellation and retailing to collectors, precious few perfect early stamps exist. Most look more like the examples from the United States, Spain and France shown in Figure 2.

So you may be surprised to see perfection priced near or even above catalog value, but what you should guard against is paying those sorts of prices for the types of stamps shown in Figure 2.

Pricing of stamps can sometimes represent the triumph of hope over reality. In fact the fewer the margins, the less perfect the condition and the heavier the cancel, the faster the retail price should fall as a percentage of catalog value.

The harsh reality is that an average example of even a scarce stamp should be priced a good deal less than catalog value, even as low as 5 to 10 percent for a sound but flawed stamp with one or two margins, a heavy cancel and damage.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 3 PMRoyal Mail’s Oct. 1 definitive meets new international standard rate

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 12 PMPostcrossing meetup Oct. 9 at U.N. headquarters

-

Postal Updates

Oct 7, 2024, 5 PMUSPS plans to raise postal rates five times in next three years

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest