Insights

insights

Difficult covers fun to collect, challenge to decipher: Stamp Collecting Basics

By Janet Klug

Stamp collecting is a versatile hobby that includes not just stamps but also many different kinds of covers: envelopes or folded letters that have gone through the postal system.

Collecting covers as postal history is a lot of fun, and it also can be quite challenging. The fun of covers, especially difficult ones, is in working out where they went, how they got there and why.

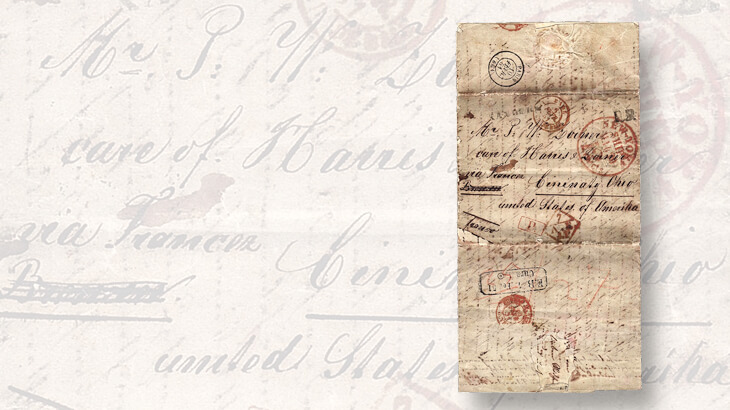

For example, look at the envelope shown in the first illustration. It is a cover sent from South River, N.J., on July 26, 1918, during World War I. The postmark gives us the place and date of mailing information.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Look at all the accumulated markings on the cover and you realize that the 3¢ Washington stamp on the envelope got a lot of mileage.

The sender’s return address is on the envelope’s back flap: M.E. Holm of Milltown, N.J. The sender wrote the name of the intended recipient, Private Wm. R. Appleton, on the front of the cover, followed by an address in seemingly different handwriting, in black (and crossed out): “Motor Field Hospital #36, Camp Greenleaf, Chickamauga Park, Georgia.”

Above Appleton’s name is written, in red, “motor Fld. Hosp. #36.”

In the upper-left corner there is a blue-penciled inscription that reads: “No Record/Training at School/for [san.? for sanitary?] troops 8/31.”

Now what?

A first step might be to find out more about Camp Greenleaf.

The United States Army Medical History website states, “In May 1917, it was ordered that a training camp to be named Camp Greenleaf was to be established at Fort Oglethorpe. The training camp was for medical officers.”

The camp was to be ready for occupancy on June 1, 1917, and enlisted men were later sent to Camp Greenleaf and placed in groups for training. One of the groups was for those men who would be in a motor field unit. Perhaps Private Appleton did get training at the Motor Field Hospital #36 at Camp Greenleaf, but then what?

At the bottom-left corner of the cover is another address: “Block L.L., Barracks 14, F.11, Camp Merritt, N.J.” Perhaps this was the next stop after Camp Greenleaf for Appleton.

Camp Merritt was a base that was used to assemble and deploy troops heading for the Western Front during WWI. Was that Appleton’s destination? Rubberstamped in black over Appleton’s name and the first line of the address is a marking that states, “FORWARDED A.E.F. [American Expeditionary Forces], VIA N.Y.”

This letter, along with certainly hundreds or thousands more, was bagged up and placed on a ship heading toward Western Europe, where William Appleton apparently was headed. In dark blue pencil at the top of the cover is the number 793. That could be an Army Post Office (APO) number, or perhaps something else. APO 793 serviced the 7th Division, but was not established until Sept. 21, 1918, according to The Postal History of the AEF, 1917-1923 edited by Theo Van Dam.

Just below the number 793 is a red handstamp stating “NO RECORD. A.P.O. 727,” apparently another attempt to locate Appleton. APO 727 was established Feb. 4, 1918, and served the 41st Division at St. Aignan, Loir-et-Cher, France. Private Appleton wasn’t there, either. Another red handstamp, with the date of Sept. 3, 1918, is below and to the right of the APO 727 marking, probably applied by the same person who applied that handstamp.

Finally, there are three lines of handwritten text at the top of the cover near the postage stamp. These read, “Received/St. Jacques/Oct 12/18.” Was this where Private Appleton was finally located? According to the Summary of Information Vol. 3, U.S. Army American Expeditionary Forces General Staff, it was reported on Oct. 21, 1918, at 11 a.m., “that north of the Oise [River, in France] the night was marked by great activity of the enemy’s artillery. Between the Oise and the Serre a hostile raid east of Catillon du Temple was without result. On the Serre front we have again made progress. Our troops have reached the railway northeast of Assis-sur-Serre as well as the farm of St. Jacques, northwest of Chalandry.”

But did Private Appleton ever receive the letter at the St. Jacques farm? I hope so, because there was a dandy poem inside the cover that would have made him laugh.

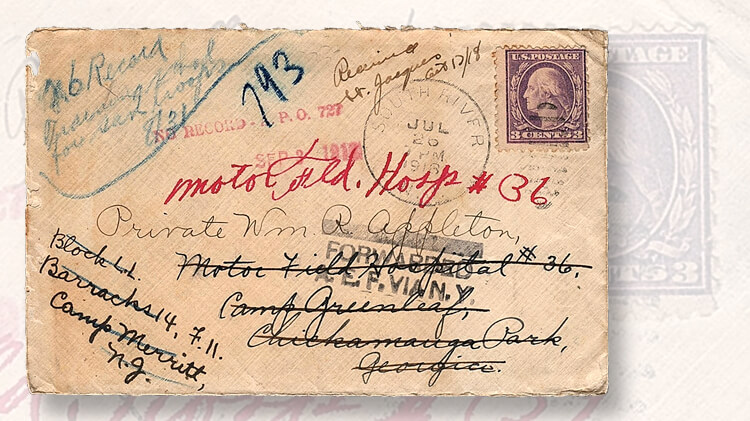

An even trickier cover is shown in the second illustration. This is a stampless folded letter sent from Germany to Cincinnati (misspelled “Cininaty”), Ohio, in 1851, getting there via trans-Atlantic mail. The letter itself is in German, three full pages of quite small cursive handwriting that looks interesting but is difficult to read.

For a collector, however, the most fascinating aspect of this folded letter is the copious collection of postmarks that pepper the front and back. Some of the markings are quite perplexing to discern. Fortunately, there is a wonderful website, Retro Reveal that can help. It is free, and here is how it works. First, you must make a digital scan of your cover. Then follow the directions on the Retro Reveal website to download the cover image onto Retro Reveal. Your image will be displayed on the computer screen. Click on it, and Retro Reveal will apply several filters, which will amplify and clarify elements of the images.

Page through all of the filtered images to find the ones that are most helpful. You can save the images that Retro Reveal provides. The third illustration shows one of the Retro Reveal images of the German cover in the previous illustration. There is a very clear double-circle postmark from Paris dated “10 Fevr 51” (Feb. 10, 1851). That was easy.

Just below the Paris postmark is a straightline “KANDERN,” which is a town in southwest Germany in the state of Baden-Wurttemberg. The straightline marking points directly to another double-circle postmark, “BADE[N],” dated “8 FEVE 51” (Feb. 8, 1851). The bottom of that postmark is partially missing and the text that is there is smudged. Retro Reveal made some letters slightly clearer to the point that “BADE BADE” was just about visible. If indeed it reads “BADEN-BADEN,” that makes a handwritten instruction on the cover more understandable.

Look just below the second line of the address, the line that begins “care of.” On the far left you will see “via France” handwritten, to indicate that the sender, who must have posted the letter from Baden-Baden on 8 Feb. 1851, wanted the letter to go through France to get to the United States. It was probably the fastest way, since Baden-Baden is near the border of France.

To the right of the Baden postmark is another round postal marking that is fuzzy. Retro Reveal cleared it up slightly, enough that the letters “P.D.” seemed to appear. According to Understanding Transatlantic Mail by Richard F. Winter, the “P.D.” handstamp means that the letter was paid to the destination.

Below the last line of the address, two more handstamps appear. The one on the left is a boxed “P.” Winter’s book identifies this marking as originating from Baden’s Kehl exchange office, to indicate the letter was prepaid. Right next to it is a diamond-shaped handstamp with a “7” at the top and the initials “A.E.” and “J.F.” The A.E. stands for “Affranchie a l’Entranger,” and the J.F. for “Jusqu’a la Frontiere.” In English, the two lines together mean “to the border” and “paid only to the [exiting French] frontier.”

Below the boxed “P.” and diamond-shaped “A.E./J.P.” handstamps is an oblong box containing two lines of type: “E.B. 7 Feb 51” and “Curs 1.” These indicate the date the letter was handled and the postal crew that marked the letter.

Below the oblong box is another extremely difficult to read double-circle postmark. Retro Reveal even had a difficult time with it, but a very precise magnifier enabled the identification of a few letters, enough to work out that it was postmarked “Bureau Maritime Havre/10 [or perhaps 16] Fevr 51.” The cover was put on board a ship from Havre and, if you look at the largest postmark, you can see that it arrived in New York, via ship, on March 20. The “12 cts.” at the bottom of the postmark indicates the postage due to be paid by the recipient in Cincinnati: 2¢ for the incoming ship fee and 10¢ for the inland fee.

As you look at the oblong box and the Bureau Maritime postmark, you may notice some lightly handwritten red pencil lines in the background. These are likely to be the postal fee(s) for the cover going from Baden-Baden to the United States. Retro Reveal did a fantastic job of making the red pencil lines visible, as shown in the last illustration, as two sets of numbers: “25” and “27.”

These have been examples of two types of covers that are challenging. Mail sent to military personnel during wartime is likely to be forwarded multiple times, and tracing the journey through cover markings takes time and effort.

Trans-Atlantic mail is even more difficult because of the involvement of numerous countries, languages, and, often, postal conventions that altered rates and routes.

The two-volume work Understanding Transatlantic Mail by Richard F. Winter is extremely helpful, but working through the process on a particular cover requires patience and concentration.

Nevertheless, you will find it worth the effort to solve the mystery of your covers. You will learn more history and gain philatelic skills, and you might even find a gem among those difficult covers.

Related articles:

Identifying Asian stamps if you don’t know the language: Stamp Collecting Basics

Stamps without a country name present a special identity challenge: Stamp Collecting Basics

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers