Auctions

Registered 1967 cover bearing Qatar Sheik Ahmad set tops $1,100 in eBay auction

By Charles Snee

On Feb. 24, 1966, Qatar issued a set of 12 circular, gold-foil stamps depicting Sheik Ahmad bin Ali al Thani.

A complete set of 12 is valued in the 2016 Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue at $172.25 in mint never-hinged condition, and at $42.05 in used condition.

Both of these set totals (as well as the individual unused and used values) are italicized, meaning that limited market data is available to the Scott editors.

In fact, the Scott Standard catalog provides a cautionary note at the beginning of the Qatar listings: “The market for Qatar stamps is extremely volatile, and dealer stocks are quite limited. All values for this country are tentative.”

This information is important, because it helps explain the keen attention recently paid during an online auction to a registered cover, shown nearby, that was mailed in 1967 from Doha, Qatar, to Beirut, Lebanon. The envelope is neatly franked with a complete set of the Sheik Ahmad gold-foil stamps (Scott 99-99L).

Each of the 12 stamps bears a faint oval “REGISTERED DOHA QATAR” postmark. A clear strike of this same marking on the back of the cover (not shown) shows that the cover was mailed from Doha March 30, 1967.

In addition, the Doha registry postmark faintly ties nine of the 12 stamps to the approximately 11-inch-by-8½-inch brown envelope.

An indistinct receiver postmark on the back confirms that the addressee received the cover April 3, four days after it was mailed.

Postal history dealer (and former Linn’s senior editor) Rob Haeseler, who operates under the eBay moniker “bloodlesscoup,” offered this cover during a seven-day eBay auction that closed Oct. 24.

Haeseler started the auction with an opening bid of $195.

A week later, after the dust had settled, the cover sold for an eye-popping $1,190.95. This realization includes a $49.95 shipping fee assessed by Haeseler.

Although Haeseler would not disclose where or when he found the cover, he did provide some valuable insights about the bidders who vied to acquire the colorfully festooned cover.

First, he said, a total of nine bidders from just three countries — Qatar, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates — placed a total of 31 bids during the course of the week-long auction.

The winning bidder jumped into the fray rather late in the game, placing an initial bid three hours before the sale ended. At that point, the high bid stood at $1,000.

Then, just 10 seconds before the close, the eventual winner placed an undisclosed snipe bid.

Five seconds later, the underbidder launched his bid of $1,116, which was not enough to eclipse the winner’s bid.

Adding in eBay’s $25 increment for one advance over the second-highest bidder (standard procedure during an auction) brought the cyber-hammer price to $1,141.

Some might dismiss the price paid for this cover as a severe case of overzealousness for what, at first glance, looks like a blatant philatelic use of some shiny stamps from a country that most people couldn’t locate on a map.

(For the geographically inclined, Qatar is a peninsula bordering eastern Saudi Arabia that juts into the Persian Gulf. Its nearby neighbors include Bahrain to the northwest and the United Arab Emirates to the southeast.)

Nonetheless, this cover is an important artifact of its time. And that is one reason why the new owner, who in all probability lives in the Middle East, paid almost $1,200 for it.

Both the nameless sender and recipient A.G. Camileri worked for the National Cash Register Co., which lends credibility to the commercial nature of this cover, despite its being franked with a complete set of stamps that some collectors dismiss as gimmicky baubles.

Haeseler told Linn’s that the Sheik Ahmad and other similar stamps of the time were “speculative and contributed to the image of sand-dune Arab Gulf states and former African colonies hawking wallpaper and tinsel postage to prey on the often modest means of stamp collectors.”

The term “sand dunes” is a pejorative that many collectors at the time attached to the stamps of certain countries with Arab connections and poorly understood postal administrations/systems, such as Ajman and Fujeira.

It turns out that the perception of the speculative nature of Qatar stamps dates back to at least the mid-1960s, not long after the Qatar government assumed control of its postal administration in March 1963.

According to a Feb. 22, 1965, report in Linn’s by Edgar Lewy, Qatar officials “were determined to ensure an equitable distribution of stamps to all parties interested in acquiring them,” and that they wished “to prevent speculation at collectors’ expense.”

A “Philatelic Post Office Agency” was set up, and Lewy described this entity as “the first step in implementing a policy which can be described as combining philatelic interest with a fair chance for all collectors” to get the stamps they desired directly from Qatar.

A half century later, it hasn’t quite turned out that way.

In 1962, the American Philatelic Society launched its so-called “Black Blot” program against what the society deemed to be philatelically excessive and/or speculative issues.

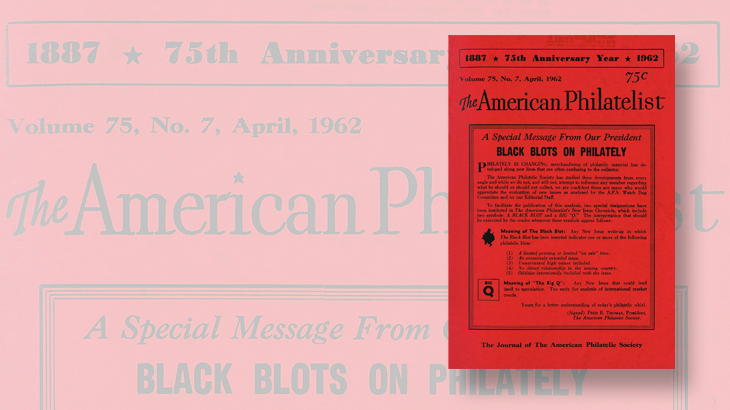

“BLACK BLOTS ON PHILATELY” proclaimed the headline on the front cover of the April 1962 issue of the American Philatelist, followed by a statement from APS president Fred B. Thomas.

To promote the program, Thomas declared that “we are confident there are many who would appreciate the evaluation of new issues” by a group with an Orwellian sounding title: the “A.P.S. Watch Dog Committee.”

Thomas presented five criteria, or “blots,” one or more of which would earn a stamp a black smudge symbol next to its listing in the American Philatelist’s New Issue Chronicle:

“A limited printing or limited ‘on sale’ time; an excessively extended issue; unwarranted high values included; no direct relationship to the issuing country; oddities intentionally included with the issue.”

Paired with the Black Blot was the so-called “Big Q” that would appear in the New Issue Chronicle next to any new-issue listing “that could lend itself to speculation.”

Although the APS formalized its Black Blot program in 1962, its roots go back to 1954, when the APS began an organized campaign against the then-nascent burgeoning of speculative postal issues and other items masquerading as regular postage.

In that same April 1962 issue of the American Philatelist, Robert W. Murch, chairman of the APS new issues committee, trumpeted that since 1955 the APS “has continued to publicize the existence of this type of ‘philatelic wallpaper.’ …”

“… [T]oday’s New Issues of the World should be carefully considered if future financial disappointment is to be avoided,” Murch opined in a boxed note to his Watchdog Committee report No. 8.

“A collector’s best friend in 1962 is a reliable dealer handling legitimately issued stamps at a fair mark-up over face value. If this policy is followed speculation will cease.”

Ken Lawrence, a noted expert of the so-called Sand Dunes stamps, told Linn’s that the Black Blot program was never formally rescinded:

“American Philatelist editor Dick Sine wrote in July 1978 that ‘The Current New Issues Committee, conceding that there are negative implications to the program, is searching for a way to preserve the thrust of the Black Blot program in a more positive way.’ After that it faded from view.”

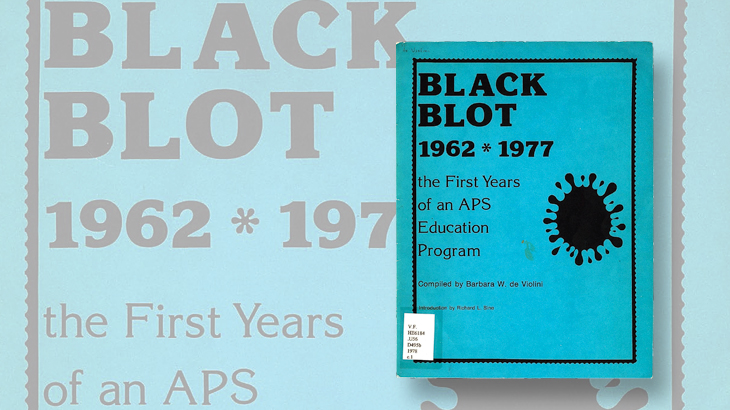

In that same year, the APS published a 23-page handbook titled, Black Blot 1962 * 1977 the First Years of an APS Education Program.

Black Blot lists alphabetically by country and Scott number all of the APS black-blotted stamps. Stamps included in the Scott catalog “For the Record” listings also were assigned a black blot, but these stamps are not listed in Black Blot.

While five 1964-72 issues from Qatar are listed in Black Blot, the 1966 Sheik Ahmad set of 12 is not among them.

Lawrence also opined that the Black Blot program was not without political motivation.

“Black Blot was especially obsessed with ‘commie’ and Arab issues, and those of newly independent small former colonies,” Lawrence said.

He further stated that “the largest number of explicitly enumerated banned stamps” were for “East German issues.”

Also banned “without exception” were stamps “issued by Ajman, Anguilla, Barbuda, Equatorial Guinea, Fujeira, Grenadines of Grenada and Saint Vincent, Mahra Sultanate, Manama, Quaiti State of Hadhramaut, Ras al Khaima, Sharjah, Umm al Qiwain, and Yemen Kingdom, as though those countries had no postal needs at all, while condemning only one Monaco set and none of the British regional issues.

“Black-Blotted U.S. stamps included the 1962 Hammarskjold invert reprint, which largely reflected APS members’ opinions; and the 1973 Postal People, 1974 Universal Postal Union, 1976 State Flags, and 1976 Bicentennial souvenir sheets, which probably overstepped their implied mandate and hastened the end.”

Echoes of the Black Blot program can be seen today in the Scott catalog listing policy, which is spelled out in the introduction. For example, Scott does not list stamps that are deemed to be “controlled issues and/or are intended for speculation.”

If you haven’t read the Scott catalog listing policy, take a few minutes and do so. A basic familiarity with this important section will help you better understand why some stamps do not receive Scott numbers.

All of which brings us back to the eye-catching 1967 registered cover from Qatar.

A solid four-figure realization for an item that attracted 31 bids from nine different collectors is a positive indicator that stamps and postal history from the Middle East during this time period, regardless of their speculative nature, are undergoing a rehabilitation.

This development, all things considered, bodes well for the hobby and its future in the digital age.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers