Auctions

Slew of eye-catching U.S. stamp rarities sold during March 1-2 Siegel sale

Auction Roundup — By Matthew Healey, New York Correspondent

Siegel’s sale of United States stamps on March 1-2 offered a plethora of eye candy — beautiful designs, rich colors, and large margins — as well as some interesting lesser-seen items.

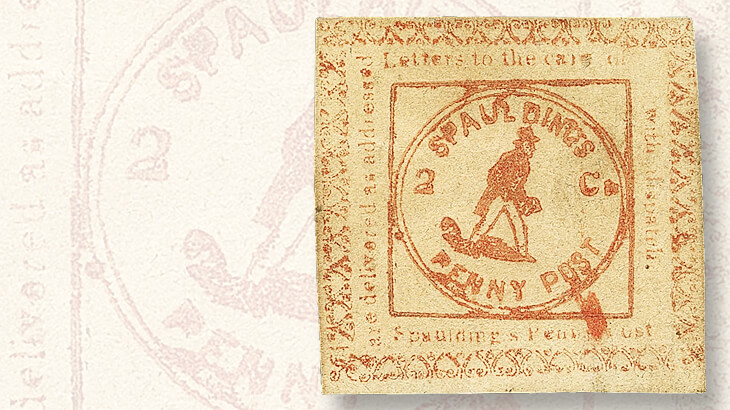

Among the latter category was a very rare local post stamp from Buffalo, New York, issued by a firm called Spaulding’s Penny Post.

Door-to-door mail delivery in America was limited until the 1860s, so local firms filled in the gaps. Private city posts would charge 1¢ to pick up letters and take them to the post office, or 2¢ to deliver them to another address.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Dozens of firms issued their own postage labels for these purposes, many of which are now rare.

Spaulding’s issued a crudely printed label showing a mailman surrounded by the name of the firm, in two versions: a simple squared circle and a fancier version with an ornamental frame and the wording “Letters to the care of / Spaulding’s Penny Post / are delivered as addressed / with dispatch.”

This latter version was only discovered a century later, by a philatelist named Frieda Bulger, on a cover that has never been publicly offered for sale.

The unused example in the Siegel sale, which is the one depicted in the Scott catalog, first surfaced in the 1970s. It sold for $25,960.

One of the vicarious pleasures of following high-end stamp auctions, even knowing one could never afford any of them, comes from the extraordinary quality and beauty on display.

For more than a decade, using numerical grades to rate stamps based on their centering, condition, and overall appearance has been an accepted part of U.S. philately.

Grading is credited by many with helping the hobby, because it removes a major element of subjective uncertainty in judging a given stamp.

The paucity of graded stamps at the top end of the scale can lead to a competitive frenzy that drives prices for otherwise common stamps to astronomical levels, generating considerable excitement.

Among the superlative items in Siegel’s sale was a magnificent unused example of the 10¢ Washington of 1855, which is pictured in the image below. Philatelists recognize several types of this classic design, based on how much of the top and bottom framelines are present, absent or recut, and this example belonged to type II, with the top almost complete (Scott 14).

Boasting huge margins “which frame the design like a small die proof,” rich green color and original gum with only a light hinge mark, this virtually unmatched example was judged to grade superb 98 (out of 100); it brought $34,220.

Boasting huge margins “which frame the design like a small die proof,” rich green color and original gum with only a light hinge mark, this virtually unmatched example was judged to grade superb 98 (out of 100); it brought $34,220.

By comparison, an example that grades merely very fine is valued at $5,000 in the Scott U.S. Specialized catalog.

It’s easy to see how imperforate stamps, which were cut apart by hand using scissors or pocket knives, could vary in size. But why are perforated stamps also variable? The answer is not so much that early perforating equipment was imprecise, but that engraved stamps had to be printed on dampened paper, which dried and shrank unevenly, making it hard for the rows of perforating holes to be perfectly positioned on all four sides of a stamp. Examples where this did happen tend to be rare, with commensurate prices.

A 90¢ Oliver Hazard Perry stamp, printed by the American Bank Note Co. in 1879 (Scott 191), was graded extremely fine-superb 95 by the Professional Stamp Experts firm, thanks to its generous, even margins and overall freshness.

With its rich, delicate rose shade, Siegel called it “one of the finest mint, never-hinged examples” in existence. Indeed, only one other example has reached its grade, with none exceeding it. The stamp went for $25,960.

Exceptional examples of otherwise common stamps abounded throughout the sale. A gem 100 “jumbo” example of the 5¢ Ulysses S. Grant from the final Banknote issue of 1890 (Scott 223) boasts margins that are not just evenly balanced but exceptionally large, as well as never-hinged gum — in other words, an essentially perfect stamp.

One other example of Scott 223 shares this distinction, but according to Siegel, “there are no other mint N.H. stamps graded 100J among all the denominations of the 1890-93 issue.” It sold for $18,880.

Early commemoratives in outstanding condition were similarly represented.

A 10¢ Fast Ocean Navigation stamp from the 1901 Pan-American Exposition series (Scott 299) was graded superb 98 jumbo by PSE. “The highest grade awarded and the only example to achieve it,” according to Siegel, it brought $30,680. It is pictured below.

A 1907 5¢ Jamestown (Scott 330), likewise graded superb 98 jumbo, is considered even more of a condition rarity: Well-centered examples of that issue can be notoriously hard to locate, thanks to the tight spacing between stamps. The example in the Siegel sale, likewise unique in its grade, went for a whopping $38,350.

A 1907 5¢ Jamestown (Scott 330), likewise graded superb 98 jumbo, is considered even more of a condition rarity: Well-centered examples of that issue can be notoriously hard to locate, thanks to the tight spacing between stamps. The example in the Siegel sale, likewise unique in its grade, went for a whopping $38,350.

A perfectly centered, never-hinged 6¢ orange Curtiss Jenny airmail stamp of 1918 (Scott C1), one of just a couple graded gem 100 by PSE, sold for $11,800.

Even the humblest stamps, highly graded, made their mark in Siegel’s auction.

A used 4¢ coil stamp of the Washington-Franklin definitive series of 1908-20 (Scott 495), which normally catalogs $7 in the grade of very fine, was offered with wide margins, near-perfect centering, and an “unobtrusive” cancel. Graded superb 98, again the only one to gain this lofty award, it fetched $442.50.

Other notable items in the sale included a rare, early government-produced coil pair.

At the beginning of the 20th century, numerous private firms and the U.S. Post Office Department raced to find a workable method of automating the sale of stamps to the public.

Vending machines that could be loaded with rolls, or coils, of stamps appeared promising, and in 1908, with no fanfare, the post office issued a test version of its 1903 1¢ Franklin stamp.

This coil was produced by perforating sheets of 400 in one direction only, then cutting them into strips of 20 and pasting the strips together.

The experiment, which most collectors and dealers at the time were unaware of, lasted less than a year. It’s unclear how many were produced, but Siegel’s census of surviving examples includes just 12 pairs and a single, all unused.

The pair offered March 1, with small faults but otherwise attractive, sold for $94,400. See it in the image below.

New discoveries are one of the things that keep the stamp hobby exciting, and the 2017 Scott U.S. Specialized catalog includes a newly listed stamp: the 2¢ Washington-Franklin definitive, type I, in a distinct dark-red shade known as lake, emanating from a booklet (Scott 499i).

New discoveries are one of the things that keep the stamp hobby exciting, and the 2017 Scott U.S. Specialized catalog includes a newly listed stamp: the 2¢ Washington-Franklin definitive, type I, in a distinct dark-red shade known as lake, emanating from a booklet (Scott 499i).

(The 2¢ types of the Washington-Franklins are distinguished by details of the engraving, such as shading lines on the scrolls and the button of Washington’s toga.)

The stamp offered in the Siegel sale is the “discovery example” of this new listing, and so far the only 2¢ Washington-Franklin known with this combination of attributes. Certified last year by the Philatelic Foundation, it sold for $2,242.

Siegel’s sale posed an unusual question: Would anybody pay $1,000 for a stamp that had been torn in half? The answer turned out to be yes.

The first series of U.S. postage due stamps was printed by the American Bank Note Co. in 1879. That same year, the stamps were specially reprinted on soft, porous paper. The reprints are scarce, with fewer than 250 of the 5¢ (Scott J11) sold to the public.

At some point, one example of the 5¢ had the sorry misfortune of being torn in two. Rejoined, the “otherwise fine” stamp nevertheless fetched $1,180 — a testament to its scarcity.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers

-

World Stamps

Oct 5, 2024, 1 PMCanada Post continues Truth and Reconciliation series