Auctions

Classic 1875 reissue of classic 1862 stamp highlights Harmer-Schau sale

By Matthew Healey, New York Correspondent

In preparation for the Centennial celebrations in 1876, the United States Post Office Department decided to reissue all postage stamps issued up to that date.

These “special printings” were done from the original plates and in colors close to the originals, except for the 1847 stamps, whose plates and dies could not be located and had to be reproduced from scratch.

The special printings typically can be distinguished from the original stamps by the harder, whiter paper on which they were printed, and in some cases by subtle differences in the shade of ink.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Philately was not yet a widespread hobby at the time. John Walter Scott had published his first price list less than a decade before, and many collectors did not appreciate the collectability of the special printings. Though most of them sold poorly, the Post Office Department did keep precise records of the quantities, which in some cases was fewer than a handful.

Because many of the special printings were valid for postage, they are all listed in the main body of the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers, interspersed with the conventional issues of the era. Spaces for the special printings are included in many stamp albums, although thanks to their scarcity, they generally sit empty in the vast majority of U.S. collections.

Among the U.S. items in the Jan. 13-15 sale held by Harmer-Schau Auction Galleries of Petaluma, Calif., in conjunction with the Orcoexpo stamp show, was a crisp, well-centered example of the special printing of the 24¢ Washington stamp from the 1861-66 definitive series (Scott 109). It was described by the auction firm as “very fresh on face” and “one of the nicest looking … we have seen,” albeit with somewhat toned gum.

The reprint, in an almost brownish shade of dark violet, beautifully shows off the extravagant machine-turned background and ornate stars and scrollwork of the frame that served as a built-in safeguard against forgery.

Just 346 examples of this special-printing stamp were sold in the months after issue, with the rest withdrawn and eventually destroyed.

The example in the Harmer-Schau sale brought $4,887.50, including the 15 percent buyer’s premium added by the firm to all lots.

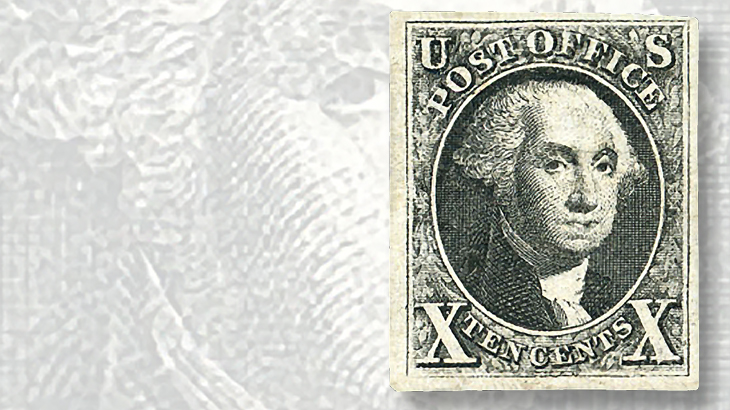

The 1875 reproductions of the 1847 5¢ Franklin and 10¢ Washington stamps that made up the first U.S. stamp issue (Scott 3-4) were somewhat more popular at the time and, although not valid for postage, they sold well and are not uncommon today.

They can also be found as plate proofs on card (Scott 3P4-4P4), which catalog about one-fifth as much as the actual stamps. Two sets of these proofs were in the Harmer-Schau sale; one brought $172.50, while the other brought $241.50.

The U.S. government weren’t the only ones making copies of the 1847 issue. The famous Italian forger Jean de Sperati tried his hand, too, with pretty convincing results. His forgeries tend to be just as collectible as the real thing: Sperati’s version of the 1847 10¢, certified a fake by the American Philatelic Society, sold for $460.

Those looking for an authentic 1847 10¢ in the sale were not disappointed. A number of handsome, used examples were offered, sporting a variety of colorful cancels. One with a partial blue town cancel and four nice margins sold for $661.25.

Turning to the 20th century, a rare used pair of an imperforate 5¢ Lincoln stamp from the 1908 definitive series (Scott 315) with a clean, wavy-line cancel was featured on the front page of Linn’s issue of Jan. 9 with a preview of the sale.

Only a few of these imperforate varieties were issued, mostly to firms experimenting with coil-making machines. A few hundred examples reached members of the Detroit Philatelic Society, and it is thought that this is where the known used examples originated. The pair went for $4,887.50.

From the back of the book, a $1 proprietary revenue stamp of 1874, printed on green paper (Scott RB9b), is believed to be one of just seven surviving used examples. Remarkably, two of these examples appeared in the sale. One, with some toning and a minor tear but a very light handstamp cancel, sold for $4,600 while the other, with barely visible faults and a somewhat heavier handstamp-and-manuscript cancel, brought $4,025.

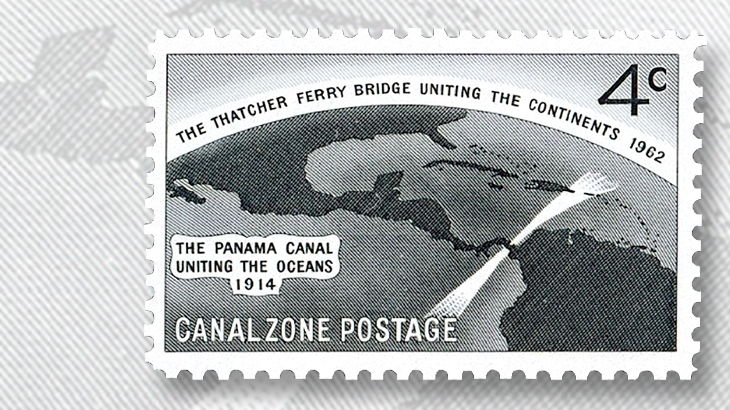

Turning to U.S. possessions, Harmer-Schau offered an example of a striking missing-color error from the Canal Zone.

One sheet of the 1962 4¢ commemorative for the Thatcher Ferry Bridge escaped the printers without its silver intaglio ink, resulting in … no bridge. The famous error (Scott 157a), of which just 50 are known, sold for $6,900.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers