Auctions

Vertical strip of Washington-Franklin stamps tops $165K at Siegel auction

Auction Roundup — By Matthew Healey, New York Correspondent

When the United States Post Office Department decided, early in 1909, to try and solve its stamp-production problems by experimenting with a rag-based paper, it opened an esoteric but fascinating chapter in United States philately.

That chapter is now told, with more information than ever before, in the introduction to Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries’ catalog for the Barry K. Schwartz collection of the U.S. “bluish paper” issues of 1909, sold in New York Feb. 28.

The regular stamp paper used at that time posed two difficulties. After being dampened for printing, the paper would shrink as it dried, wreaking havoc on perforation alignment.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Then, as the gum on the back of the stamps dried, it would cause the sheets to curl and split. Some 9 percent of stamp production ended up being unsuitable for use — an expensive headache for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, D.C.

A paper with 30 percent to 35 percent rag content was tried, in the hope it would prove more stable. Although today this paper appears more gray than blue, contemporary descriptions likened its appearance to skim milk, and the “bluish” nickname stuck.

Several thousand sheets of then-current 1¢ and 2¢ stamps were printed on bluish paper: the Washington-Franklin definitives (Scott 357-358) and the 2¢ Lincoln centennial commemorative (369).

Today, these regularly issued bluish-paper varieties are worth a nice premium, especially with contemporaneous postmarks, though they are by no means rare.

Unfortunately, the experimental paper didn’t solve the production problems, and its use was halted. The remaining stock was set aside.

Enter Arthur M. Travers, the acting third assistant postmaster general, whose career and reputation would soon be ruined by a pair of fateful decisions.

In late January 1909, Travers ordered the BEP to use the leftover bluish paper to run off some extra sheets, not just of the stamps already printed, but also of the Washington-Franklin series from 3¢ to 15¢ — 11 denominations in all. Some 10 sheets to 13 sheets of 400 stamps each were produced, divided as usual into panes of 100.

According to Siegel’s catalog, which lays out the definitive story of the bluish paper issue in a most accessible way, these specially printed sheets were meant “for the Department’s files” and for the “Museum Collection.”

Four panes of each denomination were delivered to Travers. The rest, except for the 4¢ and 8¢ denominations, were sent out (perhaps inadvertently) to post offices around the country.

Travers put two sets of panes into the archives, and then succumbed to temptation.

On March 6, 1911, Travers was arrested and indicted for embezzlement and conspiracy. He had been discovered selling a set of panes of his bluish-paper special printings, including the otherwise unobtainable 4¢ and 8¢ stamps, to a prominent Philadelphia-based stamp dealer named Joseph A. Steinmetz.

Travers pled no contest, was fined $1,500 (the amount of his purported bribe) and lost his job.

Two years later, the curator of the National Museum stamp collection was authorized to trade away additional bluish-paper stamps to fill holes in the museum’s collection.

This would prove to be the only other source for the 4¢ and 8¢ stamps on bluish paper, which today are among the rarest U.S. 20th century stamps.

Barry Schwartz began his collection of this issue in 1977, when he acquired some rare plate blocks in Siegel’s sale of the collection of W. Parsons Todd, who had bought some of the original dispersals of bluish-paper stamps more than six decades earlier.

Over the years, Schwartz built his collection up to the point where Siegel called it “the finest and most comprehensive … ever formed” of the bluish-paper stamps.

The pieces de resistance remain the plate-number multiples, which in several cases are unique outside of government archives.

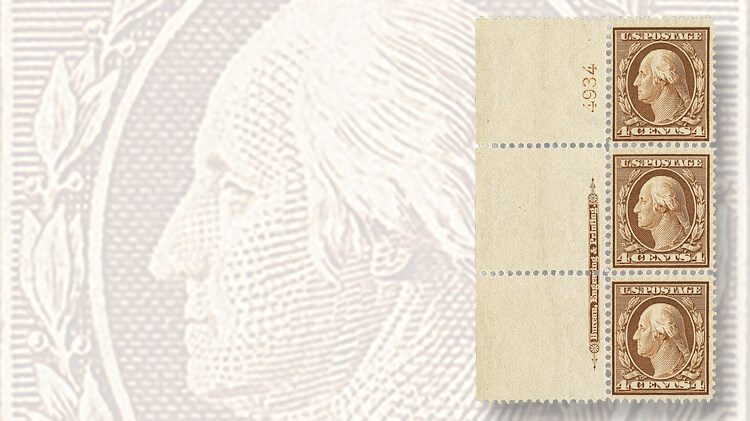

A vertical strip of three of the 4¢ (Scott 360) is “the only imprint and plate number strip … in private hands,” according to the Siegel catalog description. (A single with the number in the top margin, from the same pane, also is known.)

Although four different plates were used simultaneously to print the 11 sheets of the 4¢ on bluish paper, only one other pane of 100 is known. It bears the same plate number and is in the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum.

The rest of the 4,400 stamps were presumably lost in the archives or destroyed. There are no known full plate blocks of the 4¢ or 8¢ on bluish paper.

The strip sold for $165,200, including the 18 percent buyer’s premium charged by Siegel on all lots.

A block of four of the 4¢ is thought to be one of very few blocks surviving, as most had been broken up for singles by the 1960s. It fetched $88,500.

A horizontal plate-and-imprint strip of the 8¢ (Scott 363), the only such surviving intact strip, went for the same amount, while a rejoined vertical strip brought $70,800.

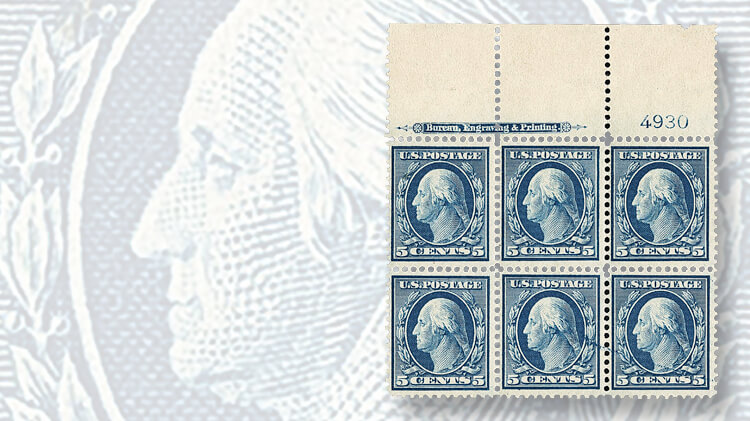

The plate block of six of the 5¢ (Scott 361) is believed to be the only surviving one outside of Post Office archives. At least two other plate blocks have been broken up into singles. Schwartz’s block changed hands for $141,600.

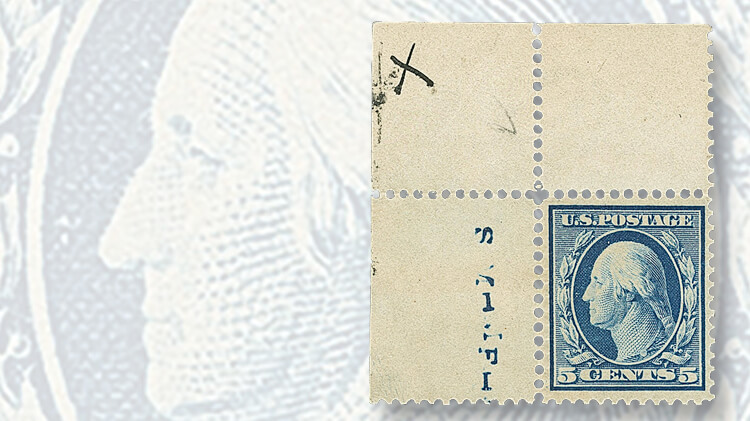

An upper-left margin single of the 5¢ bore an inconspicuous but significant marking: a penned “x” in the corner of the selvage. This telltale notation was made by the printers to indicate that the sheet was on the experimental paper. The only single of the 5¢ to retain its marked margin, it sold for $7,080.

The rest of the 55 lots from the Schwartz collection covered the remaining denominations, including multiples, used examples and postal history.

A used block of four of the 13¢ (Scott 365) was from a quantity sent to Saginaw, Mich., where it received a light, oval cancel. The only known used plate-number multiple of the bluish-paper series, the block brought $17,700.

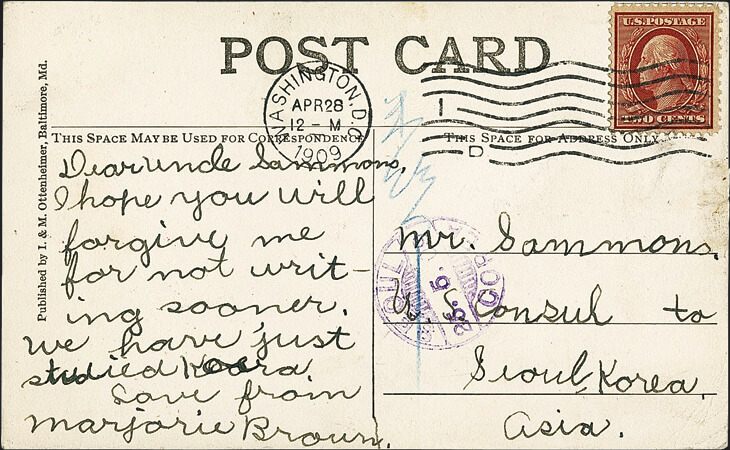

A cover addressed to an American advisor to the king of Siam (modern Thailand) with its 5¢ bluish-paper stamp removed but reunited, went for $30,680, while a charming postcard addressed in a child’s hand to Korea, bearing one of the regularly printed 2¢ stamps (Scott 358), crossed the block for $826.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers

-

World Stamps

Oct 5, 2024, 1 PMCanada Post continues Truth and Reconciliation series