POSTAL UPDATES

insights

Preserving the lost art of penmanship to understand old letters

By Janet Klug

A recent magazine article asked readers to comment on whether or not schools should teach children cursive handwriting.

The opinions expressed by readers made good cases, both pro and con.Many school districts eliminated cursive handwriting instruction as part of their curricula several years ago, so it is no surprise that a large percentage of young people print rather than write in cursive.

On the side of eliminating cursive handwriting instruction, one reader postulated it was an art form and wastes valuable teaching time needed for core subjects. Computers are used for everything, including classwork, therefore cursive is no longer needed.

Those favoring cursive being taught compared its relevance to the use of calculators in schools: children now cannot do simple math without them. Texting has reduced spelling to acronyms, and, if there is a power failure, children will no longer be able to add, read or write.

My concern is that at some point, students will not know how to read the cursive handwriting that exists in many places, including the Constitution of the United States of America, and in old correspondence.

Those of us of a certain age learned cursive writing in elementary school, probably in the third grade. We practiced it and were graded on our penmanship. In fact, my fellow classmates and I were required to use fountain pens until we got to high school.

We were taught the Palmer method, a simplified and less beautiful style of writing that replaced the Spencerian method in the 1920s. Many of the most beautiful stampless covers are addressed and written by those who practiced the Spencerian method of penmanship that flourished, quite literally, from the middle of the 19th century until Palmer's method replaced it in schools.

The small lady's cover embossed with the writer's initial "E" for "Elizabeth," shown in Figure 1, provides an example of Spencerian cursive. The letter contained within is dated Aug. 4, 1873, and the letter is signed "Bessie," a nickname for Elizabeth. Bessie practiced Spencerian cursive.

In the days before typewriters, telegraphs and telephones, business record keeping and communications were handwritten. The handwriting had to be clear and precise so that orders were filled properly and records were not open to misinterpretation.

Employers put great stock in hiring clerks who could write a good hand. Business colleges taught courses in penmanship because it was a vital skill for a worker to have.

Figure 2 illustrates a cover that shows Spencerian script both on the advertising element at the top of the cover and in the handwritten address. It was sent from the Spencerian Business College in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1890. Besides teaching business courses, as this cover advertised, the school offered "A complete school of penmanship."

The swooping curlicues of Spencerian script fell out of fashion in the late 19th century when Austin Palmer developed a style of handwriting that was more easily learned, although in my own case, I still remember spending hours filling sheets full of repetitive strokes.

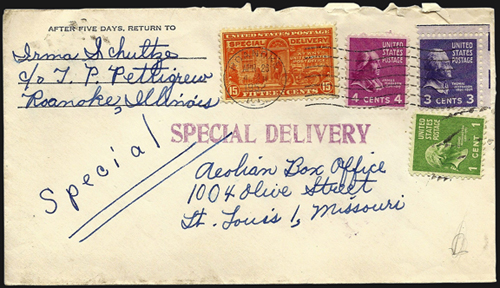

Figure 3 shows an example of Palmer cursive in the addresses on a special delivery cover mailed from Roanoke, Ill., to St. Louis, Mo., in 1952.

Today, some schools are teaching a modified type of manuscript writing called D'Nelian that is based on printed letters slanted like italics. Eventually, this is supposed to morph into D'Nelian cursive that will somewhat resemble the old Palmer method.

Those who love beautiful handwriting might consider collecting stamps that illustrate cursive writing.

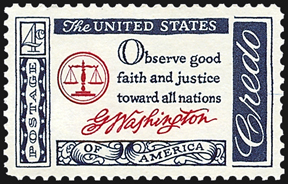

United States stamps are rife with examples, such as the America Credo series (Scott 1139-44) issued in 1960 and 1961.

These 4¢ stamps give a brief quotation and then show a model of the signature of the person whose credo it represents: George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Francis Scott Key, Abraham Lincoln and Patrick Henry. The 4¢ George Washington's Credo stamp (Scott 1139) is shown in Figure 4.

The signatures are not exact replicas. George Washington's signature was modernized, because in his day Washington signed with the "s" shaped very much like an "f," so that to modern eyes the father of our country's signature looks like "Wafhington."

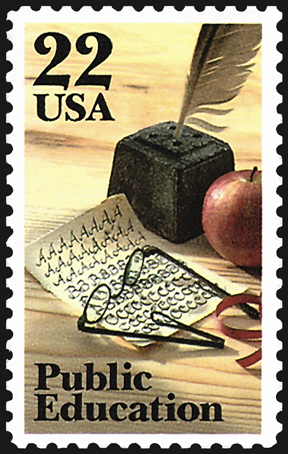

Figure 5 depicts the 1985 22¢ Public Education stamp (Scott 2159). The design shows a practice sheet full of script that looks somewhat like Spencerian, as well as the ink and quill pen used to create it.

A year later, the U.S. Postal Service issued a set of four souvenir sheets (Scott 2216-19) depicting all of the presidents from Washington to Lyndon Johnson, with replicas of their signatures above their heads. This time Washington's signature is shown as he wrote it.

Old letters and documents are worth keeping, reading and understanding.

If we lose the ability to read cursive writing, how will we fully appreciate the history we care for in our collections?

For help in understanding old documents, visit the Archiving Early America web site at www.earlyamerica.com.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers