POSTAL UPDATES

insights

Stamps without a country name present a special identity challenge: Stamp Collecting Basics

By Janet Klug

It’s surprising how many of the world’s postal administrations have issued stamps without the country’s name. So many, in fact, that it is taking more than one of these columns to cover all of them. The first in this series was published in the March 21 issue of Linn’s.

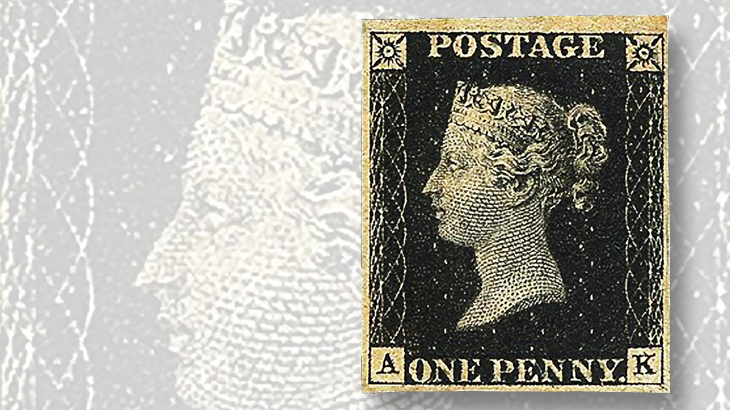

Most collectors understand that Great Britain’s stamps are identified by having a likeness of the reigning monarch, and without the name of the country.

This tradition began with the world’s first adhesive postage stamp, which was issued in May 1840 and bore a portrait of Queen Victoria. Subsequent British stamps have carried the identifying images of King Edward VII, George V, Edward VIII, George VI and Elizabeth II.

As it turned out, many European nations followed Great Britain’s lead and issued stamps without a country name. Savvy collectors seeking to identify origins of stamp issues have to learn to recognize images of people and symbols, words and other clues that often represent a certain country, and/or delve into stamp-identification books.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

A stamp issued by Armenia in 1921 (Scott 280) is illustrated here, and noting the star, hammer and sickle, you might think the stamp is from Russia. You would not be far wrong.

The Red Army invaded Armenia in late 1920, and the nation’s independence ended in July 1921. Scott 280 is part of a set of 17 stamps issued for the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. The Soviet symbols on the new stamps make the political situation very clear.

In 1923, Armenia began using Trans-Caucasian Federation stamps. After the Soviet Union disbanded in 1991, Armenia became independent and began issuing stamps inscribed “Armenia.”

Many of the “nameless stamps” were the earliest issues of that country. Austria’s first stamp was issued in 1851 and depicted the national coat of arms.

At first glance, it might appear that this stamp came from a country named “Kreuzer,” as that inscription at the bottom of the stamp is the most prominent word on it. However, that is the name of the currency, and the numeral “1” that precedes “kreuzer” helps to indicate that this is the stamp’s denomination. In 1883, the country name “Oesterr” appeared on Austrian stamps for the first time.

By the way, identifying stamps can be made a bit easier if you are familiar with the names of currencies used by various countries.

Many stamp-identification books have lists of currency names, and you can find websites with such information by entering “historical currencies of world” or similar wording in your favorite search engine.

Currencies also are listed in the demographic information that appears at the beginning of each country listed in the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue and Scott specialized catalogs.

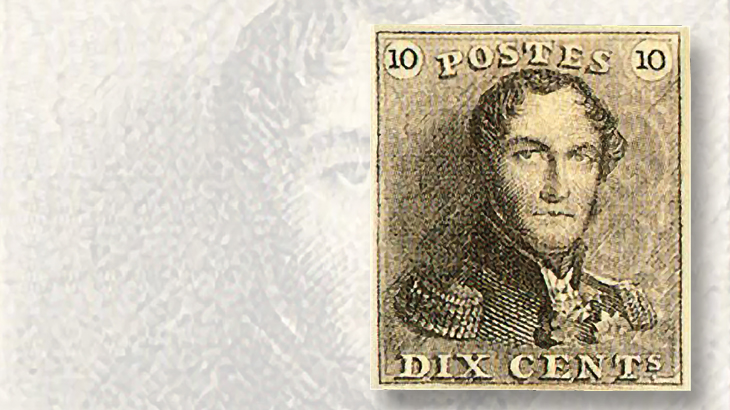

Belgium’s first stamp has a portrait of King Leopold and was issued in 1849. During this early stamp period, countries such as Austria and Belgium relied on designs of their coat of arms and ruling monarchs to indicate the identity of the issuing nation.

That method of self-identification may have worked at the time, but it certainly makes it difficult to add such stamps to your album 150-plus years later. Training your eye to recognize that Belgium’s coat of arms has a standing lion facing left will help, at least over time as you work with your new stamp acquisitions. Belgium began issuing stamps with the name “Belgique” on them in 1869.

In 1879, Bosnia and Herzegovina issued its first stamps without a country name but with a coat-of-arms design showing eagles and a lion. (Some stamps of this country issued from 1918 to 1920 are found in the Scott Standard catalog at the beginning of the Yugoslavia listings.)

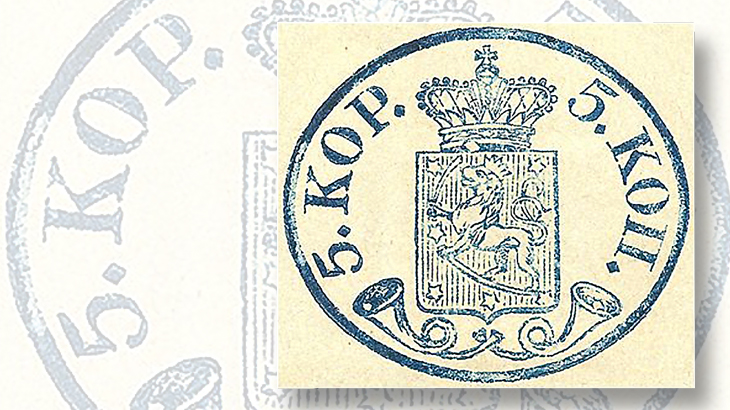

Finland’s first stamp, issued in 1856, when it was a duchy of the Russian empire, also uses a coat of arms, and the denomination in Russian kopecks.

Finland relied on its coat of arms in place of the country name until 1875. Thereafter, stamps continued for quite some time to display the coat of arms, but also contained the words “Finland” (the country name in Swedish) and “Suomi” (in the Finnish language) in the border of the design.

Unlike many of its fellow nations, France resolved in its early stamp-issuing years to make certain its name was on its stamps. But, in 1938, France issued a set of Ceres stamps (Scott 335-340, depicting the Roman goddess of plants) where “Republique Francaise” was not spelled out. Instead, each of the upper corners of the stamp has a highly stylized “RF” monogram that is not easily read (the letters are actually backwards in the right corner). Thereafter, many stamps were inscribed “RF” while Republique Francaise was spelled out on others.

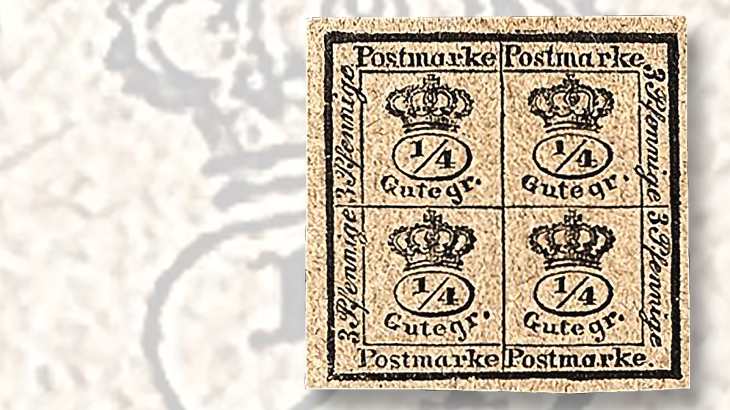

The German states of Baden, Bremen, Brunswick, Prussia, Thurn and Taxis, and Wurttemberg all issued stamps without the state’s name. In 1857, the German state of Brunswick issued a single 1-gutegroschen (ggr) stamp that could be divided into four tiny ¼ggr stamps, or broken into fractions of ½ggr and ¾ggr. Neither the intact stamp nor any of its smaller increments have the state’s name.

Some nations, such as Greece, Montenegro, and Thrace, have their names spelled out on the stamps, but the names are in the Greek alphabet.

Early Greek stamps, of 1861, depict the god Hermes, and are inscribed with the Greek letters epsilon, lambda, and lambda (these letters resemble an “E” followed by two inverted “V”s), which form a shortened version of the name for Greece in that language (“Ellada” in English transliteration).

The more modern spelling of Greece on stamps uses the letters epsilon, lambda, lambda, alpha, and mu. Mu is a letter that resembles a capital “M” tilted left at a 90-degree angle.

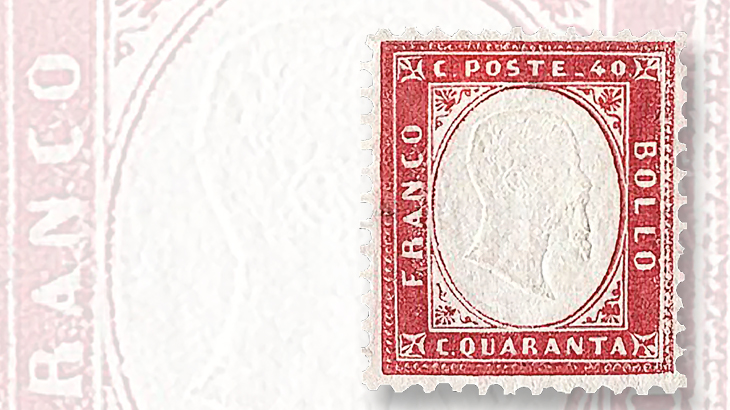

Italy’s first stamps have an embossed image of King Victor Emmanuel II, with the denomination written in the border, but lacking a country name. The word francobollo (“stamp” in Italian) and the denominations spelled out in words such as quaranta (“40” in Italian) help to identify the country, if you don’t recognize Victor Emmanuel.

Online translation services, such as Google Translate or Babelfish, can be very useful in such instances. Decipher any word that you see on a stamp, and you should be able to pin down the language, providing a major clue regarding the issuing country, even if the stamps are from a colony or an occupied nation.

As with the German states, Italian states issued stamps without the state’s name. Modena, for example, used a coat of arms to identify itself on its first stamp, in 1852.

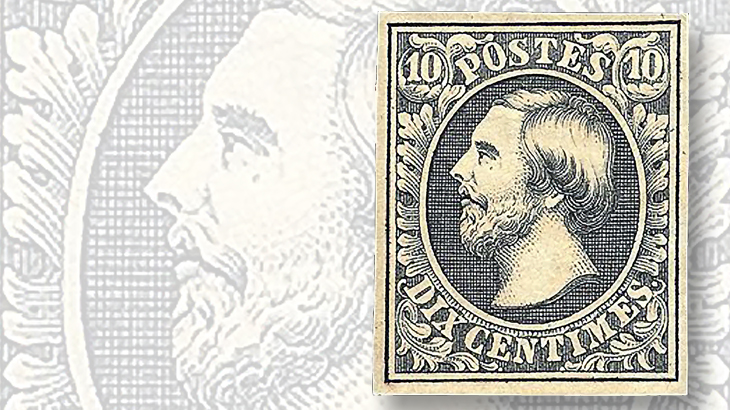

Luxembourg’s first stamp, in 1852, used only its monarch, William III, king of the Netherlands and grand duke of Luxembourg, as identification. In 1859, with Scott 4, Luxembourg stamps began carrying that name.

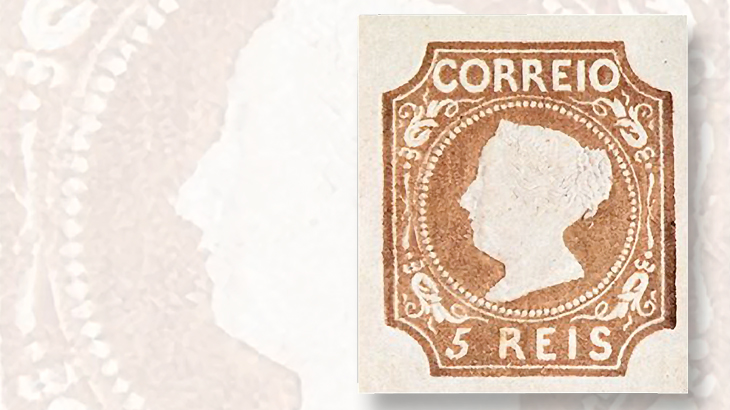

Portugal’s first stamp, in 1853, bore a portrait of Queen Maria II, but its stamps did not say “Portugal” until 1866. The word correio, Portuguese for “mail,” is a hint of the country of origin on the earlier stamps.

Nearby Spain also portrayed Queen Isabella II on its first stamp, in 1850. The first stamp with its country name — for Spain — was in 1862, Scott 55. Correos, Spanish for “post” or “mail,” is a good clue on the pre-1862 issues.

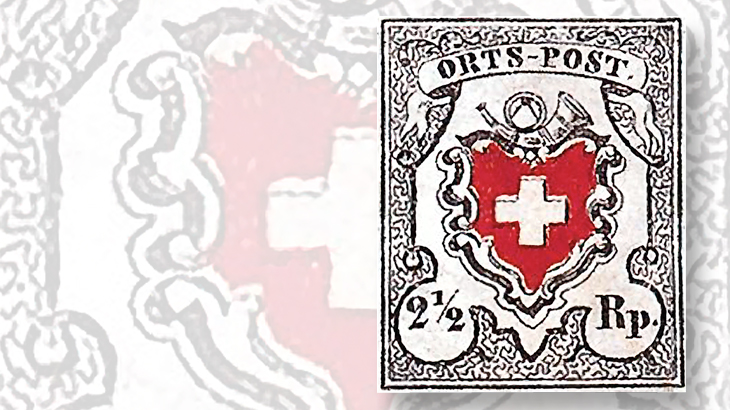

Yet another European coat-of-arms stamp made its debut in 1850 in Switzerland, but it wasn’t until 1862 that a stamp inscribed with that country’s name appeared: Helvetia, the Latin form of Switzerland, and still one of its official names.

That covers most of the European countries that issued stamps without a country name, but similar challenges remain for a future discussion.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers