Postal Updates

Remembering the legacy of Underground Railroad operative William Still and his family

Delivering the Mail by Allen Abel

Iron rusts, paint fades, fields forget and a humble cabin’s wooden frame collapses with the centuries. But the most powerful stories never expire. They are kept alive by families, by the written word and sometimes even by a postage stamp that presents a humble human face.

So it has been with the extraordinary saga of William Still; his mother, Charity; and his brothers, Peter and Samuel, who were torn apart by slavery, undefeated in spirit and reunited in one of the most poignant scenes ever put to paper.

On March 9, William Still (1821-1902) was one of 10 19th-century Americans to be honored on a set of United States nondenominated (68¢) forever commemorative stamps honoring operatives on the Underground Railroad.

[Editor’s note: Charles Snee’s article about the new Underground Railroad stamps was published in the March 4 issue of Linn’s Stamp News.]

Each contributed in his or her own way to the network of night runners and safe houses that delivered thousands of Black women, men and children to the American North and British Canada.

“Like millions of my race, my mother and father were born slaves, but were not contented to live and die so,” William Still wrote in The Underground Railroad A Record of Facts, Authentic Narrative, Letters, &c.

“My father purchased himself in early manhood by hard toil,” William continued. “Mother saw no way for herself and children to escape the horrors of bondage but by flight. Bravely, with her four little ones, with firm faith in God and an ardent desire to be free, she forsook the prison-house, and succeeded to reach a free State … ”

William’s detailed indelible narrative was published in 1872 after the Civil War and is still in print.

But Charity Still was not long free. Snared by slave catchers in New Jersey, she was remanded back to the South. There, one night, she fled again, after making the agonizing choice to take two more of her youngest daughters with her and leave two little sons behind.

“Can you imagine the anguish of a woman leaving children behind?” Samuel C. Still III told Linn’s in an early February telephone interview from New Jersey. “I don’t know what I would be thinking if I were in those shoes, and yet we have dozens of stories of people escaping slavery but having to leave their children behind.”

Samuel Still, a U.S. Army engineer, is the executive director of the Dr. James Still Historic Office Site and Education Center in Medford, N.J.

The site’s small brick building and a reconstructed cabin near the farm where Charity Still was shackled in servitude in Caroline County, Md., are physical evidence of the generations of Stills who suffered and fled and then grew and prospered. James Still, a herbalist and healer, was one of William’s siblings, but there also was a brother named Peter.

In 1850, after 40 years in slavery, Peter was able to ransom his liberty from his owner, a man named Joseph Friedman, for $500.

Peter made his way to the shores of the Delaware River, not knowing that his elder brother William was serving there as the chairman of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, having helped an estimated 1,500 freedom seekers follow the North Star.

One night, a woman who had provided Peter with lodging brought him to see William.

“Here is a man who tells a strange story,” she is quoted as saying in The Kidnapped and the Ransomed. Being the Personal Recollections of Peter Still and His Wife, “Vina,” After Forty Years of Slavery, published in 1856. “He has come to Philadelphia to look for his relations, and I should like to have you hear what he has to say.

“She turned to Peter. ‘For whom are you looking?’ ” she said.

“ ‘Oh,’ he replied, ‘I’m a lookin’ for a needle in a hay-stack: and I reckon the needle’s rusty, and the stack is rotted down, so it’s no use to say any more about it.’ ”

“He proceeded to repeat his story,” according to The Kidnapped and the Ransomed, “but when he spoke the names of his father and mother, his listener could sit still no longer. Seizing the candle, and holding it near his face, he cried, ‘O Lord! It is one of our lost brothers! I should know him by his likeness to our mother. Thank God! One of our brothers has come.’ ”

It might be that every African American family has a story this powerful. But the Still brothers put theirs to paper, and the paper endures.

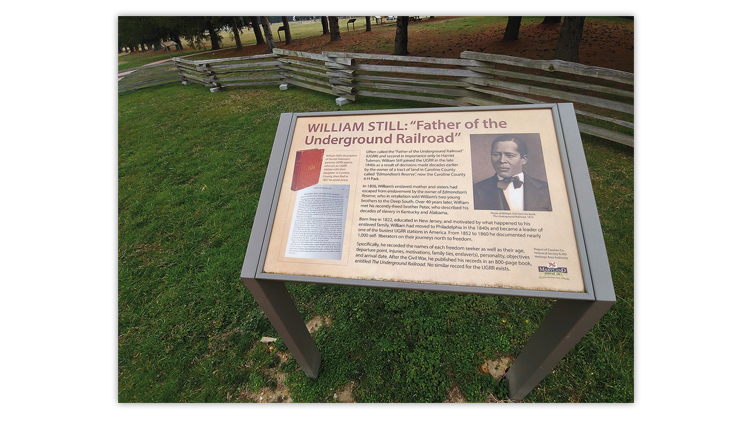

“The New York Times in its obituary in 1902 proclaimed William Still to be the father of the Underground Railroad,” Samuel Still said. “We all understand that the Underground Railroad didn’t start with him, but he was the only one who kept records of all of the escaped people who came to Philadelphia, and that book that he wrote in 1872 is still used today by families trying to locate their ancestors.”

“I hope that when people see these stamps and they look at William Still and his brothers they realize what being an African American man during those times meant,” Samuel said. “It meant that we had intelligence, we had dedication, we loved each other and this is home for us.”

“We all share a story of a contribution to America,” he asserted. “We’re all a part of this big melting pot. We all have a serious contribution to make to the growing of this nation and we can all respect each other a little more than we do.”

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers

-

World Stamps

Oct 5, 2024, 1 PMCanada Post continues Truth and Reconciliation series

-

US Stamps

Oct 4, 2024, 6 PM86th Balpex show set for Oct. 25-27 at new location