US Stamps

Essays and Proofs: Interest in Henry Lowenberg’s essays

The National Bank Note Co. considered Henry Lowenberg to be a worthy adversary when it came to developing ideas that would receive patents for the prevention of reuse of postage stamps.

My previous column (Linn’s, Nov. 24, page 30) described how his starch-coated paper patent was adapted for use and experimented with by National.

Lowenberg received three other patents, all of which could be considered a threat to Charles Steele’s grilling process, which was the anchor that kept the postage stamp printing contract at National during the latter part of the 1860s.

Both of Lowenberg’s other patents involved the use of the decal process, similar to the process we use today to put insignia on model planes or vehicle stickers on automobiles.

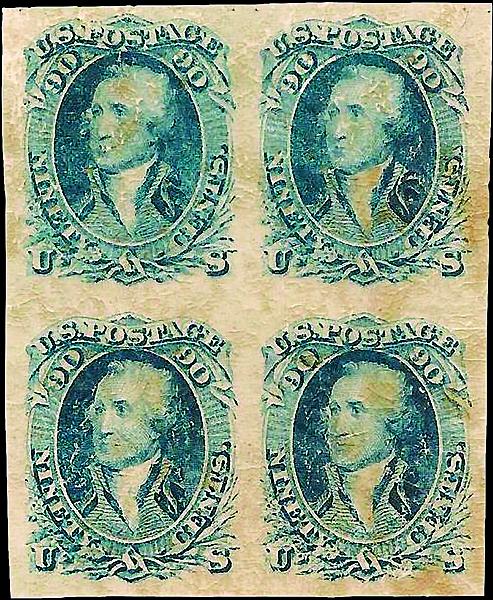

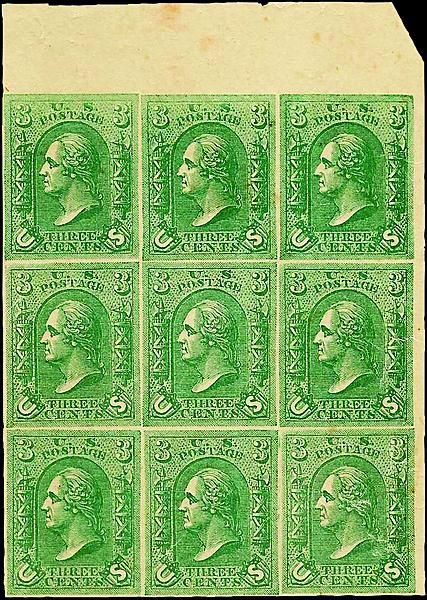

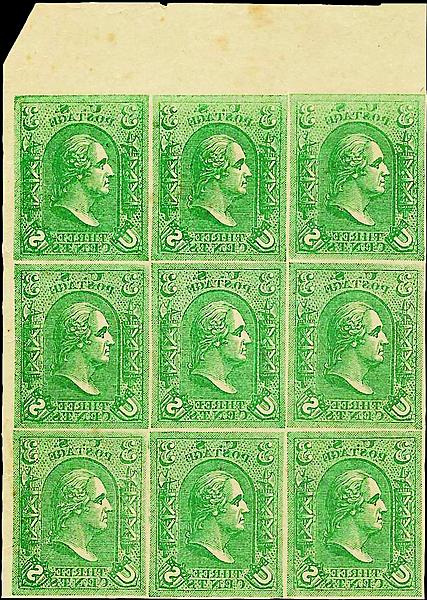

The early experiments he conducted utilizing his patents involved using the lithographic printing process to print on onionskin paper, a paper similar to the tracing paper once used by architects or typists to create additional copies of an original.

The design was printed in reverse on a sheet of onionskin paper and then gummed on that side as well. Because this paper is nearly transparent, you can clearly see the image as it is meant to be seen when you turn the paper over.

The side-by-side illustrations on this page of the 3¢ green essays demonstrate this.

Once you licked the stamp, affixed it to an envelope and it was canceled, you could not remove the stamp and reuse it. Soaking the paper to remove the cancel would cause the onionskin to come off, and it would leave part of the design on the envelope.

Lowenberg had created a cheap and effective means for providing the government with postage that never saw use.

He next modified his process to include the use of goldbeater’s skin to be the carrier of the stamp image. This proved to be a more effective way to cause the destruction of the image when it was soaked in water.

This patent was more successful than the first and caught the interest of the United States Treasury Department. The Treasury had been printing revenue stamps since 1862 to finance the American Civil War, and Lowenberg had developed a way it could reduce that cost.

There exists a contract to supply the Treasury Department with 10,000 2¢ bank check stamps in five colors. A copy of the contract, signed by Lowenberg, was found in the Brazer/Finkelburg papers that I purchased from the Finkelburg estate in 1999. It will be featured in the second installment of this article.

Related posts from Linns.com:

- National Bank Note's proofs testing patents to prevent reuse

- Essays and Proofs: Henry Lowenberg’s experiments to prevent stamp reuse

- Exploring United States postage stamp essays and proofs

While there is evidence that the contract was fulfilled, there are no surviving examples of the stamps having been used.

The patent for the goldbeater’s skin process also must have caught the attention of the National Bank Note Co. Sometime after 1867 that firm began experimenting with this process.

However, instead of employing lithography, National used steel engraved plates that were already in production, producing stamps for the U.S. Post Office Department.

A number of plate number position pieces have survived to prove this, and will also be featured in the second installment of this article.

In order for National to have experimented with the Lowenberg process, they would have had at the very least a licensing agreement with him. Just read through all of the subvarieties on page 797 in the 2015 edition of the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers. His lithographic process was tried on thick wove paper printed with fugitive ink, glazed paper, chemically treated paper and even on linen cloth.

My next column will continue to explore the work of Lowenberg, and will show how one country adapted one of his patents to print postage stamps that saw actual use through the mails.

James E. Lee has been a full-time professional philatelist for more than 25 years specializing in United States essays and proofs, postal history and fancy cancels.

He may be reached via e-mail at jim@jameslee.com, or through his website.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers