World Stamps

The Black Honduras and Red Honduras saga

The stamp known as the Black Honduras, believed to be unique, is the world’s rarest airmail stamp. The Red Honduras, with no more than seven available to collectors, is the second rarest.

Both were issued in 1925 when Central America’s first airline inaugurated service between the Honduran capital city Tegucigalpa, in the interior of the country, and Puerto Cortes on the Caribbean coast.

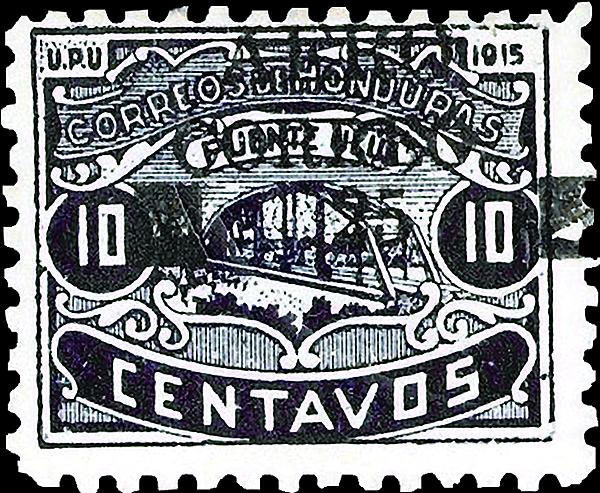

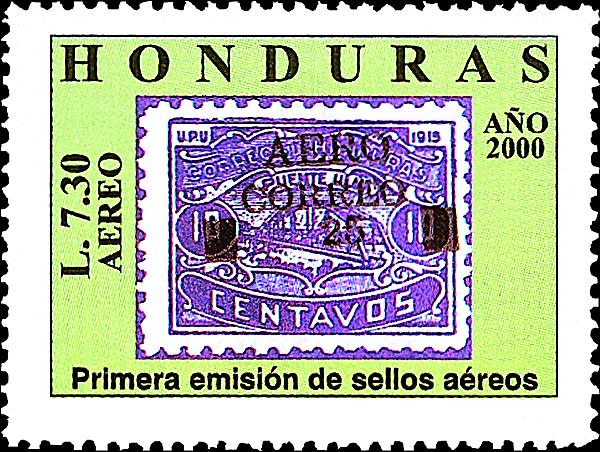

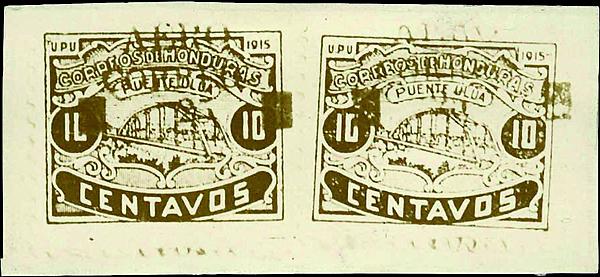

Considering their legendary names, it may seem odd that the Black Honduras is a dull blue stamp and the Red Honduras is a bright blue stamp. That’s because they are defined by the ink colors of the overprints on them, which transformed the underlying common definitive stamps into airmail rarities — the 10-centavo Ulua Bridge stamp surcharged AERO CORREO 25 in black ink (converting a 10c ordinary stamp into a 25c airmail stamp, Honduras Scott C12) and the 5c Bonilla Theater stamp overprinted AERO CORREO only in red ink (C3).

First-issue airmail stamps of Honduras are important to philately in the same way that United States airmail stamps of 1918 are important, as historical artifacts of the service that created them. But airmail service was of greater relative significance to Honduras than the original U.S. government airmail service.

Tegucigalpa was isolated from the outside world, with no rail transport and with roads so poor that mule trains took up to a week to carry mail to a port on the north coast for onward transmission to other countries.

The small aircraft flown by Compania Aerea Hondurena (also advertised as Central American Airlines [CAA]) traveled the 200-kilometer distance in about an hour and a half.

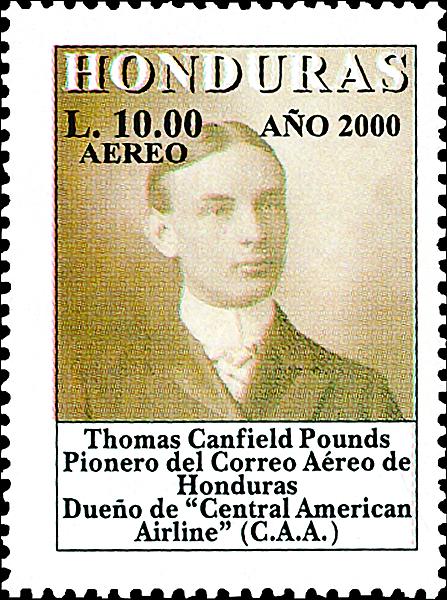

Thomas Canfield Pounds, M.D.

On Oct. 24, 1922, the postmaster general of Honduras contracted with an American physician named Thomas C. Pounds to establish airmail service between Tegucigalpa and the north coast.

The Honduran president, Lopez Gutierrez, approved the contract on Dec. 16. A 10-lempira stamp issued by Honduras in 2000 pictures Pounds (Scott C1076).

Pounds was born Aug. 9, 1876, in Montana. Philatelic legend holds that Pounds was related to Kid Canfield (Richard Albert Canfield), a notorious turn-of-the-20th-century gambler and confidence man turned anti-gambling reformer, author, lecturer and subject of a 1920s Western silent motion picture, but I have been unable to verify that.

Pounds graduated from Cornell University in the “Senior Medics” class of 1902 and earned his M.D. degree from the University of Southern California School of Medicine in 1903.

He established a prosperous eye, ear, nose and throat practice in Redlands and San Diego. On March 28, 1905, he married Marion Ashley of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Almost immediately, the Poundses became respected celebrities of San Diego civic affairs and high society, noted in local news snippets.

In 1910 Pounds taught San Diego schoolteachers how to detect and prevent eye, ear and throat diseases in children. In 1913 the exclusive Sequan Country Club was incorporated with Pounds as its president, its membership limited to 100 families.

In 1915 Marion Pounds was proposed as a candidate for the San Diego school board at a meeting of politically active women, an uncharacteristically progressive suggestion before women had won the right to vote throughout the nation.

Pounds served as an assistant surgeon in the naval reserve, achieving the rank of lieutenant from 1915 to 1918, but was never called to duty during World War I. A Jan. 1, 1917, report in the San Diego Union boasted that the town’s most prominent citizens, including Pounds, were “citizen sailor” members of the Navy Militia, part of a grand and largely successful campaign to transform San Diego into the Navy’s main Pacific coast base.

After the war, Pounds moved his residence to Tegucigalpa and established himself there as an eye doctor.

He is said to have witnessed the first airplane flight in Central America on April 19, 1921, when his friend, Col. Ivan Lamb, flew his Bristol fighter into Tegucigalpa from San Pedro Sula, which kindled his interest in the aviation business.

The Inauguration of Air Transport in Honduras

Sumner B. “Sonny” Morgan had been an aviator for a decade or more by the time he applied for the job as CAA’s pilot. He had worked for Glenn H. Curtiss’ Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co. in 1916, and had studied motor design at Columbia University.

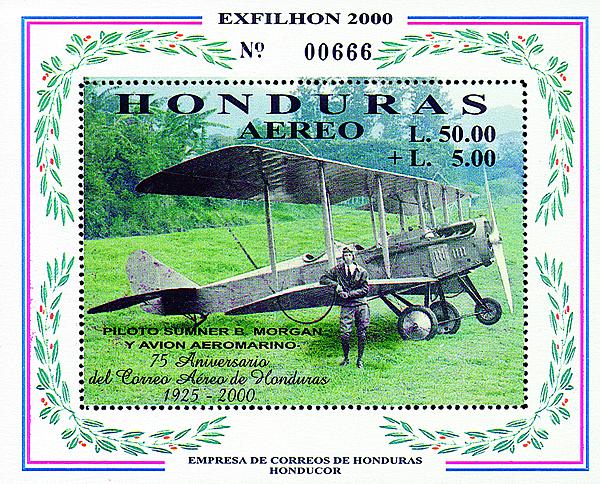

The inaugural CAA flight took off from Toncontin Airport in Tegucigalpa on April 30 or May 1, 1925, piloted by Morgan, and flew to Puerto Cortes on the Caribbean coast. Honduras commemorated the 75th anniversary of that flight with a souvenir sheet that pictures Morgan and his Aero-Marine airplane (Scott CB5).

The flight carried 29 letters, of which seven were franked with only ordinary postage, and 22 were franked with both ordinary and special airmail stamps.

By the end of June, 100 letters flown from Tegucigalpa and 773 letters flown on return flights from Puerto Cortes had been franked with the special stamps.

Thus, the special airmail stamps of Honduras achieved not only postal and philatelic legitimacy, but cherished status as icons of the airmail age.

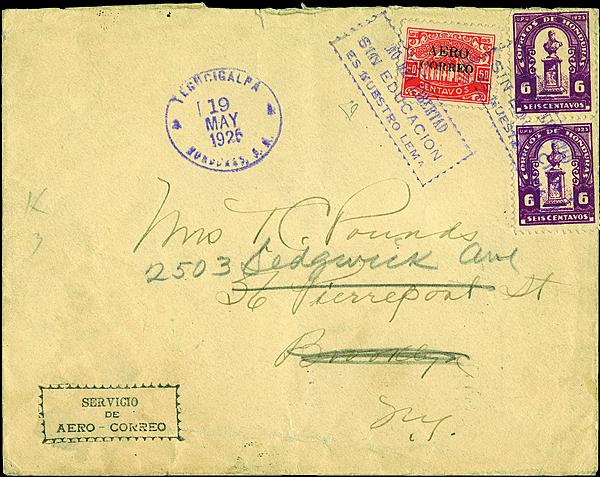

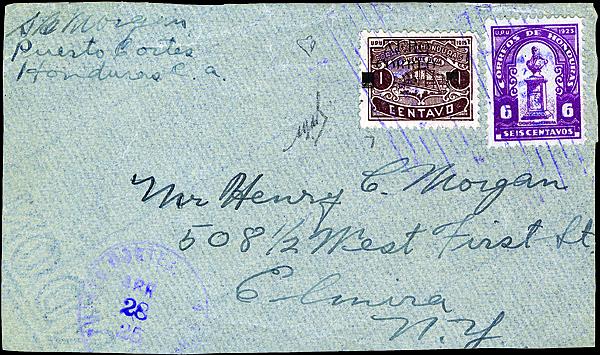

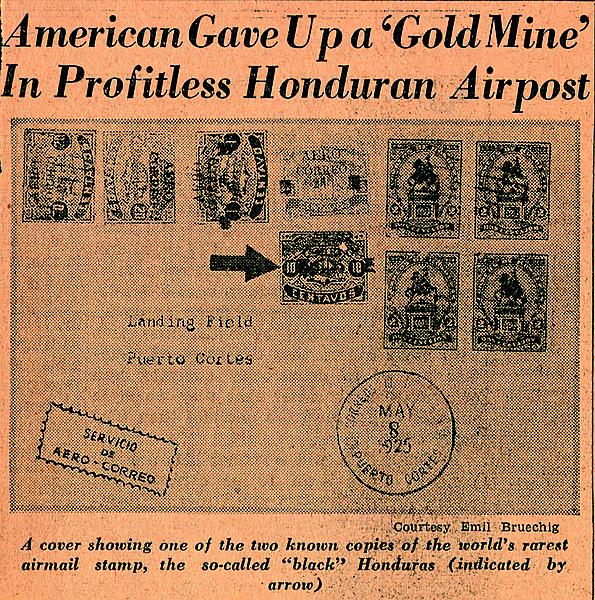

Morgan probably carried the illustrated cover, postmarked April 28 at Puerto Cortes, on the first flight.

Pounds sent the cover postmarked May 19 at Tegucigalpa to his wife in Brooklyn on a later flight.

Special Airmail Stamps

Early adventures in powered flight and polar exploration were often promoted and funded by special issues of postage stamps and by the sale of souvenir cards and covers that were carried by the aviators and explorers on their trips, so it wasn’t surprising or unusual that Pounds’ contract allowed him to finance his enterprise in part with a special postal issue.

An April 29, 1925, announcement of the new air service from the Tegucigalpa post office listed the rates and explained the procedures to members of the public, including the use of the special stamps (as translated by John N. Myer in the August 1940 American Philatelist):

The correspondence which will be carried from this city to the North Coast by airplane will bear two stamps: the ordinary postage of the Government, according to the current tariff, and the postage of the special stamp of the enterpriser. …The special stamps will be sold by Dr. T.C. Pounds in this city, and by his Agents in the other places where correspondence is to be carried by air.

Myer quoted from Pounds’ contract: “The Government will order printed for its account special postage stamps for franking the correspondence which is carried by airplanes and the entire product of the sale of these special stamps will be paid to the contractor monthly.”

As things turned out, the government did not provide the stamps, so Pounds arranged for his business associate Karl J. Snow to add surcharges to stamps of a regular issue on a Kelsey-Excelsior manually operated press.

Snow had been using his press to print 3-inch-by-5-inch religious tracts for the Seventh Day Adventist church. That small format limited the number of stamps that could be overprinted at one time. The airmail surcharges were applied to blocks of 12, and to smaller leftover pieces from the original panes of 100.

Each position of the 12-subject overprint setting differed from the others in consistent traits, so every genuine stamp can be plated.

Some stamps on the original pane were inverted in relation to their neighbors, yielding scarce tete-beche pairs (or, when separated, single stamps with inverted overprints).

Pounds, Morgan and their associates were aware of philatelic interest in their stamps, which quickly made their way to the hobby market. In the United States, the flamboyant dealer Albert C. Roessler of East Orange, N.J., promoted Honduran airmail stamps and covers. Covers that Roessler sold were probably favor canceled but not flown. Before the end of 1925, the notorious forger Raoul Ch. de Thuin had produced quantities of forgeries (forged overprints on genuine stamps).

Discovery of the Black Honduras:the Ustariz Single

When stamp catalogs listed the first airmail stamps of Honduras in 1925, the Black Honduras was not among them. The June 1925 issue of Bulletin Mensuel de la Maison Theodore Champion reported that the Honduran postal administration had announced stamps issued April 28 to pay a surtax on letters carried by air between Tegucigalpa, the capital, to the north coast of Honduras, and published the list of airmail rates.

Champion listed stamps of the 1915 issue overprinted AERO CORREO as follows, noting the ink color if not black: 5c blue, issue of 500, exists with inverted surcharge; 10c blue (red), 500, exists with tete-beche and inverted surcharge; 20c on 1c brown-violet, 500, exists with inverted surcharge; 50c rose, 200; 1 peso green, 100. But no 10c blue with a black overprint.

In March 1927, John Luff, a senior dealer at Scott Stamp and Coin Co. and editor of the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue, received a large batch of Honduran airmail stamps from Julio Ustariz, owner of the airfield at Puerto Cortes, which included one 10c blue overprinted 25c in black. Ustariz had obtained the stamps from his friend F.W. Budde, who had obtained them from Pounds in March 1926.

Luff plated the previously unreported stamp to assure that it was not a forgery, and satisfied himself that the overprint was genuine from the first printing. Not having known of its existence earlier, Luff suspected that it may have been a trial print, but his queries drew conflicting reports from his correspondents.

To avoid disclosing its seeming scarcity, Luff hinted to Ustariz that it was probably counterfeit after he had satisfied himself that it was genuine. Luff never returned the stamp to Ustariz, and never paid for it.

Thus, the first example of the Black Honduras is known as the Ustariz single.

Tragedy of Duran Membreno’s Black Honduras Pair

Also in March 1927, Luff received a batch of 16 Honduran airmail stamps from Raul Duran Membreno, a Tegucigalpa dentist who was later secretary general of the postal administration.

Duran was a stamp collector and dealer who had obtained his stamps from Pounds. (Duran was his surname, and Membreno was his mother’s maiden name, in the Spanish rendering, but American stamp writers failed to recognize that distinction so he is known to philately as Membreno.) He enclosed a pair of 10c stamps surcharged in black for Luff to examine and perhaps explain.

The second and third examples of the Black Honduras are known as the Membreno pair.

Luff returned 14 of the 16 stamps, but retained the pair, which he had determined to be genuine, for further study. While playing down its scarcity and potential value, he tried to persuade Duran to sell it, but Duran demanded the pair be returned to him for his own collection. Luff reluctantly complied.

In November 1927, Duran wrote to Luff that his collection had endured “an accident” and that “My two 25c/10c blue airmails were lost.” The Membreno pair has not been seen since, but the Philatelic Foundation has the photograph that Luff kept with his reference collection.

The Robinette Single,Last of the Original Four

Finally, in June 1930, Washington, D.C., stamp dealer H.A. Robinette sent Luff “a Honduras airmail surcharged ‘25 on 10’ blue. This came to me [Robinette] with a small collection of these stamps which are undoubtedly genuine and the original owner claims to have bought them all, right at the post office in Honduras.”

The fourth example of the Black Honduras is known as the Robinette single.

Overprints on the four recorded examples of the Black Honduras have top row consecutive positions of the original overprint setting, but the underlying stamps came from different, widely separated, positions of their original pane, which is part of the reason specialists doubt that more than those four ever existed.

The four stamps had been grouped together for overprinting. Plating established that in the 12-subject setting, the Robinette single overprint was from position 1; the Ustariz single, position 2; the Membreno pair, positions 3 and 4. When images of all four were examined together, even the overprints on the partially separated Membreno pair aligned.

But they had not been an attached strip of four. The Robinette single was position 40 on the original pane of 100 stamps, and the Ustariz single was position 60, the last stamps in two different horizontal rows.

Had the overprint positions not been consecutive or had the original stamps been taken from a single block of 12, there would be reason to suspect that more had been printed. But this unusual combination and the fact that no others have been found since 1930 are good reasons to doubt that any more were made with the black surcharge on the 10c stamps.

The poor quality of the overprint and the original use of black ink later replaced by red suggest that this Black Honduras patched-together strip was a trial print of the setting, perhaps to check the placement of the black squares that obliterated the original denomination. Nevertheless, even if it had been a trial print, at least one of the stamps had been sold at a post office as a normal issue, according to Robinette’s source.

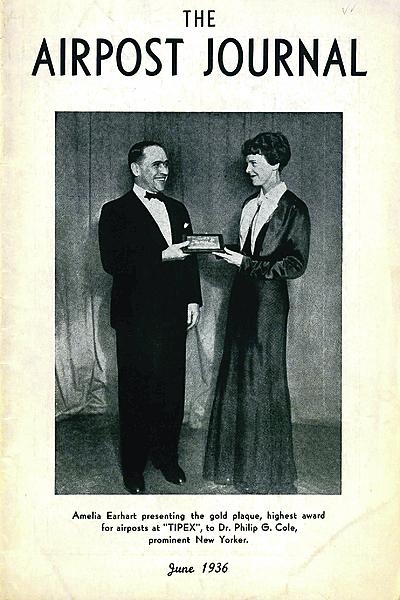

Grand Award at the 1936 Third International Philatelic Exhibition

In the absence of contrary evidence, Robinette’s report should have satisfied Luff’s dithering about whether the Black Honduras had been an issued stamp, not simply a trial print, but Luff still did not list the stamp in the Scott catalog while he hoped to buy it cheaply from Robinette “as a trial stamp or an essay.”

Robinette was no fool. He instead sold it to the airmail dealer Nicolas Sanabria. Sanabria sold it to the New York airmail dealer Fred W. Kessler, who sold it to Philip G. Cole, a famous collector of Western art who had the finest airmail collection then in existence.

The stamp was finally placed on public view in 1936 as part of Cole’s exhibit at the Third International Philatelic Exhibition in New York City. By then, with only two known examples still likely to exist, it should have been recognized as the world’s rarest airmail stamp, but that was not to be.

Instead, the Red Honduras, of which only seven were collectible, was highlighted. Amelia Earhart presented the Tipex grand award in the airmail class to Cole as airmail collectors celebrated his achievement, but no report paid special attention to his Black Honduras.

Origin of the Red Honduras

In 1926 John W. Nicklin, the Scott Stamp and Coin Co. buyer, purchased a large batch of Honduran airmail stamps from Morgan, the pilot. Morgan had taken the stamps in lieu of money Pounds allegedly owed him. Among the hoard was a single irregular block of nine Red Honduras stamps.

Honduran correspondents had advised Luff that only a single block of 12 had been printed, so he recognized the rarity of the stamps. Two were so badly scuffed that they were deemed unfit to sell; those went into his reference collection. Nicklin sold the other seven to these wealthy collectors: U.S. Sen. Joseph S. Frelinghuysen, Charles C. Lieb, Oscar R. Lichtenstein, Fuller Heathcote, Donald R. Davis, Carlton W. Smith and G.B. Towne.

By the time Cole had won the Tipex grand award, the Red Honduras was famous. In the Sept. 24, 1932, issue of Stamps magazine, airmail dealer Emil Bruechig’s article “The Rarest Air Mail Stamp — Honduras 5c Surcharged in Red” had summarized the production of the 1925 set, and then declared, “But the specimen of this issue that outshines them all is the five-cent light blue, surcharged in red!”

But by 1936, someone should have reported that the Black Honduras was rarer. The reason for the omission was a mistake by Sanabria. He had listed the Black Honduras in the 1936 first edition of Sanabria’s Air Post Catalogue, but had reported the quantity issued as 12 stamps, and had assigned it a value of $4,000, compared to seven stamps valued at $7,000 each for the Red Honduras.

Sanabria repeated his mistake in the 1937, 1938, and 1939 editions (each published in the year preceding the cover date). He must have believed that one block of 12 had been surcharged, and that all of the stamps from that block might have survived.

As this confusion spread, the forger de Thuin was making matters worse. In the British magazine Stamp Collecting for Dec. 7, 1935, and Jan. 4, 1936, de Thuin’s article “The First Air Stamps of Honduras (1925)” reported the history reasonably accurately from the perspective of a writer who had been an associate of Pounds, thus adding an aura of credibility to the author’s widely marketed forgeries.

Recognition for the Black Honduras

John Luff died Aug. 23, 1938, and very quickly things began to change.

A Sept. 24 NBC radio report announced the discovery of a second example of the Black Honduras in addition to the one that Cole had exhibited at Tipex. The Oct. 8, 1938, issue of Stamps magazine published an article titled “The World’s Rarest Air Mail Stamp” by Prescott Holden Thorp that provided more information, though no details of when or by whom the discovery had been made.

Thorp’s article pictured a May 1925 cover franked with both ordinary and airmail stamps of Honduras. One of the airmail stamps was the 10c blue surcharged 25 in black, a Black Honduras. Thorp submitted the cover as evidence to refute Luff’s catalog note that the stamp “is not known to have been put in use.”

The cover was actually in the possession of stamp dealer Bruechig — the man who had previously promoted the Red Honduras as the world’s rarest airmail stamp. Bruechig showed the cover not only to Thorp but also to Hugh Clark, who had succeeded Luff as the Scott catalog editor. On that evidence, Clark listed the Black Honduras as a legitimate issued stamp. Several months later, after the stamp had been accorded official recognition, Bruechig’s cover illustrated an article in the New York Herald-Tribune.

It later transpired that the stamp had not originated on the cover, but was the unused Ustariz single that Luff had failed to return in 1927. It may have been added fraudulently to the cover as a way of disguising its origin. Ustariz was not fooled, and was angry that Luff had led him to believe it was a forgery, but his complaint that Luff had “stolen” the stamp from him had no influence on events.

In 1953 Nicklin told writer Irving R. Green, “The story is this: The stamp on the cover, was sold; it was later cleaned [fake cancel removed] and regummed.” Green believed that “Bruechig had sold it to his best customer, Dr. Lieb of New York City.”

But when John A. Fox sold the Dr. Charles C. Lieb Collection of Airpost Stamps of the World in his Feb. 25-27, 1957, estate sale, the Black Honduras was not included. Green pursued a rumor that “a wealthy Mid-Westerner had obtained it,” but was unable to confirm it. At that point, the Ustariz single disappeared from view and dropped out of hobby lore.

Record Sale Prices for the Robinette Single

On Oct. 27, 1939, Kessler sold at auction the Famous “Dr. Philip G. Cole” Collection of Rare Airmail Stamps & Covers. The Black Honduras realized $5,300, purchased by Sidney F. Barrett of Economist Stamp Co. for Oscar R. Lichtenstein. Sanabria corrected his listing in the 1940 edition of his catalog, showing that only two examples of the Black Honduras were known (the Robinette and Ustariz singles), with an assigned value of $15,000.

Lichtenstein died in 1955. Harmer, Rooke sold his collection at auction in 1957. The next owner of the Robinette single was Thomas A. Matthews of Ohio, who built the finest airmail collection of all time. Matthews paid $11,500 for the Black Honduras at the Lichtenstein sale.

When Kessler sold the Matthews collection on Feb. 27, 1961, Raymond H. Weill of New Orleans bought the Black Honduras for $24,500, which set a record for any stamp sold at auction in America. Only one stamp had previously sold for a higher price — the 1856 1¢ Magenta of British Guiana.

The underbidder who dropped out at $24,000, retired weekly newspaper publisher Max L. Simon, was missing only two stamps in his worldwide airmail collection. He had reckoned on just three competitors: “One of them is in London, one in Rome and another in Cairo.” But after the sale, Weill told Simon the buyer was “a wealthy Texan” who had authorized him to bid as high as $30,000. To my knowledge, the identity of Weill’s client has not become public.

From Josiah K. Lilly Jr. to Joseph Levy Jr.

The Robinette single made its next appearance in Robert A. Siegel’s 1968 sale of the Josiah K. Lilly Jr. philatelic estate, where a consortium of New York stamp dealers purchased the Black Honduras for $29,000. The buyers displayed it anonymously at Anphilex 1971, the Collectors Club’s 75th anniversary exhibition.

On Feb. 6, 1976, Jared Johnson, proprietor of the Chandler’s Inc. school and office supply chain in Evanston, Ill., purchased that Black Honduras from Andrew Levitt for a price in excess of $80,000 on behalf of Joseph Levy Jr., owner of the world’s largest Buick and Chrysler dealerships, also located in Evanston.

Besides being a showpiece at Chandler’s store, Levy’s Black Honduras was anonymously displayed as a special exhibit at the Interphil 76 international stamp exhibition at Philadelphia.

Resurrection of the Ustariz Single

In the March 15, 1986, Stamp Collector, the headline over The World of Unique Stamps monthly column by Norman Williams read, “Four were printed; but one ‘Black Honduras’ only is known today.”

Two months later he published a retraction. The May 17 headline was “Unique no longer: A second Black Honduras stamp has appeared.”

After reading the first column, Raymond Weill wrote to inform Williams that his subject — the Robinette single — was not unique. In 1985 the Weill brothers had purchased a collection that included the Ustariz single, which had been certified as genuine by the Philatelic Foundation.

The Ustariz single sold for $116,670 at a May 26, 1989, Italphil auction in Rome. The stamp next appeared at the Harmer’s of London Feb. 23, 1994, sale of The Jack C. Boonshaft Collection of Airmails of the World (Part 2), where it realized £104,500, equivalent to $155,705.

The next owner exhibited the Ustariz single anonymously at Claridge’s in London, July 6-8, 1995, and at the Collectors Club centennial exhibition Anphilex 96 at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York, Nov. 28 to Dec. 2, 1996.

That was its last public appearance before the Jan. 23-24, 2002, Cherrystone sale where it was purchased by the rogue French stamp dealer Marc Rousso (also known as Armand Rousso). Less than a week later, The New York Times reported that a former FBI operations manager and two former Paine Webber Inc. executives had pleaded guilty in federal court to having illegally helped Rousso and another Frenchman “who carried out huge stock frauds in the United States and Europe. … both of whom were fugitives from French justice.”

Rousso later told members of the stamp trade he had lost the stamp after the sale, having left it in a taxi or at a restaurant by mistake. Perhaps his mind was not on stamps that day. If Rousso told the truth about his loss, the Robinette single had finally truly become unique.

2012 Cherrystone Sale of Rare Honduras Airmails

At Cherrystone’s Jan. 11, 2012, “Santa Fe” sale, Mystic Stamp Co. bought the rare stamps and covers illustrated in color with this article, including the Black Honduras, which realized $120,000, and the Red Honduras, which realized $7,000.

I’m told that “Santa Fe” was a coy reference to Edward M. Gilbert, the one-time “Boy Wonder of Wall Street” who later served two terms in prison for financial crimes. According to the Encyclopedia of Santa Fe and Northern New Mexico, Gilbert moved to Santa Fe in 1991 and founded a firm that became the largest holder of commercial real estate in New Mexico.

Despite his checkered business career, Gilbert spared no expense when he assembled outstanding stamp collections. Former auctioneer Greg Manning claimed to have sold $25 million worth of Gilbert’s collections in a series of name sales during the previous decade, so it does not surprise me to see his name on the Black Honduras provenance roster.

Mystic’s president Donald J. Sundman proudly exhibited the Black Honduras at the Aerophilately 2014 international exhibition at Bellefonte, Pa., in September. He plans to exhibit rare first-issue airmail stamps of Honduras at the New York 2016 international. It has been my personal pleasure to perform research on these stamps for Sundman.

Thanks to Mystic and the Philatelic Foundation for the images shown here.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers