US Stamps

Bureau of Engraving and Printing die proofs created between 1923 and 1961

By James E. Lee

The dawn of the golden age of United States commemorative postage stamps began with the issuance of the Harding Memorial stamp in 1923.

From that point forward, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing started to ramp up the design and production of stamps that would commemorate events marking the history of our nation.

The program would expand to include various prominent Americans, scientific and technological advances, businesses, and associations. The ever-growing number of postal emissions created plenty of work for the designers, modelers and engravers at the BEP.

As time went on, our philatelic community would eventually come into possession of some spectacular (and very rare) essay and proof material.

During the 19th century, when the private bank note companies produced our postage stamps, plenty of essay and proof material reached public hands. There was no accounting for this pre-production material, and bank note employees, such as Henry Mandel of the American Bank Note Co., regularly helped themselves to examples from the files.

Mandel funneled items to his own collection, and to the collections of Edward Mason of Boston and the Earl of Crawford in England. When the BEP took over stamp production, however, the engravers’ work became accountable. In many cases, only a single example exists today in collectors’ hands.

The Bureau required that each proof pulled in the proving room be numbered on the back. This number corresponded with the same number in the proving-room record book. The date, title of the proof, reason for the pull, and final disposition were recorded.

However, century-old trade customs stated that the engravers were entitled to a single example of their work for their portfolio. There are exceptions, which I describe here.

First there was Postmaster General Harry S. New, who had somewhere between seven and 10 sets of die proofs produced during the Coolidge Administration (1923-29). The production run included the 1922-25 regular issues (Scott 551-573), all of the commemorative postage stamps from the Harding Memorial issue through the George Rogers Clark issue (610-651), airmail stamps (C4-C11), special delivery stamps (E12-E14), and special handling stamps (QE1-QE3, QE4a).

It has been said that two sets went to President Coolidge, a set to New, and the remaining sets to other Post Office Department officials. The last time a complete set came to the market was in 1999. It had belonged to Robert Regar, a member of the executive staff of the U.S. Post Office Department.

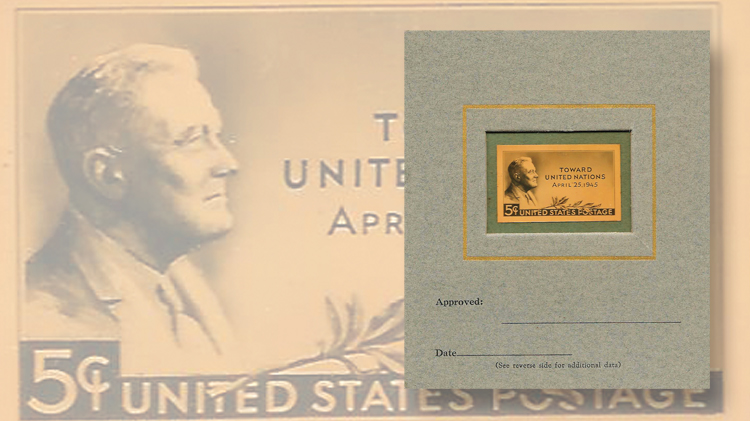

The second exception was James Farley, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s postmaster general. Farley had the Bureau produce a series of both large and small die proofs for the president. A record of these can be found in the first sale of the Roosevelt collection by H.R. Harmer Inc. in 1946.

Shown nearby is a stamp-size photo reduction of a submitted model for the 5¢ United Nations Conference issue depicting FDR that was later rejected.

Finally the Bureau itself, at different times, pulled proofs of various commemoratives going back to the 1893 Columbian issue for various exhibitions. So it is possible to find more than one example of issues from the 1920s and 1930s.

However, starting with the Famous Americans issue of 1940 and continuing to 1961, the population of proofs for any particular issue shrinks to between one and three examples. Proofs also are not known for every issue from this period.

Keep in mind that an engraver was entitled to one example of his work. It is possible that up to three engravers worked on an issue. One would be assigned the vignette, one the frame, and one the lettering.

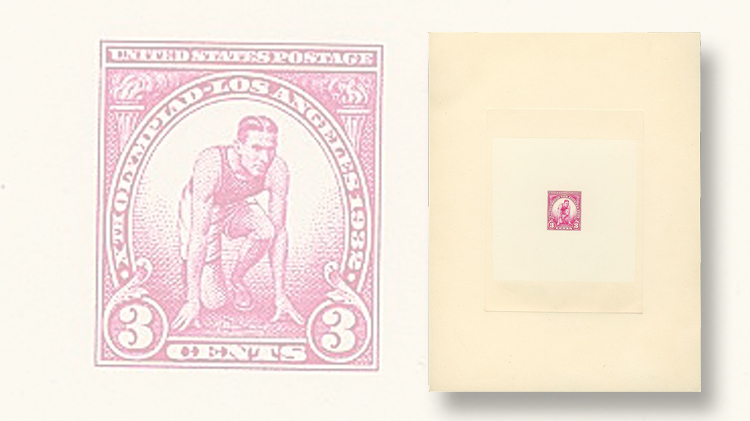

Illustrated here is a 3¢ 1932 Olympics carmine trial color, large die proof on wove paper and die sunk on card that originally was pulled for the vignette engraver, John Eissler.

At this point in time, the Bureau adopted the policy of having the engraver’s example punched with a “C” to deface the work. The BEP would actually use a punch, much like a ticket punch, to achieve this.

However, the engravers would walk out with both the proof and punched “C.” When they got home, they would reincorporate it back into the proof and tape it back into place.

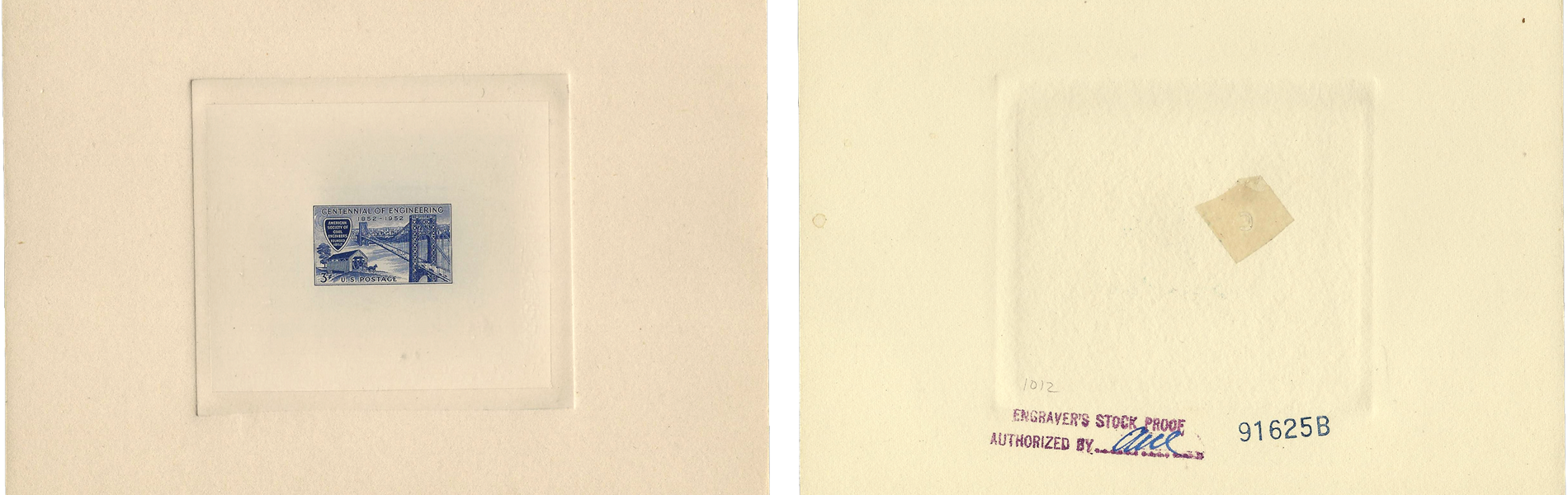

The “C” punch on the 3¢ Centennial of Engineering large die proof on wove paper and die sunk on full-size card pictured here has been taped back into place on the back (also shown), as is usually the case.

These proofs would not reach the philatelic market until the engraver had either retired or died. Jacques Schiff brought at least two of these estates to the market through his public auctions.

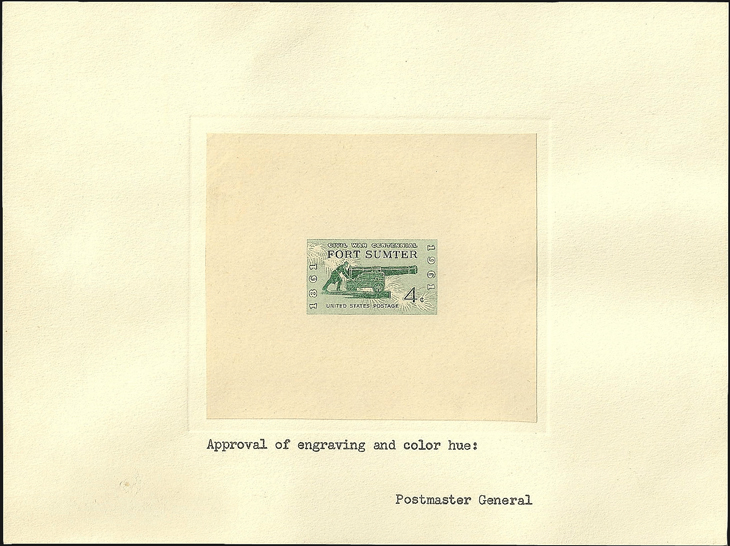

Until just a few years ago, the last 20th-century proof to fall into philatelic hands was the 1961 4c Fort Sumter die proof. However, a collector has since found a die proof for the 1962 4c Project Mercury stamp on eBay.

A 4¢ Fort Sumter large die proof on stiff yellowish bond and mounted on card is pictured nearby.

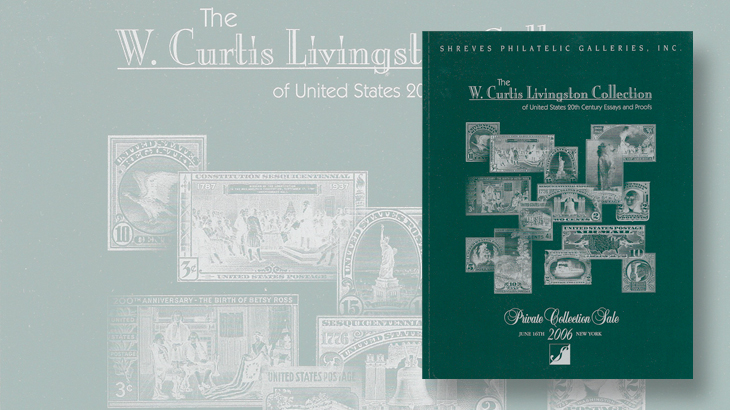

The greatest assemblage of U.S. 20th-century essay and proof material was auctioned in the early summer of 2006 by Shreves Philatelic Galleries, Inc. It was the collection of the late W. Curtis Livingston, which had been formed over a long period of time.

The Shreves catalog for this sale (shown) is still available in the philatelic literature market, and it is a great resource for the study of 20th-century essay and proof items.

The pursuit of the National Bank Note Co. to obtain patents that aimed to prevent the reuse of postage stamps will be the focus of my January 2016 column.

James E. Lee has been a full-time professional philatelist for more than 25 years, specializing in United States essays and proofs, postal history and fancy cancels. He may be reached via email at: jim@jameslee.com or through his website.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers