US Stamps

A personal stamp exhibition odyssey: from Ameripex to Pacific 97

By Ken Lawrence

As we prepare for the biggest stamp hobby event of the decade, World Stamp Show-NY 2016 that opens at the end of next month, please accompany me on my journey down memory lane as I revisit previous North American international shows I have attended. Although I had collected stamps since I was 11 years old in 1953, Ameripex 86 in Chicago was my first.

Until the 1980s, stamp collecting was a solitary pursuit for me. It mostly represented relief and relaxation from my arduous and often tense work as a civil rights activist in the Deep South. To build my collection I had saved all the stamps on my mail, asked friends to save theirs for me, and traded with collectors in other places, including people I had met through classified advertisements in Linn’s Stamp News and Stamp Collector newspapers.

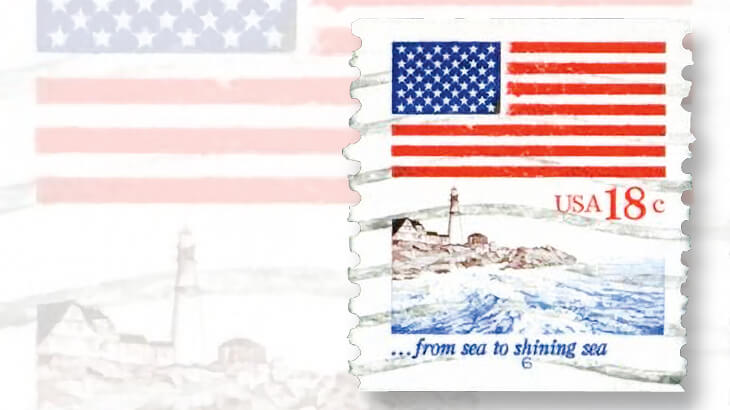

But my hobby activity dramatically changed after I got hooked by United States plate number coil stamps, which first appeared in 1981. To assemble a good collection of PNCs, I needed to make friends with other collectors from coast to coast, because stamps from specific plates were distributed unpredictably to post offices throughout the land.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

Being a writer by profession, I not only joined organizations — the American Philatelic Society; the Bureau Issues Association (later renamed United States Stamp Society); Errors, Freaks, and Oddities Collectors Club; American Philatelic Congress; and the Jackson (Mississippi) Philatelic Society — I also began writing about PNCs for Stamp Collector and Stamp Wholesaler.

After my columns appeared in those papers, Bill Welch, editor of the American Philatelist magazine, solicited an article from me titled “Collecting U.S. Is Fun Again, Newest Philatelic Rage is Plate Number Coils” that appeared in the June 1986 issue.

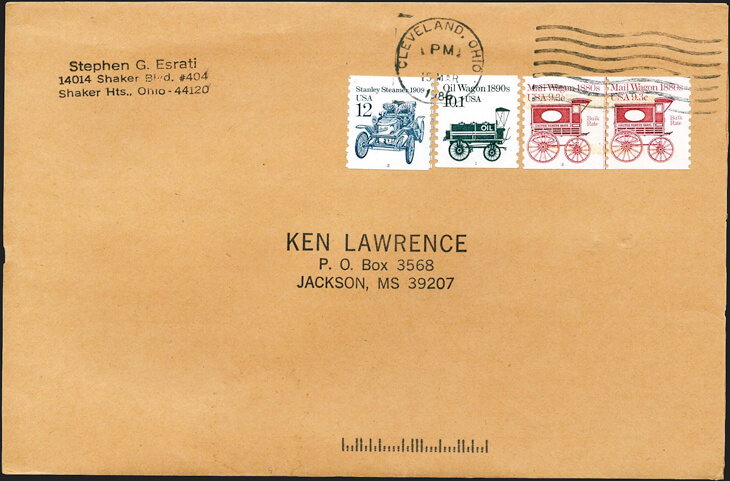

I participated in Stephen G. Esrati’s Plate Number Coil Study Group, which compiled the first Plate Number Coil Catalog, published by Esrati in several editions. Many of us decided that we ought to meet in person, and that the exhibition in Chicago would offer an excellent opportunity. We agreed to find one another at the stand of Stewart Kusinitz, a dealer who served PNC collectors and who welcomed us whether or not we made purchases.

Ameripex 86, Chicago

May 22 to June 1

Besides my personal interest as a PNC collector, I attended Ameripex as an accredited reporter for Stamp Collector, and quickly learned that the benefits of viewing legendary philatelic treasures were as important as meeting friends and correspondents who shared my collecting interests.

Under the pseudonym Rae Mader, John du Pont won the grand prix international for his exhibit of classic British Guiana stamps, which included the unique 1¢ black on magenta stamp of 1856, British Guiana Scott 13, often dubbed “the world’s rarest stamp.” From opening day to the end of the show, the frame that included that stamp drew a crowd, and was protected by a 24-hour armed guard.

The world’s most famous stamp, the 1918 24¢ Inverted Jenny error, was present in abundance, considering that only a single sheet of 100 stamps ever reached collectors. Its most dramatic presentation was in the salon hosted by Roger and Raymond Weill of New Orleans, who displayed four blocks of four owned by their clients (three intact and a fourth reconstructed). Stamp dealer Kenneth Wenger presented the so-called Princeton block (because it once belonged to Princeton University) and two single Inverted Jenny stamps at another location on the floor.

Besides viewing stamps I had only read about previously, I attended meetings and seminars related to my collecting interests: a gathering of PNC collectors, a seminar for authors and editors hosted by APS Writers Unit 30, a slide program about Holocaust mail by Illinois collector Justin Gordon, and a meeting of the Booklet Collectors Club.

Michael Laurence, editor and publisher of Linn’s at the time, invited me to join him for lunch at the exclusive members-only dining room for the show’s elite donors and guarantors. He told me all the reasons why I should leave Stamp Collector and join his “stable” of Linn’s writers. He persuaded me, and I’m still here 30 years later.

To cover my costs I had consigned several of my better stamps to Steve Ivy for sale during the show, my first participation in a commercial stamp auction. With that as my incentive, I attended not only the Ivy sale but also Robert A. Siegel and Jacques C. Schiff Jr. auctions, though I was not a bidder at any of them.

The Schiff sale was memorable for two things. The first was the original appearance of the $1 Rush Lamp stamp with inverted candlestick error (Scott 1610c). Schiff sold one stamp with irregular perforations and displayed the rest of the partial sheet on the show floor before breaking it up. Second was the sale of a cover consigned by French stamp promoter Marc Rousso, supposedly mailed by freedom fighters in Afghanistan, which Rousso valued at $2.5 million.

Subsequent events have lent irony to the juxtaposition of those two unrelated lots.

The $1 error stamp became known as the CIA Invert after the answer to a Freedom of Information request by Donald Sundman of Mystic Stamp Co. revealed that the original purchasers who had sold the partial pane to Schiff were employees of the Central Intelligence Agency. One of them had bought the stamps for use on government mail.

Later reports disclosed that the Afghan fighters against Soviet intervention in their country had been armed and financed by the CIA.

The Afghan cover was lot 1 in the sale. As Schiff called for an opening bid at the four-figure level, no one raised a paddle. Descending by hundred-dollar increments, he finally elicited a single floor bid of $300 before he could go lower.

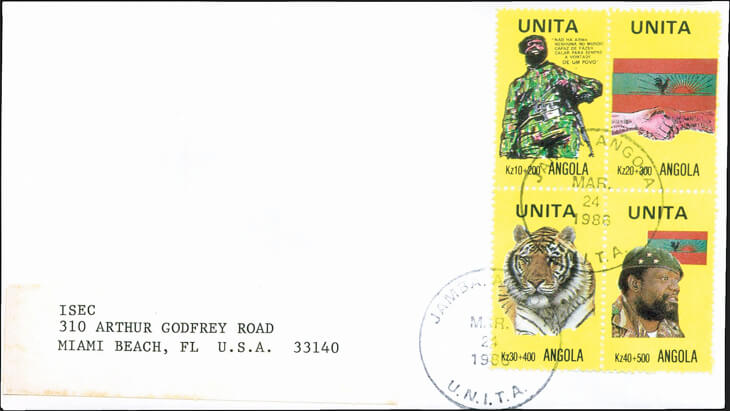

At a news conference that featured a lavish spread of hors d’oeuvres and an open bar for reporters, Rousso introduced a representative of the Angola guerrilla group UNITA, which received most of its arms and financial support secretly from South Africa and from the American CIA.

Rousso was peddling what were purported to be UNITA stamp issues, hoping that collectors would buy them at the show. When a reporter asked the UNITA man how the stamps were used on mail in the Angolan bush, the guerrilla fighter replied, “We don’t use the stamps. These are for collectors.” Few if any were sold at the show. The UNITA stamps are not listed in most major stamp catalogs, including the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue.

Ameripex was conducted under the rules and patronage of the International Federation of Philately (FIP), with prize medals to exhibitors awarded by an FIP jury. The initial costs of the show had been seeded partly by the legacy of surplus earnings from the Interphil 76 exhibition at Philadelphia, the previous FIP international in the United States, and partly by a portion of proceeds from U.S. Postal Service sales of covers flown aboard the Challenger space shuttle.

Ameripex was a profitable show, which left a larger financial legacy to seed Pacific 97 at San Francisco, the next decennial U.S. exhibition under FIP patronage. Besides being the best-attended American stamp exhibition up to that date, another Ameripex legacy was to stimulate enthusiasm for competitive exhibiting. Randy Neil and John Hotchner organized the American Association of Philatelic Exhibitors to promote that side of the hobby.

Capex 87, Toronto

June 13-21

In the golden years of FIP-sponsored international competitions, the decennial cycle included a three-year sequence that featured exhibitions in Israel, the United States and Canada, which allowed exhibitors in those three countries, many of whom shared common experiences and visits back and forth, to qualify new exhibits at one show, which in turn granted the entrant additional frames in the next show, while remaining within their familiar circles of stamp friends.

Israphil 85 at Tel Aviv had offered that opportunity for entrants at Ameripex 86 and Capex 87. Many of the same judges scored their exhibits more than once, with an expectation of consistency in awards. Japanese businessman Ryohei Ishikawa’s exhibit “The United States Stamps 1847-1869” won the grand prix national at Ameripex, followed by the grand prix d’honneur at Capex, the highest award of all.

But at Capex, to exhibitors’ dismay, inconsistency in awards was the rule in most cases. One insider who declined to be named told me, “The decision to downgrade the awards was deliberate, based on the feeling that top awards were given too freely at Ameripex.

“There was acrimonious debate [in the jury deliberations], but the U.S. contingent lost.

“The downgrading at the top led to a great inequity at the middle levels. When some exhibits were downgraded from a large gold to a large vermeil, those that normally qualify for a large vermeil were not correspondingly reduced.

“The whole psychology of judging this show was wrong. They said there are too many golds. But if you push some medals back, you have to push them all back.

“One collector whose exhibit normally gets a gold medal was emotionally shattered when he got only a large silver here.”

Another collector accepted the result in better humor: “I’ve added about 35 or 40 thousand dollars to my collection since Ameripex, and I got a lower award!”

Nevertheless I had a fine time at the show. Linn’s editor-publisher Laurence again invited me to lunch at the exclusive club for donors, joined on that occasion by Leonard Kapiloff, who owned and exhibited one of the great collections of U.S. classic stamps. Kapiloff was the publisher of Washington Jewish Week newspaper. He pressed me to write articles for him about my collection of Nazi concentration camp inmates’ letters, and Laurence asked me to do the same for Linn’s.

I turned down both requests. I explained that everything I had written about in Linn’s since I accepted the position a year earlier had increased in value as a consequence of my reporting. If I were to write about Holocaust mail, it might end up being too expensive for me to collect.

Esrati convened a meeting of the Plate Number Coil Study Group at Capex, where he passed the leadership baton to Richard Nazar. That turned out to be a disappointing move. Despite his initial enthusiasm, Nazar failed to continue annual publication of the Esrati PNC catalog, and produced only one partial revision after several years.

Anyone who had expected a repeat of Ameripex at Toronto was disappointed. Attendance was poor, and a strike of Canadian postal workers was in effect while the show was in progress. Advertised highlights, such as another opportunity to view the British Guiana 1¢ magenta, were false alarms. The exhibition was poorly publicized and poorly attended.

Between Ameripex 86 and Pacific 97, two smaller U.S. international shows enjoyed FIP auspices and awards for limited classes of competitive exhibits: PhiLitEx in New York City from Oct. 28 to Nov. 2, 1996, which awarded medals only to philatelic literature entries, and Olymphilex in Atlanta from July 19 to Aug. 3, 1996, in conjunction with the Summer Olympic Games, which was limited to sports philately.

Besides FIP-supported internationals, two outstanding exhibitions brought the whole world’s collectors, dealers and postal administrations to this country without FIP involvement: World Stamp Expo 89 at Washington and World Stamp Expo 92 at Chicago. I attended both of them.

World Stamp Expo 89, Washington

Nov. 17-Dec. 3

World Stamp Expo 89 was hosted by the U.S. Postal Service in conjunction with the 20th Congress of the Universal Postal Union, representing 170 countries, a novel experiment to showcase stamp collecting in our nation’s capital city. The original director and exhibition manager was Les Winick, who had performed those duties at Ameripex, but after the basic elements were in place, Dickey Rustin of the USPS took over and hosted the show.

Only invited exhibits were displayed at World Stamp Expo, but those classics displays took one’s breath away: Thurn and Taxis by the prince of Thurn and Taxis; Monaco by the prince of Monaco; Kingdom of Sardinia by Italian physician Dr. Saverio Imperato; Afghanistan by Horst Dietrich of Germany; South Australia by British collector John Griffiths; China by Japanese collector Meiso Mizuhara; Finland in two collections, one by Finnish businessman Christian Sundman, the second by Swedish stamp dealer Rolf Gummeson; first issues of Great Britain (which had won the Capex 87 grand prix d’honneur) by English collector Hassan Shaida; Hungary by British attorney Gary Ryan; First Issue of Netherlands by New Yorker Fred Reed, who had escaped with his stamps from Nazi Germany; New Zealand by New York airline pilot Robert Odenweller; Iceland by California televangelist Gene Scott; Cape of Good Hope by Wisconsin collector Gene Bowman; Siam by Thai expert P. Indhusophon; and Venezuela by Enrique Martin de Bustamante, the exhibit that had won the Ameripex grand prix d’honneur.

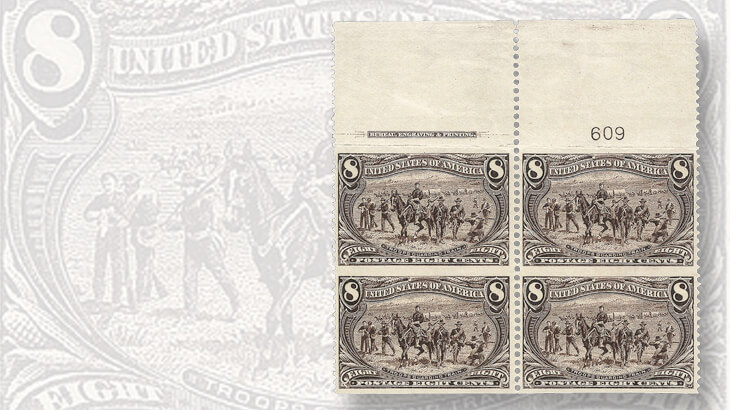

Exhibits of classic American stamps and covers included Kapiloff’s U.S. postage stamps 1842-1861; Ishikawa’s exhibit that had won the grand prix at Ameripex and Capex; One Cent 1851 plate 1 late by Chicago builder Raymond Vogel; U.S. 1861-1868 issues by Richard Drews, who was by then in charge of World Columbian Stamp Expo 92; Arizona collector and dealer John Birkinbine’s Confederate States; New Jersey developer George Kramer’s Wells Fargo; a joint exhibit of U.S. presidential franks presented by Robert Siegel, Alvin and Marjorie Kantor, and Louis Grunin; the 1869 pictorial issue by California attorney Jeff Forster; the 1893 U.S. Columbian commemorative issue by Margaret Wunsch of Arizona; First Bureau Issue by California collector Lynne Warm Griffiths; 1898 Trans-Mississippi commemoratives by Wyoming broadcast executive Jack Rosenthal; Classic Hawaii by Honolulu Advertiser publisher Thurston Twigg-Smith; Revenues by Robert Cunliffe; and Postage Dues by Rhode Island collector Cortlandt Clarke.

Only one topical exhibit was included, the spectacular “Philately and Murder” collection assembled by the Rev. Charles Fitz of New Jersey. Besides those 4,000 pages of splendid material, postal administrations and philatelic societies displayed representative examples of their material.

I doubt that anyone stayed away for the lack of an opportunity to compete. Visitors to the show had plenty of visual treats to hold their attention. In sheer philatelic grandeur it surpassed the FIP model of an international exhibition, with dealer and postal administration participation equal to the strongest FIP show.

Once again I attended a gathering of PNC enthusiasts, and another of 1938 Presidential series specialists who were beginning to organize an affinity group. During the Prexie collectors’ meeting, I sold covers from the estate of a recently deceased Mississippi collector at a spontaneously organized round-table auction. The amount his collection earned from eager bidders surprised the man’s widow, who had doubted they had much value.

World Columbian Stamp Expo 92, Chicago

May 22-31

This exhibition celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage to America, and by implication the centennial of the 1893 Chicago world’s fair. By the time I attended World Columbian Stamp Expo 92 in Chicago, I had been elected to the APS board of directors as an at-large member. APS held its annual spring board and membership meetings to coincide with the show, which in those days meant that elected leaders’ travel and lodging were paid by the society.

In many respects this exhibition duplicated the best of Ameripex, but without the FIP competition and jury. Once again, the bourse included dealers and postal administrations from around the world. Once again, specialty societies held meetings and seminars, major auction firms found new owners for rare stamps and covers, the schedule included dedication ceremonies for new stamps, and special cancels pictured related subjects.

Unlike World Stamp Expo 89, World Columbian Stamp Expo 92 did host competitive exhibits at the national level, part of the annual World Series of Philately circuit. The annual Compex (Combined Philatelic Exhibition of Chicagoland) event added activities sponsored by each of its federated member clubs.

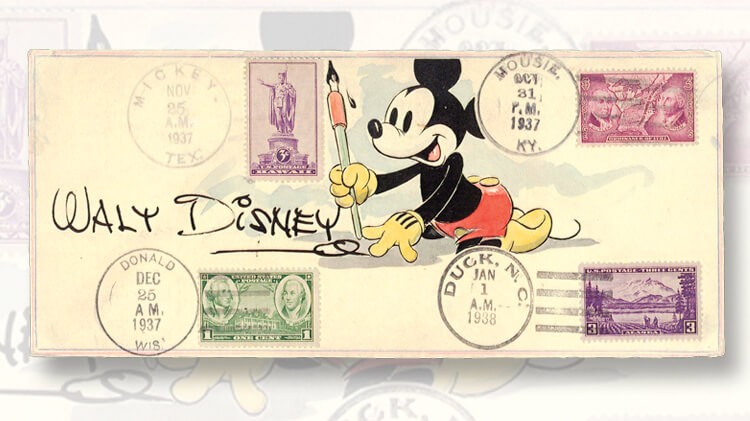

For the first and only time, I entered my 10-frame topical exhibit titled “The Sun Never Sets on Mickey Mouse: Walt Disney’s Worldwide Empire” in the national competition. The jury awarded a vermeil medal, which qualified me to become an apprentice judge. Thereafter I showed my Disney collection often, but never again competitively.

The show’s court of honor was not as regally decked out as the one at World Stamp Expo 89, but I found some of the exhibits more entertaining and one of them more impressive. In the latter category, Jack Rosenthal’s 20-frame display of stamps, stamped envelopes, covers, coins, ribbons, tickets, and other memorabilia of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was the best I had ever seen. Combining that experience with his Trans-Mississippi exhibit at World Stamp Expo 89, I resolved to become an expo collector myself.

One episode at the Chicago show had greater significance afterward than anyone could have predicted at the time. The most controversial United States stamp — the 24¢ Winfield Scott stamp on ribbed paper, printed between 1873 and 1875 by the Continental Bank Note Co. — appeared in the court of honor, courtesy of its owner, Eraldo J. Magazzu.

In 1978 the Philatelic Foundation had certified Magazzu’s stamp as Scott 153, the National Bank Note Co. printing. But scholars had shown that ribbed paper was a trait of Continental Bank Note Co. printings, not the 1870 National Bank Note Co. issue. After Bank Note issue specialists at Ameripex had advised Magazzu to resubmit his stamp to the Philatelic Foundation based on a more thorough study and documentation, he received a revised opinion that his stamp was indeed the elusive 24¢ Continental (Scott 164). At present, that stamp is unique, now owned by bond tycoon and champion exhibitor William H. Gross, who has the only complete collection of 19th century United States stamps.

World Columbian Stamp Expo 92 was a financial success. For many years afterward, the organization donated money from the earnings to worthy philatelic organizations and causes. While the Washington and Chicago non-FIP international exhibitions were proving that positive results could be achieved without the federation’s blessing, show organizers who remained in thrall to the FIP were finding its requirements increasingly onerous and difficult to meet.

In a 1995 paper titled “The Philosophy of International Exhibitions” presented to the Philatelic Congress of Great Britain, Kenneth Rowe, a leader of the Royal Philatelic Society of Canada, set forth the challenges:

Philately is probably the most organized of all the collecting hobbies in the world, and is in real danger of becoming over-organized and rigid. …

A modern international exhibition is a very complex operation that often is improperly understood. The integration of many diverse groups is made doubly difficult by the fact that each group approaches the event with different, and sometimes unrealistic, expectations. …

Developments during the last fifty years have changed our exhibitions from simple “show and tell” affairs to the massive, expensive, and fiercely competitive events that we now take for granted. …

In spite of wishful thinking in some quarters, people cannot be taught to be stamp collectors.

This sobering fact is apparent in the declining memberships of both local and national federations. The peak period is now behind us, and philately is now in competition with the other collecting fields for that small section of the population which has the acquisitive instinct.

It follows, therefore, that the outlook for successful international exhibitions, at least in the West, is not rosy. …

The other cause of unhappiness is the increasing number of incursions by the Federation Internationale de Philatelie (FIP) into the control and administration of international exhibitions. …

At this period the costs of obtaining FIP patronage make it impossible to consider putting on an international exhibition without significant financial support from the national post office. …

It is, therefore, apparent that the FIP depends for its existence upon the continuation of the current patronage system. In spite of this obvious fact, the FIP is not making rules to make it easier for a member federation to hold an international exhibition but is, in fact, making it more difficult and certainly more expensive. …

It obviously is time for the FIP to downgrade its regulatory efforts before they become counter-productive . …

The next two North American exhibitions would affirm Rowe’s observations with a vengeance.

Capex 96, Toronto

June 8-16

As an apprentice member of the FIP philatelic literature jury and an advisor to the expert group for the philatelic jury, I had a different perspective at Capex 96 from my previous participation in international exhibitions and less opportunity to spend time at the bourse or at society meetings and seminars.

The jury at that show was haunted by the reputation of the Capex 87 jury as harsh and cruel. F. Burton Sellers, leader of the U.S. delegation, assigned me the task of checking each scoring team’s preliminary results for our country’s exhibits with their previous scores and medal levels in both national and international competition, and to report to him any discrepancies.

At one point during the deliberations, Rowe obtained permission from FIP president D.N. Jatia to allow me to explain to the jury how to evaluate 20th century U.S. exhibits, an exceptional responsibility for a mere apprentice, but a stratagem Rowe hoped would forestall any attempts by judges from other countries to demean them.

Jatia also assigned me to apprentice in the airmail class even though I had not exhibited airmail, on the understanding that I had studied the standard references and had a significant collection of airmail postal history. Not really kosher, but a splendid learning opportunity that has served me well ever since.

In other respects I enjoyed Capex 96 much more than its 1987 predecessor, and heard no complaints comparable to the earlier ones, even though some exhibitors were inevitably disappointed with their awards. But despite far superior organization, management and publicity, Capex 96 was a financial failure, as Rowe had privately predicted. It was the last FIP world stamp exhibition held in Canada, bringing an end to the Israel-Canada-United States cycle.

Another stamp show in 1996, not an international exhibition, further revealed the unfulfilled potential of the FIP system. The Collectors Club of New York observed its centennial with Anphilex 96 held at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. It was not a big show, but the world’s elite collectors and dealers participated. Even members of modest means, including me, were invited to exhibit single frames. Mine was an exhibit of classic United States first-day and earliest-use covers.

But the most memorable Anphilex 96 feature was Robert Zoellner’s complete exhibit of United States stamps on Scott album pages, the way nearly all of us collected stamps most of our lives, which competitive exhibiting rules all but forbid to be shown.

Pacific 97, San Francisco

May 29 to June 8

Expectations were high for the Pacific 97 world stamp exhibition to match or exceed the success of Ameripex 86. The 11-year span between the two allowed the show to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the first United States postage stamp issue, and to feature it prominently in the splendid “Monte Carlo” court of honor exhibit, subsequently revealed to be owned by Gross.

As a surprise innovation, the 1997 edition of the American Philatelic Congress Book, edited by Barth Healey, doubled as thePacific 97 Handbook, including a large selection of scholarly articles related to the themes and displays at the show. Congruent with the stamp sesquicentennial was George W. Brett’s documentary report, “Updating the U.S. 1847’s on Their 150th Anniversary: Beginning, Production, Ending.”

Appropriate for the first U.S. international stamp show on the Pacific Coast (indeed, the first one located west of the Mississippi), the American Air Mail Society contributed “The Last Flight Out: Seven Pan American Clippers on the Eve of Pearl Harbor,” illustrated by some of the greatest covers carried on those flights. Court of honor frames hosted Kenneth Kutz’s “Gold Fever” philatelic exhibit.

My Walt Disney exhibit, also suited to a West Coast audience, was invited as a special noncompetitive display, the final outing before I sold it after five years of frequent guest appearances at World Series of Philately events.

George Kramer won the grand prix national with “Across the Continent — mail across the American continent before the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869,” which included the greatest Pony Express rarities, the first time a U.S. postal history exhibit had earned that honor.

Two collectors from Thailand won the other top prizes: The international went to Pichai Burenasombate for “Classics of Great Britain,” and the grand prix d’honneur went to Surajet Gongvatana for “Siam.”

I was a vice president of the APS that year, which held its spring meeting during the show. Although everyone I met there enjoyed the experience, insiders seemed restrained by unfocused apprehension that turned out to be well-founded. The organizers had overspent the exhibition’s income by $480,000.

All the seed money bequeathed by Interphil and Ameripex was lost, as well as large grants from World Columbian Stamp Expo and Westpex. Patrons’ guarantees were called in to cover the shortage, the first time that occurred at a U.S. international. Eventually additional donations by the Postal Service and major philatelic organizations paid off the outstanding debts, but the future of U.S. internationals was in doubt.

Causes of the disaster were never clearly explained, but part of the reason was the FIP burden that Rowe had predicted and part was mismanagement. With no legacy to pass on, many observers wondered whether the next international scheduled for the United States could succeed. Washington 2006 was already being organized. Next month we’ll resume with my report on that experience.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers