US Stamps

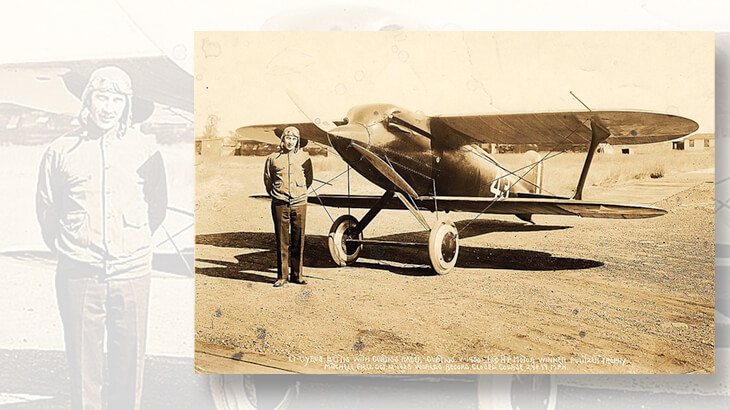

Airmail pilot known as fastest man on Earth in 1926 defeated by Pennsylvania hills

By Kathleen Wunderly

The Pennsylvania mountains that were the nemesis of pilots from the earliest days of United States airmail claimed another aviator 90 years ago this month.

Cyrus K. Bettis was born Jan. 2, 1893, at Carsonville, Mich. After high school and a business course in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, he worked in Fenton, Mich., from 1913-1916 as manager of Exchange 26 of the Michigan State Telephone Co.

Young Bettis seems to have settled into a stable white-collar career, but then made a life-changing choice by taking lessons at the O.E. Williams School of Aviation in Fenton. On Feb. 2, 1918, he became a flying cadet in the Army Aviation Section, Signal Corps, and graduated from the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Bettis completed flight training in September 1918 at Call Field, Wichita Falls, Tex., and then did duty on the Mexican border and in the Philippines. He rose from private in 1918 to first lieutenant by 1920, and in 1923 was transferred to Selfridge Field, Mount Clemens, Mich., base of the army’s elite 1st Pursuit Group.

Bettis now was skilled enough to be chosen to represent the Army in air races. On Oct. 4, 1924, he won the John L. Mitchell Trophy Race in Dayton, Ohio.

The Mitchell race was established in 1922 by Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell, in honor of his younger brother who was killed while flying with the 1st Pursuit Group in World War I.

Bettis flew an average 175.41 mph to capture the 1924 Mitchell trophy, a record that held through the next six races. He used the airplane that, by the mid-1920s, had begun to dominate U.S. air racing: the Curtiss R3C, a single-engine biplane built as a landplane (R3C-1) and a floatplane (R3C-2).

Flying for the Army, Bettis used the R3C-1 again the following year, in the Pulitzer Trophy Race, then considered the top event of the national air race circuit.

New York newspaper magnate Ralph Pulitzer established the race in 1922 to encourage the development of faster landplanes. The trophy went to the pilot and plane with the fastest time during four laps over a closed course.

On Oct. 12, 1925, Bettis, representing the 1st Army Pursuit Group, flew an R3C-1 racer pursuit plane to win the sixth (and last) Pulitzer Trophy Race. Bettis won at an average speed of 248.99 mph over a triangular course of 124.27 miles.

The Boston Herald reported on the race in its Oct. 13, 1925, issue, “Covered with grime and glory, with his plane shooting flame in the gathering darkness, Lt. Cyrus K. Bettis, army ace, today won the Pulitzer trophy race feature of the national air races, broke the world’s speed record of 243.67 miles per hour for a closed circuit course, and established a new record of 248.99 miles per hour.”

On the same date, The New York Times wrote, “It was piloted by Lieutenant Cyrus K. Bettis, contesting for the army, a quiet, retiring little man with an iron nerve and a knowledge of flying which enabled him to get every ounce of power out of his motor.”

Bettis actually was disappointed with the race results, as he had done better than that in the trials and had predicted a speed of 270 mph in the contest. Nevertheless, Bettis and the R3C-1 were the fastest pilot and aircraft in the world in 1925.

Adding to his fame, Bettis was awarded the Clarence Mackay Army Aviation Trophy in 1926 for outstanding aerial performance in 1925. This prize was shared with Lt. James H. Doolittle, winner of the 1925

Schneider Cup in a Curtiss R3C-2 seaplane.

In 1926, Bettis was still stationed at Selfridge Field with the 1st Pursuit Group, but that May he was sent to Camp Anthony Wayne, a model military camp of 1,000 soldiers set up at the Sesquicentennial International Exposition in Philadelphia.

Near the end of August, Bettis and lieutenants Luther S. Smith and John J. Williams prepared to fly back to Selfridge Field to have their planes tuned up, after which they would return to Philadelphia for the National Air Races, Sept. 4-13.

On Monday morning, Aug. 23, the three aviators flew out as a group, on a route taking them across the center of Pennsylvania and its Allegheny Mountain range. Part of the route was the same as that followed by the first airmail pilots flying from Long Island, N.Y., to Cleveland, Ohio, with a stop at the airfield in Bellefonte, Centre County, Pa.

Part of the Appalachians, the Alleghenies run for more than 500 miles northeast to southwest across Pennsylvania and into Maryland, West Virginia and Virginia.

The Alleghenies have an abundance of long, narrow ridges that vary widely in height, from 440 feet to 2,775 feet.

This rough terrain in the middle of Pennsylvania exaggerates weather conditions, encouraging low-lying fog as well as thermal updrafts causing unexpected wind gusts. Abrupt and dramatic changes in barometric pressure also are common. Conditions vary wildly over distance, with one valley deeply fogged in and another perfectly clear only a few miles away.

In the early days, with little instrumentation beyond a compass and a primitive altimeter, fliers typically navigated by visual observation of the horizon and natural or manmade features, such as waterways, topography, canals and buildings.

Until the invention of a more sophisticated altimeter in 1928, relying on the altimeter while flying in the mountains was risky business, when one-tenth of a point of that unstable barometric pressure would equal 100 feet on an altimeter, and mean the difference between clearing a mountaintop or flying right into it.

Late August, with hot days and quickly cooling nights, is a prime time for dense and lingering fog in the Alleghenies, and Smith and Williams lost sight of Bettis as the three planes approached the Lewistown area, about 160 miles west of Philadelphia. Smith managed to stay on course and reached Selfridge in late afternoon. Williams landed at the Bellefonte airfield in early afternoon, then continued on to Selfridge.

Bellefonte was chosen in 1918 by the U.S. Post Office Department as the site of the only scheduled fuel and maintenance stop in Pennsylvania on the first U.S. westward airmail route. An airfield was quickly built in late 1918, and a second, larger field was constructed in 1925 to accommodate the bigger aircraft and ground lighting needed for the transcontinental night mail.

When Bettis did not arrive at Selfridge on Monday, Smith and Williams flew back toward Bellefonte while other planes came from Philadelphia. They conducted aerial searches on Tuesday and Wednesday, to no avail.

Fog and geography had accomplished what neither military flying nor high-speed racing had done, causing the ace aviator to crash. The wreck happened on Jacks Mountain, about 30 miles southeast of Bellefonte, near the part of the range known as the Seven Mountains.

Thinking he had cleared the mountain in the dense fog, Bettis had sideswiped a tree on a hillside, hit the ground, bounced and then hit the ground again.

Mail pilot Charles H. Ames had a similar accident on Oct. 1, 1925, on a night flight from New Jersey to Bellefonte, with a fatal result. In heavy fog, Ames flew straight into the side of a mountain a few ridges and valleys north of where Bettis came down. Airmail service investigators concluded that variations in barometric pressure caused Ames’ altimeter to give a false reading that led the pilot to believe he was flying 100 feet higher than he actually was.

Bettis crashed a little after 1 p.m. on Monday, Aug. 23, and was knocked unconscious. He awakened a few hours later, still strapped into his seat but with his aircraft in pieces around him, the wings crumpled, and the motor and propeller and radiator scattered in various directions. Those who had visited the site of both the Ames crash and the Bettis wreck said that the latter was the worse of the two, though amazingly sparing the pilot’s life.

Bettis’ injuries included his left leg broken above the knee, broken nose and jaw, cuts and bruises, and surely internal injuries as well. Recounting the story later to a New York Times reporter, Bettis said that he hoped the wreckage would be visible to the search planes he could hear overhead. The trees were in full leaf, however, and the remains of the plane were well hidden. Bettis had no food, but managed to catch some of the drizzling rain in his hands.

Some 27 hours after crashing, he decided he would not be found alive if he did not try to save himself. Thus, the “quiet, retiring little man with an iron nerve” set out around 4 p.m. on Tuesday, crawling on hands and one knee, dragging his broken leg through the dense thicket and over the glaciated rocks. That evening he was close enough to a road to hear traffic, and made it to the road around 9 p.m. before collapsing.

Bettis woke at dawn on Wednesday and resumed crawling, until found by two teenage boys who were berry picking. One of the boys ran to the cabin and summoned his mother. She then went to the nearest telephone, which was not very near, and brought help in the form of two state highway workers with a vehicle in which to transport Bettis to the hospital in Bellefonte.

The aviator had crawled for more than six hours through at least three miles of heavy brush and rocks.

Dr. David Dale, a surgeon in WWI, worked on Bettis at the Bellefonte hospital until two military surgeons from Carlisle and Washington, D.C., arrived later on Wednesday. They pronounced Bettis to be in surprisingly good condition and decided to transport him to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, though the flier asked to stay in Bellefonte.

A Douglas C-1 transport plane arrived in Bellefonte on Thursday morning from Bolling Field, Washington, and Bettis, swathed in bandages, was taken by ambulance to the local airfield, where the plane took off at 12:42 p.m.

Several news stories — and there were many nationwide because Bettis was a celebrity from his racing triumphs — mentioned that because their patient could not wear a parachute on the flight, the pilots and medical officers refused to wear one.

Physicians at Walter Reed felt that Bettis had “a splendid chance for recovery,” but meningitis set in on Aug. 31, and the air ace died at 9:05 a.m. Wednesday, Sept. 1, 1926, nine days after the crash in the mountainous wilds. He was 33 years and 8 months old. His body was returned to Port Huron, Mich., where his parents lived.

With a military escort, and planes from Selfridge Field overhead, Bettis was buried in Lakeside Cemetery in Port Huron.

“Affectionately known as ‘Cy’ throughout the service, Lieut. Bettis’ death is a severe loss, both to his many friends and the science of flying, in which he had contributed an uncanny skill for manipulation of light and sensitive machines,” the Evening Star in Washington, D.C., wrote on Sept. 2, 1926.

Shock and sorrow were widespread, as America’s mail pilots and military aces were superstars of that time, with well-publicized feats.

A Pennsylvania tribute to the brave and tenacious airman quickly came from Pittsburgh, where officials announced that the Pittsburgh-McKeesport Airdrome would change its name to the Bettis Airfield.

The airport had opened in June 1925 and was the first major airstrip in the Pittsburgh area. It was formally dedicated to Bettis in ceremonies on Nov. 14, 1926.

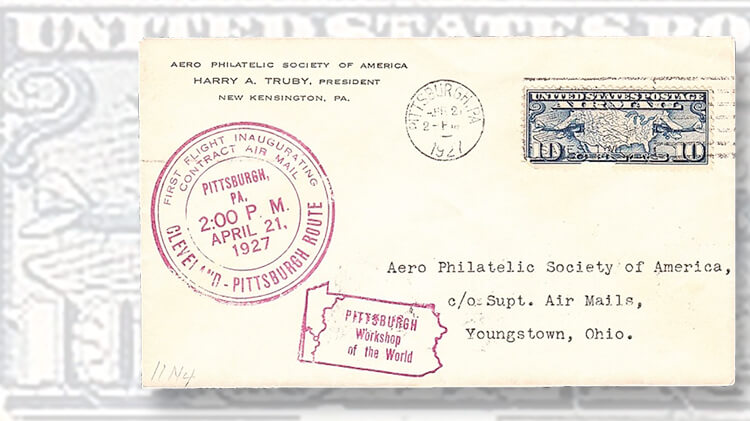

Bettis Field was the hub of the first airmail route to Pittsburgh: Contract Air Mail Route 11, connecting Pittsburgh and Cleveland and inaugurated on April 21, 1927. A first-flight cover is shown nearby.

A few months later, on Aug. 3, an estimated 100,000 people massed to watch Charles Lindbergh land in the Spirit of St. Louis, one of his 78 stops on his victory tour of America following his solo trans-Atlantic flight in May.

Bettis Field is long gone, replaced in 1949 by a government facility that designs and develops nuclear power for the U.S. Navy. The new occupants did retain the historic name; the site is called the Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory, perpetuating the memory of one of the most talented aviators in the world in the 1920s.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 3 PMProspectus available for Pipex 2025

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 2 PMGratitude for Denise McCarty’s 43-year career with Linn’s

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 12 PMWorld’s first butterfly topical stamp in strong demand

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 3 PMRoyal Mail’s Oct. 1 definitive meets new international standard rate