World Stamps

The story behind the airmail collection of one of the hobby’s leading ladies

By Ken Lawrence

Events of recent months have focused public attention on the world’s most famous error postage stamp, the United States red and blue 24¢ Curtiss JN4H airmail stamp of 1918 with inverted center, Scott C3a. Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries launched the InvertedJenny.com website on May 14, a digital encyclopedia about the origin and discovery of the single pane that comprised 100 examples of the error and the subsequent history of each stamp.

Siegel’s president Scott R. Trepel arranged to display an original flightworthy Curtiss Jenny biplane, the aircraft pictured on the stamp, at the World Stamp Show-NY 2016 international stamp exhibition in May and June. At his firm’s May 31 Rarities of the World sale during the show, he sold the best-centered example, the stamp from position 58, for a record price of $1,351,250, including the 15 percent buyer’s premium. One day later, Schuyler Rumsey’s auction sold the position 8 stamp, long ago reperforated to remove the original straight edge at the top, for $218,500.

Another Inverted Jenny, position 76 from the block of four once owned by Ethel B. McCoy, which had not been seen since it was stolen while on display at a stamp show in 1955, was recovered by the American Philatelic Research Library during the show. Donald Sundman, president of Mystic Stamp Co., paid a $50,000 reward to Keelin O’Neill, the young man from Northern Ireland who found the stamp among items he had inherited from his grandfather.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

These developments, widely reported in major media outside hobby circles, reminded me of another Inverted Jenny once owned by a leading lady of our hobby that deserves to become better known, the position 32 stamp at the British Library in London, pictured above.

In his 1986 Amos Press book Jenny! George Amick had reported, “No record. Illustration of stamp with characteristics matching those of position 32, centered slightly to left and bottom, appeared in the 1932-33 Resume of H.R. Harmer Ltd., London, … Same stamp is illustrated in the book Stamps of Fame by L.N. and M. Williams (London, Blanchford Press, 1949).”

A January 1992 Philatelic Foundation publication, The Inverted Jenny: A Photographic History, included a picture in the position 32 location (second stamp in the fourth row) but its whereabouts was unknown. Yet as Amick wrote in the Sept. 16, 2013, Linn’s, it “turned out not to have been lost at all.”

The Autumn 2007 issue of British Library Philatelic Collections Newsletter included a color photograph of the stamp in a review of an 18-volume “collection of airmail rarities formed by Mrs Augustine Fitz Gerald,” donated to the British Museum in 1947 and later transferred to the library.

From that image I was able to plate the stamp as position 32. Michael Schreiber reported my plating in the Dec. 17, 2007, Linn’s (page 2), “Jenny Invert: stamp from position 32 in British Library.” Recalling that episode prompted me to learn more about FitzGerald (as she and her husband spelled their name) and her collection. Here is their story:

The Wyndham sisters and their stamp collections

Sybil Mary Winifred Wyndham was born in 1868 at Lewes, Sussex, England. Her older sister, Ethel Mary Wyndham, had been born five years earlier. Both Wyndham sisters came of age during the Victorian formative years of our hobby and both collected stamps.

As a young woman Sybil Wyndham was an operatic prima donna. She acted and sang at the Savoy Theater in London, home to Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and on the European continent. James C. Duff, the producer who introduced Gilbert and Sullivan to America, brought her to this country to tour with his comic opera ensemble in the spring of 1894 and to star at his Olympic Theater in New York during the summer season.

A critic who reported on the opening performance ofGilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe on Broadway wrote, “Miss Wyndham, the soprano, is a handsome woman with a voice of excellent quality. Her acting and appearance last night were at all times in accord with the spirit of the part.” She played the role of Phyllis, the object of every man’s desire around whom the drama occurs.

Although still known on stage as Sybil Wyndham, she had married Augustine FitzGerald in March 1894. He was a Yale alumnus; according to A History of the Class of ’82 Yale College, they “married at Florence — the ceremony being performed at the British consulate, the English Church, and the Italian Municipality.”

Sybil’s singing and acting career appears to have ended after the 1894 summer opera season closed at New York. Afterward she and her husband lived most of the time at Paris, but they also kept residences in St. Moritz, Switzerland, and Middlesex, England, and were frequent travelers to other lands.

Tessa, as Sybil’s elder sibling was known, married British civil servant Robert Arbuthnot in 1899. Both women spent much of their adult lives as residents of continental Europe, Tessa in Italy, and Sybil in France. Both became prominent philatelists. Sybil died in February 1964; Tessa, in September 1965.

In his obituary of Tessa Arbuthnot, Robson Lowe wrote that she “bought her first album from Stanley Gibbons in 1874. Her collection was world-wide and nearly all of the stamps which she bought as a child for pence are treasures today. However, the recollection which remains most vivid to us is the large number of collectors she had met personally during her travels before World War II and the envelopes and cards addressed to her from unusual places half a century or more ago.”

In contrast to her sister’s interest in all the postage stamps of every country, Sibyl FitzGerald focused almost exclusively on airmail, beginning with the earliest examples. A woman of culture and sophisticated taste, she formed one of the greatest specialized airmail collections of all time.

Sybil and Augustine FitzGerald, a creative couple

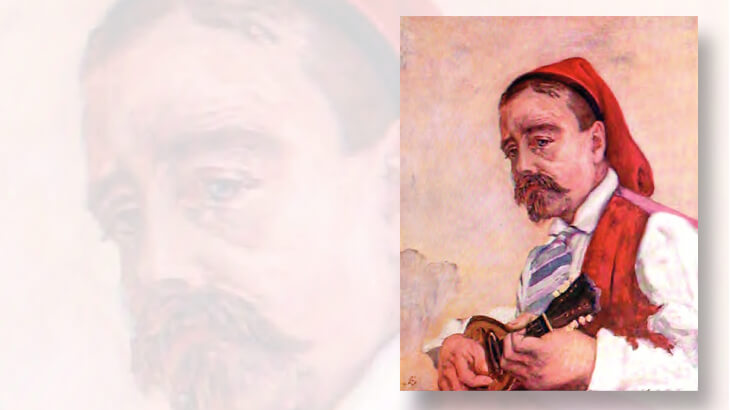

The FitzGeralds collaborated in writing two highbrow travel books, with Sybil as the author and Augustine as the illustrator. A passage from their 1904 book Naples, illustrated by his painting of a musician reproduced here, echoes insights she probably had absorbed when she trained to become a performing artist:

Imagine this scene on a starlit autumn night, the sea bright as polished crystal. Not a single cloud is in the sky, save that beautiful column rising like a stone pine above Vesuvius. The city and all around the bay is a glitter of lights. On the roads, white with dust, not less than some twenty thousand gaily-dressed men, women, and children are moving along, tired, overheated, but light-hearted happy. It is the night of their greatest Festa [festival of the Madonna of Piedigrotta, for which new songs are composed every year], a festa which will last with song and dance far into the morning hours! …

Song and dance must be heard and seen together to be appreciated. The blue sky must be overhead; the faces of the singers must be olive-tinted and dark-eyed! … For long past there has existed here in the South a school of song which is quite unique; into it any introduction of orchestration is fatal. The mandolin, the guitar, the castanets — these are their natural instruments; and, strange as it may seem to critics, the rich and untrained voice, when accompanied only by these simple instruments, has a wild charm of its own, quickly lost in the midst of a more complicated orchestra. …

Only at Sorrento the tarantella [a traditional folk dance of southern Italy] still keeps something of its old charm. Of an evening the dancers take their places in the open courtyard of the hotel. Their background is a garden of orange and lemon trees and flowers, the breath of which perfumes the air deliciously. The stars twinkle in the dark blue sky, and the whole scene is lovely and poetical. … Never do we hear the cheaply sentimental note; and as to the comic songs, although coarse and often full of double meanings, they have not the common vulgarity of our music-halls.

Returning to Sorrento in a later chapter, she summed up these sensations in a single sentence: “A summer’s night at Sorrento is intoxicating in its charm of sight, of sound, and of scent.”

In the FitzGeralds’ 1905 book In the Track of the Moors: Sketches in Spain and Northern Africa, after cautioning the reader that Spanish national pride sometimes “rouses a contempt for whoever confesses ignorance of anything Spanish,” she advised:

Let the stranger who longs for a responsive smile and alert intelligence turn to the children of Spain, who seem so full of that pathetic vivacity which leads to no goal; let him get a child-guide who will point him out everything, good or bad, fair or foul, with lively impartiality, continually looking up at him with large dark eyes in which but the shadow of settled gloom has as yet penetrated. … He will guide as though he were the man, and his follower but a helpless child … his alertness roused by the firm belief in his companion’s complete ignorance of everything under the sun.

Do modern Google searches or guidebooks serve as well to pique the traveler’s thirst for exotic cultural adventure or to suggest such sensible solutions to common tourists’ annoyances? Augustine’s illustrations highlight and punctuate Sybil’s insights throughout both books.

Besides visiting places in Europe and North Africa, the FitzGeralds crossed the Atlantic on several occasions. In December 1914, they and their 19-year-old daughter Alida were passengers on the RMS Lusitania’s trip from New York to Liverpool, five months before a German submarine sank the liner.

Augustine FitzGerald died in August 1930. Sybil kept her residence in Paris until the German conquest of France in 1940, when she departed in haste for England.

Enduring FitzGerald airmail lessons

Sybil FitzGerald’s narrative about the origin of her airmail collection is as captivating to this writer as her travel writing was to discerning tourists more than a century ago. She wrote:

Every collector, I imagine, looks back with interest on his first possession. The beginning of this collection was small indeed. A single Russian airstamp of which nothing was known (Champion’s wonderful little catalogue had then hardly seen the light). It cost 75 francs and was sent from a small bookstall on the Riviera which included a few philatelic items among its second-hand books. “It is very rare,” wrote the sender. “Tres rare et tres interessante. If you do not keep it, I pray you will seal it in returning it to me.” Not for many years was it listed, and then only for some trifling sum.

A more serious choice was the set of semi-official stamps of Rouen, 1922 — a first enlightenment into all that the words “variety” and “error” can mean in a catalogue of the Air Posts. Then came the first rarity, a French Guiana black on blue Mercury’s head. This cost something round about 450 francs. To this day, the sight of the little label brings back the sensation of excitement with which it was borne away from the stamp shop, even to the sound of the rattling coloured beads over the door tinkling down as the proud possessor passed through them from the cool interior into the hot sunshine.

Long before she offered to donate her collection for professional preservation and public appreciation, FitzGerald contributed to the advance and uplift of philatelic culture by translating important articles by the French aerophilatelist Louis Morel into English.

In her translation of Morel’s 1926 monograph “Undesirable Air Covers,” published by the Aero Philatelic Society of America, the author reported that the incidence of forgery had increased with the growth of airmail as a collecting interest.

He discussed how to avoid being duped by forged surcharges, fake and favor cancels on covers that had never flown, fake cachets, pseudo air covers (covers bearing genuine airmail stamps, cancels, or cachets as souvenirs of events, but never intended for flight), and superfluous air covers such as: “the smallest village fete has been the pretext for air post, … the tail of every kite carries letters, and children’s toy balloons are nothing now without the addition of an air mail.”

In FitzGerald’s translation of “The Future of Aero-Philately,” published in the September 1926 issue of Aero News, Morel countered the habit of centering a collection on airmail stamps first, then on souvenir covers, with this more progressive counsel: “Pigeon, balloon, aeroplane — the manner of transmission is of no importance, providing it be aerial. Postage stamp, vignette, label, cancellation, or handstamp, every mark of destination by air post service, if legitimately issued and applied, is of equal interest. Official, or semi-official, every flown cover is fair, providing it proceeds from some public service realizing a need, or from some public sentiment.”

Today those sentiments seem prosaic, but to the first generation of airmail enthusiasts they represented uncommon wisdom. FitzGerald herself took them to heart in her personal approach to collecting, as is evident in her Feb. 5, 1942, letter to the British museum:

I am venturing to write and ask you whether the British Museum would care for the donation of a very valuable Air-Mail Collection. It is a ‘pioneer’ collection, composed of the earliest curiosities, stamps, letters, etc., and has, as far as possible, avoided the inclusion of the popular items generally found in the collections exhibited and sold. This Collection has never been exhibited, and publicity has never been sought for it, but it is not unknown among aerophilatelists. … In these uncertain times one is anxious to preserve collections of value in what safety may be possible and I realize that were mine in my possession at the time of my death, it would be liable to dispersion, or loss, and its value as a whole would be completely lost. If this offer is of any interest to the Philatelic Department of the British Museum I should be very glad to hear from you. … If no interest I must apologize for troubling you in this matter.

James A. Mackay quoted her letter in a comprehensive two-part review, “The Fitzgerald Collection,” in the August and September 1965 issues of Philately. His article is equivalent to a finding aid in today’s archival practice. At the time he wrote, Mackay was assistant keeper in the museum’s department of books. He continued:

The Museum was very pleased to have the offer of such a fine collection, its finest philatelic acquisition for fifty years. Five years elapsed, however, before it passed into the hands of the Museum. Under wartime conditions the other philatelic collections had been locked in an underground vault for safety and bomb damage to the galleries meant that some time passed before the exhibition rooms could be opened to the public again. In May 1947 Mrs. Fitzgerald deposited her collection in eighteen volumes at the Museum. …

Unfortunately Mrs. Fitzgerald, who had resided for many years in France between the wars, had to leave that country hurriedly in June 1940 and thus lost the first volume, containing the airmails of the United Kingdom.

Consequently the British section is very weak, being confined to a few pieces that she acquired during and immediately after the Second World War.

(Mackay was later disgraced, convicted of theft from the museum’s philatelic collections, and repeatedly in trouble with publishers as a plagiarist, so most writers, including me, use his publications as sources reluctantly. In this instance his article provides the best available overview of the FitzGerald collection.)

Early airmails from Italy chronicled 1957-1958

A series of four articles by Leonard H. Harris in 1957 and 1958 issues of Italian Philatelist titled “The Fitz Gerald Collection” indicates the scope of Sybil FitzGerald’s philatelic achievement. Despite his title, Harris covered only the parts from Italy.

The earliest item is an 1846 illustrated advertisement from Venice for the Prima Barca Aereo-Postale Nominata L’Aquila (the first air-post ship named The Eagle), regarded as the earliest reference to air transport of mail. The airship is pictured as a huge gas-filled sausage powered by oar-like paddles, guided by a rudder and equipped with a parachute and an anchor, with a crew riding below the balloon in a suspended gondola.

Next are an autographed entrance ticket to Luigi Piani’s 1852 aeronautical display at Bologna; a picture postcard of a balloon carried on an April 26, 1904, balloon ascent, franked with a 2-centesimo stamp canceled at Rome on that date, addressed to Naples; souvenirs of other balloon ascents; cards from the first international air meeting at Brescia in 1909; and rare covers from pioneer powered flights.

Italy issued the world’s first government airmail stamps, which “are represented in great detail,” Harris wrote, in unused condition and on rare flown cards and covers. An unissued 1922 stamp prepared by the Italian post office at Constantinople for a planned flight from Bucharest to Paris is “probably the rarest Italian semi-official item,” one of three recorded. Italy’s Arctic flights are fully represented as are Italo Balbo’s 1930 and 1933 mass flights to Brazil and Chicago, including “very rare errors of the fantastic ‘triptichi’ that were issued for that [Century of Progress Exposition] flight.”

At the end of his fourth segment, Harris concluded that “it has been possible, in this review, to mention only those few items in the vast collection which are of particular interest by reason of their scarcity or their special interest to [the author].” And that was a summary of just one section of the FitzGerald collection.

More of Sybil FitzGerald’s airmail jewels

Mackay’s article whets the airmail collector’s appetite for more. He wrote, “The collection thus originated in France and the French section is particularly strong, including an album devoted entirely to ‘Papillons de Metz’ and pigeongrams and balloon material from the Siege of Paris.”

These were airmail innovations of the Franco-Prussian War that made postal communication possible between residents of Paris and other French cities in 1870 and 1871 while they were surrounded by Prussian forces and thus cut off from surface transport to and from the outside world. Letters were flown out of Paris aboard manned hot air balloons (ballons montes in French) that flew over the Prussian lines.

Getting mail into Paris from the outside was more difficult, because balloons could not be effectively piloted. They drifted in whatever direction the wind carried them.

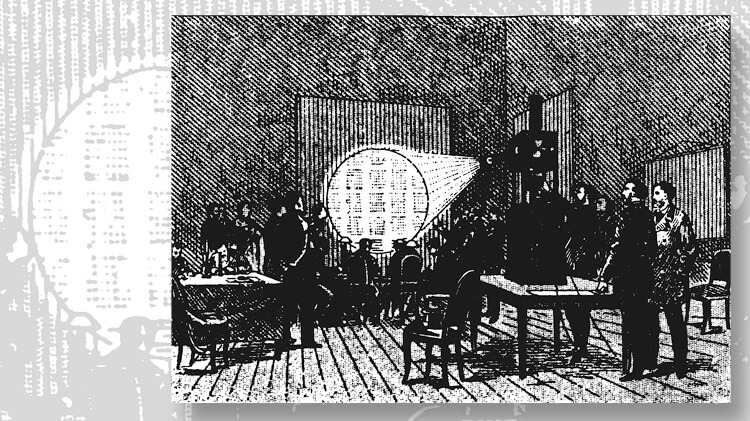

The solution was to use homing pigeons to carry messages back into the city, which required the use of high-resolution microfilm, a remarkable technological feat of that era.

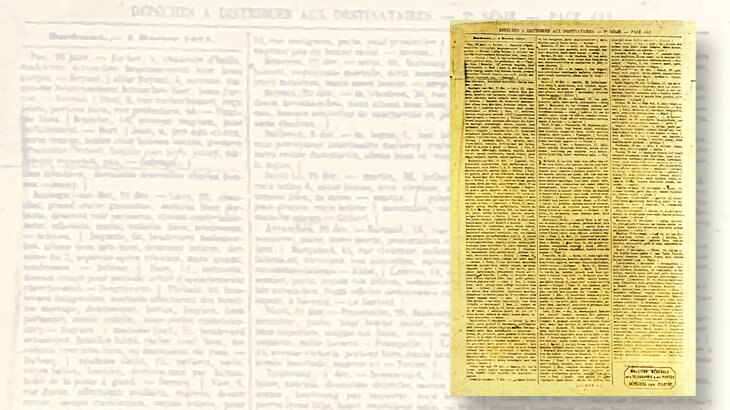

Both official and private communications were sent by pigeongram, but private messages were limited to 20 words. Letters and notices were set in type and printed by letterpress on large sheets, which were photographed onto microfilm. One 15-centimeter square piece of film copied 12 to 16 pages of those prints, which contained about 3,000 messages. Upon arrival the prints were enlarged, copied onto paper, and delivered as letters.

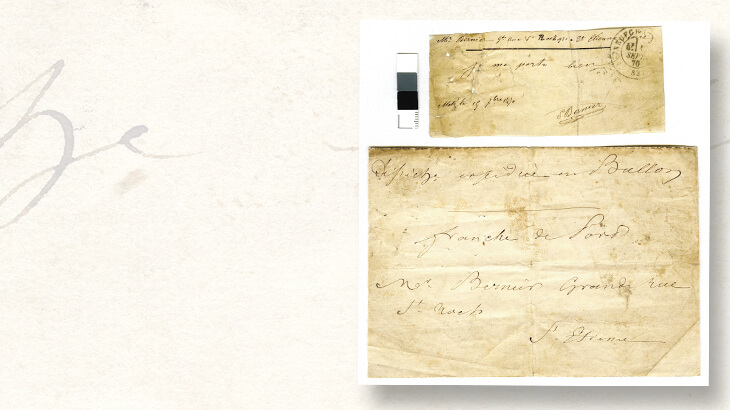

Letters from the siege of Metz are much scarcer than ones from Paris. Mackay commented:

It would be difficult to enumerate all the gems in this section, but pride of place must be given to the “Papillon de Metz” complete in its envelope, perhaps the only one in existence in this condition. It was flown out of beleaguered Metz by balloon on September 15th 1870 and backstamped at Neuchateau two days later before onward transit to St. Etienne.

That item is illustrated with this column. Unlike the Paris flights, the Metz balloons were not manned. They were small orbs that enclosed thousands of letters written on small scraps of thin paper called papillons, filled with gas, and launched from the top of a shed, borne by breezes out of Metz and past the Prussians (although several were captured), with an attached notice that read, “The person finding this packet, who will take it to the nearest post-office, will receive in exchange a reward of 100 francs.” The post office forwarded the recovered papillons to the addressees.

Additional contents of the FitzGerald collection continue as a roster of notable airmails of the world. Mackay wrote that the Newfoundland section of the collection is the most valuable. India is represented by covers, cards, photographs, and press clippings of the 1911 Allahabad pioneer flight. Colombia is represented by the June 1919 overprinted provisional stamp for an experimental flight from Barranquilla to Puerto Colombia, and by large colorful 1920 stamps and flown covers of the Compania Colombiana de Navigacion Aerea.

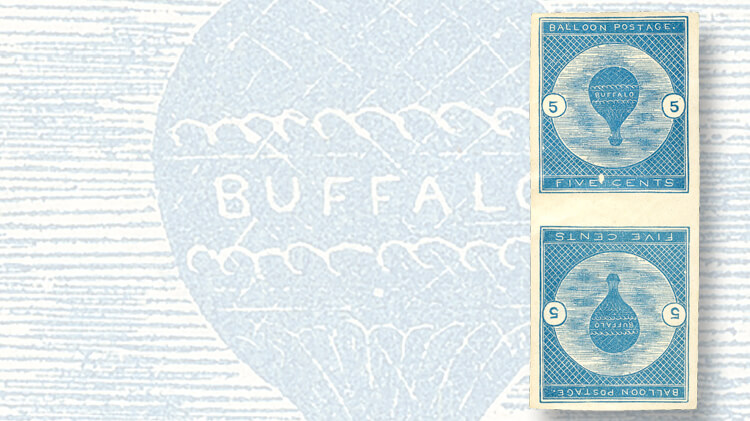

One could go on for many more pages describing splendid material in the FitzGerald collection, but I shall conclude with one of my personal favorites, a tete-beche pair of the United States semi-official Buffalo Balloon stamp, the earliest airmail adhesive stamp, Scott CL1. The stamps were privately issued by John B. Lillard of Tennessee and used on letters flown aboard Samuel Archer King’s gas-filled balloon Buffalo on June 18, 1877, from Nashville to Gallatin. Only 300 were printed.

A permanent home for FitzGerald’s precious airmails

The British public became aware of the lady’s generosity on Aug. 11, 1951, when The Times announced, “Gift to British Museum; Fitzgerald Collection of Airmail Stamps.” Under terms of the British Library Act of 1972, the museum’s library departments, including the philatelic collections, were transferred to the British Library in 1973. The library moved into its present building at St. Pancras in 1997.

Starting from scratch today, it would be almost impossible to duplicate Sybil FitzGerald’s achievement, but her donation has made possible the enjoyment and study of her world airmail trove for the past 60 years and into the distant future — philatelic philanthropy at its best. She also contributed generously to the London international stamp exhibition of 1960, and to the British Museum’s purchases of rare books.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to David Beech and Nicola Davies of the Royal Philatelic Society London for research assistance; to Paul Skinner, curator of philatelic collections at the British Library, for the philatelic images reproduced here; to Gary W. Loew for tech support; and to Ellen Peachey for genealogical guidance. The photograph of Sybil Wyndham is in my collection.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers