US Stamps

Expertizing something that doesn’t exist

By John M. Hotchner

It isn’t often I get a belly laugh out of a letter from a reader, let alone one on the subject of expertizing. But John Burns from Stevensville, Mich., did it with the following missive:

“Many decades ago I collected Germany and specialized in the inflation issues. I don’t remember the Michel number or the post office which issued this particular sheet. I was a member of the Germany Philatelic Society and had stamps expertized through them.

“They would send my grouping to a German expertizer, by name of Schulze. He would stamp the back of each stamp, whether mint or used, with his personalized stamp.

“Anyway … this one issue had three shades according to Michel. The ‘c’ shade was rather rare and identifiable only by the marginal marking, which would indicate which post office had issued any one particular stamp. I had a mint plate block, upper left, with full margins. It came back marked ‘c’ and with Schulze’s mark.

“A few years later, Michel removed this particular shade from the catalog with the explanation that the shade had never really been a shade. So I had an expertized block of something that didn’t officially exist.

“I am left with the conclusion that shades and colors, like beauty, exist only in the eye(s) of the beholder.”

Connect with Linn's Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

This problem is not unique to Germany. An example from the United States is the early (1909) Washington-Franklin stamps on so-called China clay paper.

There are a good many certificates out there saying that the China clay paper version is genuine. However, some years ago, technical studies determined that such stamps were simply a variant of the bluish papers (that are actually grayish-blue — made from 35-percent rag stock instead of all wood pulp) listed in the Scott catalog (Scott 357-366), and so, Scott removed the China clay paper listings.

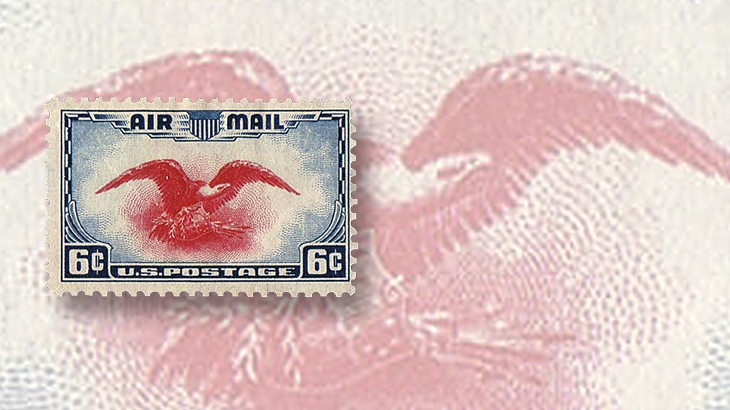

Another possible candidate for delisting is Scott C23c, the 1938 6¢ Eagle Holding Shield airmail stamp with an ultramarine frame. Scott describes the normal variety of this stamp, C23, as having a blue frame. As for the ultramarine shade, partisans swear it exists. Others swear just as vehemently that it does not, saying that it is some sort of changeling. I have never seen one, so I have no opinion, but it is not a settled matter.

The editors of Scott, and other catalogs, generally have to see a variety in person and have a confirming expertizing certificate before they will list. So I don’t doubt that one or both of those requirements were met before Scott C23c was listed. But I also have no doubt that, as with the China clay paper, new information can result in changes.

‘CLEAN’

A Linn’s reader who wishes to remain anonymous has asked what the description “clean” means, and how it relates to expertizing?

Generally, this description is applied to covers, and means that the cover in question is in prime shape for the type of cover it is. That may vary. We don’t expect a Civil War prisoner of war cover to be in perfect shape, but it could be considered clean if free of major flaws and would be a desirable addition for all but the most fastidious of collectors.

In the expertizing world, “clean” is not a description that is seen on certificates; it is not specific enough. If there are flaws, they need to be described in detail on the certificate.

However, it is a term that expertizers use among themselves, most often in combination with the word “too”, as in “too clean.” This refers not to condition or desirability so much as to the physical appearance and genuineness of the cover — and it is not a compliment.

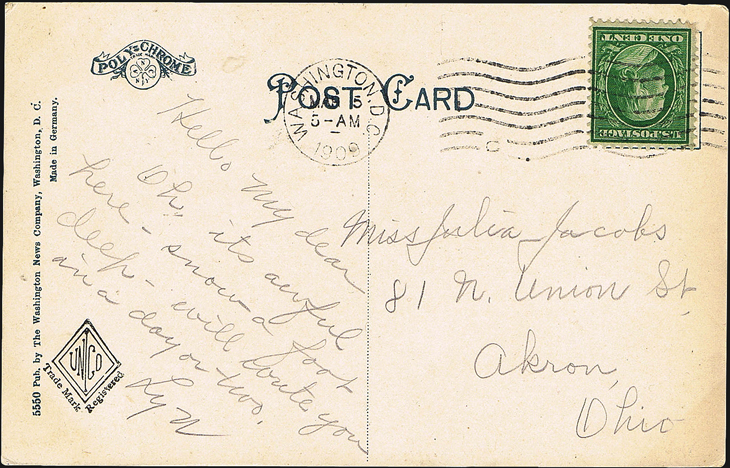

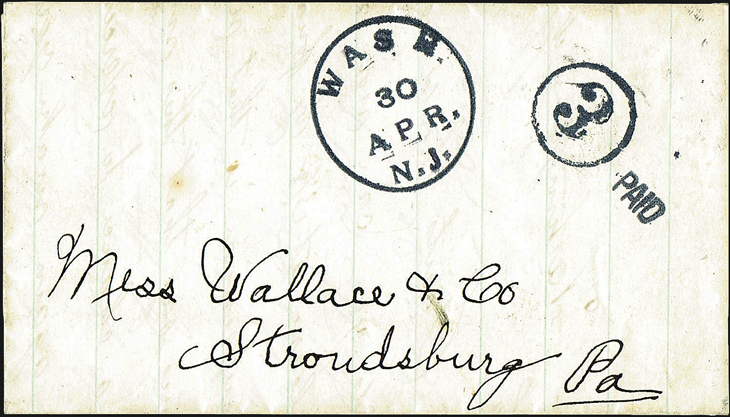

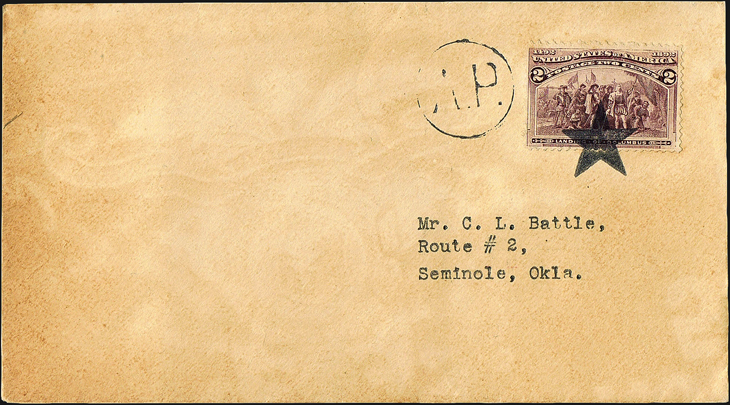

Two examples shown with this column are both too clean, and both are fakes. They are too perfect to the eye; the cancellations are too sharp; and the paper is of a quality that is uncharacteristic of the purported period of use.

In the case of the cover with the 1893 2¢ Columbian stamp (Scott 232), I am no expert on typewriters, but the typing is so clear as to be made by a machine more commonly seen well into the 20th century.

The 1862 stampless cover was done using ink that is darker and richer than handwriting or cancellations of the period.

I’ll add another item that is illustrative. While postmasters often tried to get a fancy or geometric cancellation smack on 19th-century stamps, the checkerboard cancellation on the Franklin stamp shown nearby is too perfect, and the ink is suspect as well.

When I first saw this item, it was offered as an 1861 30¢ orange (Scott 71). The color is right, but the stamp is wrong. Because the “cancellation” pretty much obliterates the stamp, a quick look could mislead the viewer.

A closer look at the bottom of the stamp reveals that it is an 1875 1¢ Franklin Official with “Specimen” overprint (Scott O1S). It is not only the wrong color, because the 1¢ Franklin postage stamp is blue, but the word “specimen” has been blocked out as part of the cancellation, too.

The lesson is that we need to be skeptical of the too perfect. Such an item can be genuine, but often it is not.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers