US Stamps

How many experts does it take?: U.S. Stamp Notes

By John M. Hotchner

How many experts does it take to reach a valid conclusion about any given patient?

One expertizing service trumpets as a positive that it requires that three experts examine every patient (a stamp or cover submitted for authentication). In my view, this is an appropriate standard for many, maybe even most, patients, but excessive for others.

If a service wishes to expend resources regardless of cost, that is its privilege. But many submissions for expertizing are not genuine on their face, and it takes only one qualified expert to make that judgment.

Connect with Linn's Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

For the rest, multiple experts looking at the patient is a good thing, and I don’t know of any expertizing service that does not devote the needed resources to assure that the opinions rendered are at a high level of excellence.

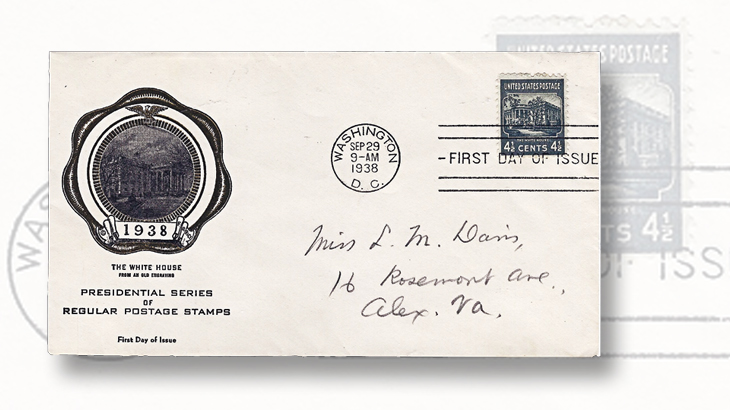

Shown nearby is an example of a bad patient that can be readily and conclusively identified by a single expert. This first-day cover is a Rice cachet produced for the 4½¢ Presidential series stamp issued July 11, 1938 (Scott 809).

The cachet is genuine. The stamp is genuine. The cancellation is genuine. But the cancel date is Sept. 29, 1938, the issue date for the $2 Prexie. This little gem was discovered by 4½¢ stamp scholar Stanley Christmas from Texas.

My guess is that the person who sent this in for cancellation had the uncanceled cover and missed the date by which it had to be sent for servicing. So the next best thing would be to get a later genuine first-day cancellation. Who would ever notice the difference in date?

The next question is: Why would the post office cancel a cover with the wrong stamp? Well, given that a clerk is feeding covers into the machine rapidly, it probably was not noticed. And, if the clerk did notice, the stamp on the cover more than paid the correct rate. So, the easy thing to do would be to cancel it and send it on its way.

I can’t imagine that this is the only time this sort of thing has happened. Over the years I have seen a good many covers that went through the machine with no stamp at all!

But for our purposes here, the fact is that this cover is not a genuine 4½¢ stamp FDC, and it does not take three experts to make that determination unless the first two didn’t notice the wrong date, which is highly improbable.

Let’s look at another example, one that is more commonly seen. In the nearby illustration of two 1991 29¢ Wood Duck stamps (Scott 2484), the example on the left is normal, and the example on the right is supposedly missing the brown color in the duck’s body.

To a competent expert, this screams “fake.” There is no listing in Scott for such an error. That, of course, is not fatal. New discoveries are possible.

However, there are four other factors that make this patient problematic.

First, under 30-power magnification, it can be seen that no colors are completely omitted.

Second, other colors have been affected by whatever bleached out the red and yellow that combine to make up the brown. Note especially the normal red duck bill and the red eye. They are washed out in the fake.

Not so easily seen is that the green in the head is bright on the normal, and quite flat on the fake. Further, the background white paper on the fake is much whiter than on the genuine, and looking at the stamp under long-wave ultraviolet light reveals that the tagging has been altered by whatever method was used to try to bleach out the red and yellow.

The bottom line is that it is not an error, nor is it just a light print of the yellow and red. It is a stamp that has been altered to make it appear that it is an error. One expert who knows what he or she is dealing with can make that determination. And the moment this determination is made, no additional experts are needed. In such cases, the decision of an expertizing service not to employ additional experts has nothing whatsoever to do with maximizing profits.

Much of each packet of material I get to expertize is easily determined as fake; on average as much as a quarter. The remainder will profit from analysis by more than one expert, but subjecting the easily determined fake to additional scrutiny delays the opinion getting back to the submitter and wastes resources.

New resource for Confederate States of America collectors

Self-education is the best way to avoid paying for expertizing. Often, the cost of the book or pamphlet is more than made up for by being able to be a smarter purchaser and by being able to determine what really does or does not need expertizing.

Confederate States collectors have an excellent new resource: Confederate States of America Philatelic Fakes, Forgeries, and Fantasies of the 19th and 20th Centuries by Peter W.W. Powell and John L. Kimbrough.

This 430-page hardcover book is a comprehensive treatment encompassing both stamps and covers and including a multitude of color illustrations.

The stamp section leads off with the history of the ubiquitous facsimiles often seen in United States collections, and is then organized by the known fakes and counterfeits of general-issue stamps, with additional chapters on perforated and rouletted stamps.

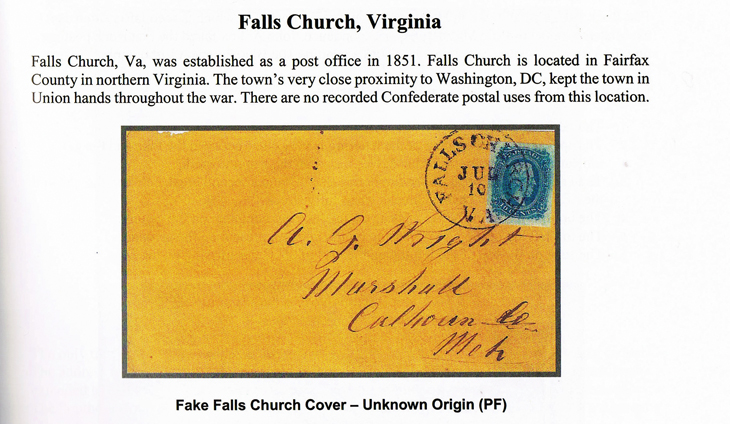

Covers and cancels are then dealt with in alphabetical order according to city and town name. As an example, I turned to Falls Church, Va., where I live, and found the cover shown here. The description printed in the illustration continues with this additional detail:

“The cover illustrated above has an Archer & Daly Type I stamp tied by a Falls Church, Va. postmark. The cover looks very good and could easily pass as a genuine Confederate cover at first glance. However, it is an impossible use as there can be no Confederate mail from that area in 1863 or 1864. Furthermore, the address is to a town in Michigan. The American Stampless Cover Catalog lists a 32mm Falls Church postmark used pre-war but does not illustrate it. This could either be a very cleverly altered pre-war cover or a total fabrication.”

The book can be ordered from Peter W.W. Powell, 5502 Cary Street Road, Richmond, VA 23226. The cost is $95, postpaid within the United States.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers