US Stamps

How is fraudulent matter to be handled in domestic mails?: Modern U.S. Mail

By Tony Wawrukiewicz

The items pictured in this column were purchased on the online commerce website eBay this past March. I feel blessed to have found them, because they explain the very important concept of “fraudulent matter” that is first found in the 1873 Postal Laws and Regulations (PL&R).

This category is now “false representation matter” in today’s domestic service manuals. Thus, although this column deals with fraudulent mail, it also is discussing what is now called false representation mail.

By postal standards, fraudulent matter includes any scheme for obtaining money or property of any kind through the mails by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations or promises.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

The next paragraphs are concerned with how fraudulent mail matter can be legally discerned and acted upon.

With a few exceptions, as will be noted, these rules of action essentially were in place from the 1873 PL&R through the 1970 Postal Manual. These rules of action changed because by 1967 the use of the term “fraudulent” was being phased out, and slowly replaced by the term “false representation.” The same type of matter was involved, just titled differently.

No person other than an employee of the Dead Letter Office or Dead Letter Branch, duly authorized thereto, or other person upon a search warrant authorized by law, was authorized to open any letter not addressed to himself.

However, the postmaster general could discern, upon evidence satisfactory to him (such as through advertisements, legal Dead Letter Office/Dead Letter Branch mail-opening, or other legal sources), that mail was fraudulent, and act upon it. In this manner, the postmaster general could ascertain that matter was fraudulent and inform all postmasters.

Thereafter, a postmaster at any post office, having been notified by the postmaster general of any scheme for obtaining money or property of any kind through the mails by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations or promises, and encountering any such mail matter, was to return all of it (only if it was registered mail, according to the 1873 PL&R, but all such mail, registered or not, as of the 1932 PL&R) to the postmaster at the office at which it was originally mailed.

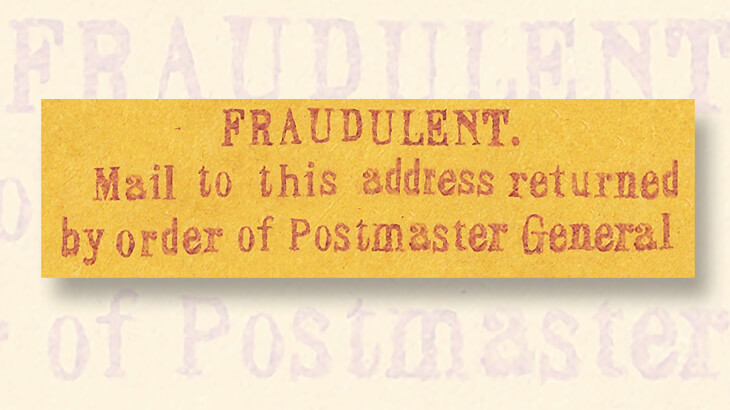

The word “Fraudulent” was to be plainly written or stamped upon the outside thereof, and all such mail matter so returned to such postmasters was to be returned by them to the writers thereof, under such regulations that the postmaster general might prescribe.

Note that only the word “Fraudulent” was to be placed on the fraudulent matter from 1873 until 1893, and “FRAUDULENT. Mail to this address returned by order of Postmaster General” from about 1900 onward.

Now, let us discuss essential matters from 1873 to 1947, using a 1947 example that conforms to the laws and regulations of the time (and since 1873).

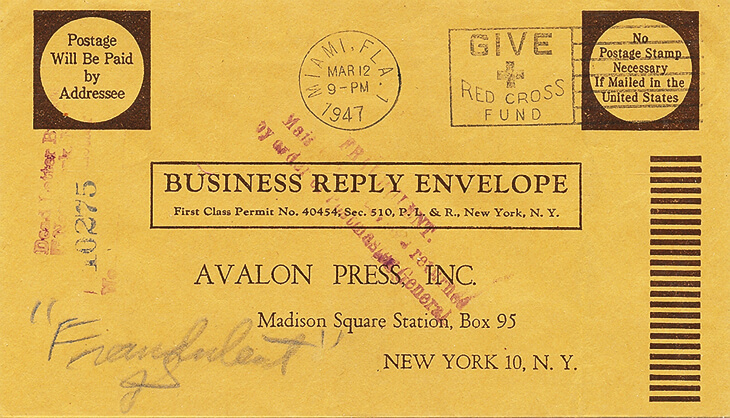

The business-reply mail envelope without a return address in the first image beautifully illustrates a return of fraudulent matter to the writer.

In this case, the writer mailed a business-reply envelope back to a fraudulent enterprise. This was recognized by the postmaster of the delivery office of this fraudulent business, who wrote “Fraudulent” on it, but because the letter had no return address, the postmaster could not return it directly to the writer.

Thus, it was correctly sent first to a Dead Letter Branch in New York City where it was opened, the writer was determined, the envelope was rubberstamped “FRAUDULENT. Mail to this address returned by order of Postmaster General,” and the business-reply envelope was then enclosed in an outer envelope and returned to the writer as required.

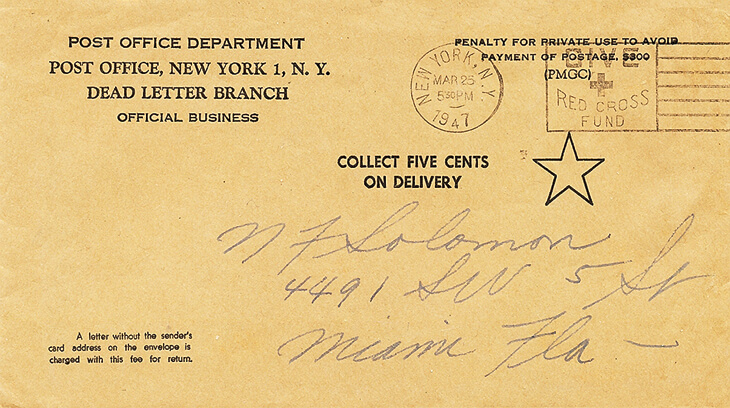

The addressee on the Dead Letter Branch return envelope, which is also pictured here, lived in Miami, Fla., where the business-reply mail letter had originally been postmarked. The return envelope incorrectly has no 5¢ postage-due stamp on it (to indicate collection of the 5¢ Dead Letter Branch fee).

This return envelope is the third one I have seen with a simple five-pointed geometric star on it. I am guessing that it is equivalent to the six-pointed Star of David marking shown in my column in the Nov. 9, 2015, Linn’s, that being a symbol indicating that the minor division of the Dead Letter Office or Dead Letter Branch handled the return of a dead letter that contained an enclosure of importance to the sender, but not of great monetary value, such as postage stamps, photographs, papers and so on.

Incidentally, although according to the official documents only registered fraudulent matter was to be returned from 1873 until 1932, I have never seen a registered fraudulent item returned.

Also, although in various official documents fraudulent matter was cited as being unmailable, in reality, as this illustration confirms, the postmaster at delivery offices most commonly noted a fraudulent item that he or she had correctly returned to the writer.

That is, the item was returned as undeliverable, not as unmailable.

Tony Wawrukiewicz and Henry Beecher are the co-authors of two useful books on U.S. domestic and international postage rates since 1872. The third edition of the domestic book is now available from the American Philatelic Society, while the international book may be ordered online.

More on Modern U.S. Mail:

More about understanding pressure-sensitive package labels

What postal rule forbade remailing in an undeliverable envelope?

No postal rule, but reality of remailing unclaimed, undeliverable mail

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers