US Stamps

Pre-expertizing? An idea whose time has not come

U.S. Stamp Notes — By John M. Hotchner

Two readers of this column independently came up with a similar suggestion. Combining their observations, they say: “I have 400-odd specimens for which I would like certificates (and/or numerical grades), but that would cost several thousand dollars. So, as a practical matter I have the dilemma of choosing which material to get expertized. Is there a pre-expertizing service available?”

They continue by describing how such a service would operate, suggesting that it could be an individual or a commercial service that would, for about $5 per item or a lot price for a larger quantity, render a nonbinding opinion, selecting those items most likely to get a good certificate.

They add that the owner would have to sign a statement agreeing that this is only an opinion and not a guarantee of a favorable finding.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

I have no doubt that there are people who would be willing to do this — and some who actually do — but not as an established for-profit service.

I also am certain that individual collectors who are competent in their specific areas will do this as a favor for friends or stamp club buddies, though not in quantities of 400.

But the answer to the question “Is there such a service?” is no, not to my knowledge.

There are some practical problems that probably account for why such pre-expertizing is done informally and not as a commercial service.

The rules change when something done as a free opinion becomes a for-profit enterprise. Such an entity would have presumed legal accountability for its opinions. Does signing a statement negate that? I’m thinking the legal fees to sort all this out could rapidly overwhelm any possible profits.

And what would happen when an unhappy submitter then spends the money to get a certificate, and it comes back “not genuine?” Or maybe even worse, the submitter eventually finds out that something he did not submit for a certificate is actually genuine, but the pre-expertizing service missed it?

The submitters are not going to be happy, and regardless of the signed statement, the telling and retelling of the story is going to have an effect on the reputation and quantity of work the service would receive.

Then there is the ethical dilemma those working in a pre-expertizing service would have if they are also experts who work with the established expertizing houses. Is it proper to be paid for, in fact, generating work for your expertizing service, or for reducing the workload of your service?

There also is the likelihood that some submitters would choose to rely upon the pre-expertizing service as if it were a real expertizing service.

I can hear it now, “Well, so and so [a well-known person in the hobby] thinks it is genuine, so I’m going to offer it as such.” However, the opinion is not backed by a reputable expertizing house, and there is no certificate. How does that translate into dollars for the seller and the buyer? This quickly becomes a quagmire.

There also are the staffing and competence angles to be considered. There is no expert who knows everything about everything, and assembling the stable of experts to populate such a service would be daunting.

Experts who work for recognized expertizing houses receive negligible compensation; a pre-expertizing service would have to pay even less. Could it even attract the most competent experts?

And suppose an expert receives an item, and spends half an hour looking at it and researching it in literature, and still can’t in good conscience reach a conclusion. Does the fee get returned?

Taken together, these issues constitute a powerful set of reasons why such a pre-expertzing service has not been established.

A lesson in humility

As I have already mentioned in this column no expert, collector or dealer knows everything about everything. Even though I have been involved in the stamp hobby since the age of five, I am regularly reminded of what I don’t know. The current case relates to an 1857 3¢ cover (Scott 26).

Always on the lookout for odd philatelic items, I bought the cover because of the olive green cancel. Any green cancel in that era is a nice find and the price was right, so even though I did not have a Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers handy, I made the purchase. The dealer knew what he had because he wrote “green cancel” on the cover holder.

When I got the cover home, I looked it up in the Scott U.S. Specialized catalog and was surprised to find that there is no listing for an olive green cancel on Scott 26. I consulted my friend William T. Crowe, who is an expert in early United States and one of the few people in this country who does expertizing and issues his own certificates.

Crowe’s response taught me something new: “It is a genuine stamp, tied by an oily black cancellation, that has degraded with the passage of time giving the appearance of an olive green cancellation, on a cover addressed to Sag Harbor, L.I. (New York).”

So, regardless of what it looks like, it does not qualify for a Scott listing. Instead it goes into my “odd stuff” collection. I had no idea that black ink could degrade in this fashion.

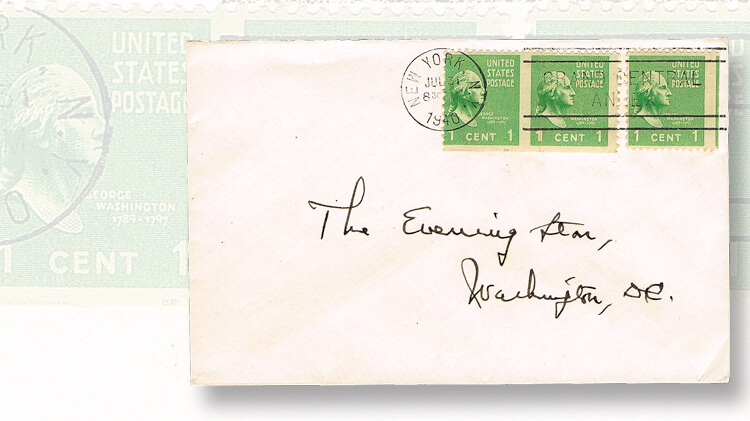

My second example of something that is not what it appears to be is a 3¢-rate cover franked with three 1¢ George Washington stamps from the Prexie (Presidential) definitive series of 1938. The cover was sent from New York City to Washington, D.C., in 1940.

The two stamps at left on the cover look like an imperforate-between pair with no perforations at the bottom.

Indeed, such an error is listed the Scott U.S. Specialized catalog as No. 804c: “Horiz. Pair, imperf between (from booklet pane).”

But on close examination, what we have here is two stamps from the bottom of a miscut booklet pane of six. The two stamps on the cover were stamps 5 and 6 from the booklet pane, but they have been pasted on the cover in reverse order (6 and then 5), leaving perforations at left and right and the imperf margin of the miscut pane in the center.

The preparer of the cover might have done this on purpose or by accident, but left a hint by using a wide cut, right-hand stamp from the miscut pane (either stamp 2 or 4 from the same pane) on the cover. We can see how the two left-hand stamps were put together with a margin between that appears to be imperforate.

However, if you look carefully at the “1” in the lower left of the second stamp in the pair, you can see where the two stamps were joined.

I found this cover in an accumulation, and it cost me less than $1. It was not represented as an error, but you can see how it might easily be. The actual error is so scarce that Scott places a dash in the used column to indicate that there is insufficient information to serve as basis for assigning a value.

My bet is that the example that served as the basis for the Scott listing is unique.

The point I am trying to make with these two examples is that it is too easy to see what we want to see when looking at what might be a desirable item.

Expertizing provides the needed disinterested knowledge and perspective to properly identify questionable items.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers