US Stamps

Double prints simulated by tagging ghosts

U.S. Stamp Notes — By John M. Hotchner

A recent submission to one of the expertizing services I work with brought up a common misunderstanding regarding modern United States stamps.

Take a look at the 1971 21¢ “USA” and Jet airmail stamp shown here (Scott C81). What do you see? Here’s a hint: Look at the top of the red letters.

Shown in the same illustration is a strip of three 17¢ Statue of Liberty airmail stamps (Scott C80), also a 1971 issue, that exhibits the same effect. On this strip of three, both the red and blue text are affected, with progressively more intensity starting from the top stamp and going down.

These appear to be doubled colors, and they are. The question for an expertizer is “Why is there a doubling?” Some who encounter these varieties will jump to the conclusion that they are a double print — or as Scott catalog editors call it a “double impression” — defined as two distinct but not completely congruent strikes of the plate on the paper in two passes through the press.

When that happens we have a catalog-listable error. It is a relatively rare event.

Most of what we see as doubled designs or design elements on U.S. stamps do not qualify as this type of error. They are either tagging ghosts, which I will examine in more depth in this column, or stuttering, where the plate and paper meet multiple times in one application of ink. The latter are mostly seen on the offset issues of the Washington-Franklin series.

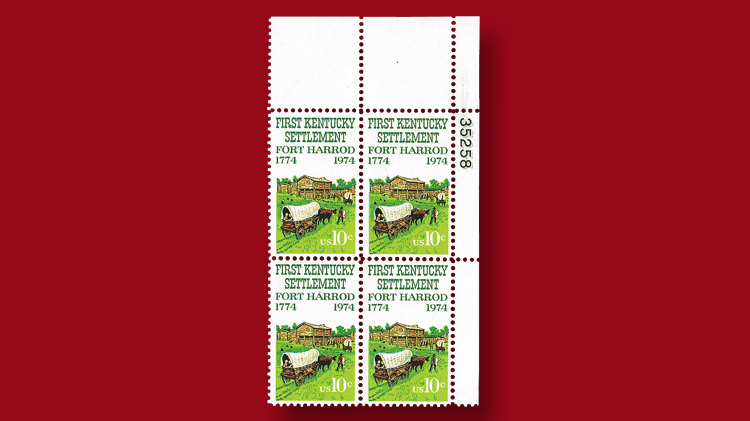

The items illustrated with this column are all tagging ghosts. We usually see these associated with plate numbers, such as with the block of four of the 1974 10¢ Kentucky Settlement 200th Anniversary commemorative (Scott 2542) shown here.

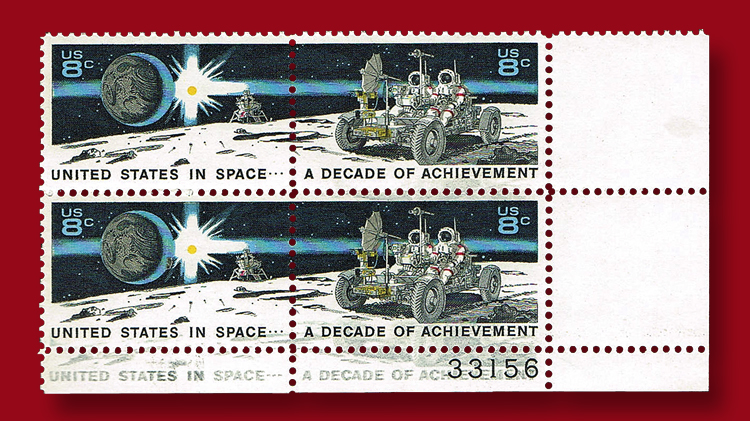

However, there are a few instances where tagging ghosts have been found doubling one or more design elements. Two additional examples are illustrated here: a 21¢ airmail block with the doubling on a diagonal, and the 1971 8¢ Space Achievement Decade plate block (Scott 1434-1435) with the doubling below the bottom stamps.

So, how did this happen and why? The answer begins in 1963 when the U.S. Post Office Department began experimenting with the application of phosphorescent tagging compounds to U.S. stamps.

The initial purpose of tagging was to electronically separate domestic airmail from regular mail. Eventually, that was no longer necessary when the separate domestic airmail category was eliminated in October 1975 in favor of transmission of all first-class mail by the fastest available means.

But the experiment had been successful and provided the basis for automating a labor-intensive task: the identification for the canceling machine of the upper right front corner of each envelope where the stamp was that needed to be canceled.

How? By electronically finding on each envelope the corner bearing a tagged stamp, and arranging or “facing” the envelope so that corner would go through the canceling device.

The equipment developed for that purpose, called a “facer-canceler,” took a jumble of letters fed in at one end and produced a neat stack of properly faced and canceled envelopes at the other.

To do this required an identifiable “signature” on stamps, in other words, something that the facer portion of the machine could recognize and act upon.

A phosphorescent and mostly colorless ink was applied by a separate sheet-fed offset press on top of the just-completed stamp designs. It’s at this point that the ghosting took place.

If the printed stamps were not yet completely dry — intaglio inks used to print plate numbers and some design elements at this time were especially slow to dry — the tagging cylinder would pick up part of the intaglio or offset ink on sheets passing through.

It would then deposit the borrowed impression with the intended tagging on the next sheet, and sometimes on several sheets.

If the sheets were in proper register as they went through the offset tagging press, the deposit of wet ink from preceding sheets is not normally evident anywhere but in the plate number, as seen here on the 10¢ Kentucky Settlement plate block.

Often, only the last one or two numbers of the plate number are different because sequential plate numbers were often paired on the press.

However, if the sheets were not in proper position as they went through the tagging press, the colors deposited with tagging would appear to double the design elements. The few of these that exist are nearly always exactly horizontal or vertical with respect to the direct print, but the diagonal impression on the 21¢ airmail is one of the most spectacular flubs you will ever see.

There is yet one more cause of doubling, and it is fairly common. Called a “double transfer,” it normally affects only a specific portion of the design of intaglio-printed stamps. It is caused by the incomplete burnishing out of a poorly done entry on a printing plate. When the design is reentered, both it and the remaining design from the first try will be evident.

Double transfers are so numerous in early U.S. philately, that only major examples are listed in the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers.

Current Literature

The March issue of the United States Specialist, the monthly journal of the United States Stamp Society, includes two short, illustrated articles of interest to students of fakes and forgeries and expertizing, and to collectors of the Washington-Franklin series of 1908-22.

The first is “Lot Describer’s ‘Excellent’ Coils Should Caution Those Daring to Collect Washington-Franklins” by Kevin G. Lowther. The second is “Even Cheap Stamps Get Faked Too” by Gerald Nylander.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

The United States Specialist is always an exciting read, covering many aspects of U.S. stamps and postal history, with an emphasis on 20th-century material, and U.S. collectors would be doing themselves a favor by joining the society. Information about the organization and membership can be obtained from its website.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 2 PMGratitude for Denise McCarty’s 43-year career with Linn’s

-

US Stamps

Oct 9, 2024, 12 PMWorld’s first butterfly topical stamp in strong demand

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 3 PMRoyal Mail’s Oct. 1 definitive meets new international standard rate

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 12 PMPostcrossing meetup Oct. 9 at U.N. headquarters