US Stamps

The challenges of sending POW mail during the Civil War

By Labron Harris

Of all the ramifications of war the United States and the Confederate States faced, the problem of dealing with prisoners of war was the one they were the least prepared for. With the secession of the Southern states, conflict was inevitable.

The first Civil War encounter that ended with prisoners held was in St. Louis, where at Camp Jackson on May 10, 1861, 669 members of the Confederate Missouri State Militia were captured.

Upon signing an oath not to bear arms against the United States, they were paroled. One man, Capt. Emmett MacDonald, refused to sign the oath and became the first prisoner of war.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

One prisoner did not create a problem concerning where and how to incarcerate him. But soon it became a major issue.

No provisions had been made to house large numbers of prisoners by either side. No one expected the war to last very long, a few months at the most.

This all changed on July 21, 1861, at the Battle of Bull Run near Manassas, Va. The Confederates ended up with more than 1,000 prisoners with no place to house them.

They settled on an old tobacco factory in Richmond, which became the first Confederate prison, known as Ligon’s Tobacco Warehouse.

Although the battle was a Confederate victory, the Union took prisoners as well, and the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., became the first building to house Confederate prisoners.

When the Battle of Ball’s Bluff occurred in October 1861, the shortage of POW housing became acute. With the South taking a large number of prisoners, Ligon’s Prison proved inadequate to house them.

The Union had already started the construction of a prison named Johnson’s Island near Sandusky, Ohio, and planned to hold the prisoners captured by them there.

The Confederates quickly opened prisons at Salisbury, N.C., Tuscaloosa, Ala., and Charleston, S.C.

The number of prisoners was quickly becoming a huge logistical problem. In December 1861, a measure to enable the exchange of prisoners was passed to lessen the burden of inadequate housing.

This bill, called the Dix-Hill cartel, was enacted July 22, 1862, and the regular exchange of prisoners began.

The exchange, which slowly was being abandoned, was ended completely on April 14, 1864, by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who said it was “cheaper to feed them as prisoners than fight them as soldiers.”

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were taken prisoner. Correspondence is known from Union prisoners confined in more than 50 Confederate prisons and from Confederate prisoners confined in more than 80 Union prisons.

The prisoners on both sides were given a means of both sending and receiving letters. The letters were examined and then forwarded through a designated point of mail exchange by flag of truce, which provided safe passage across the lines to their final destinations.

The primary exchange point was Old Point Comfort, Va., but there were many others.

Restrictions were placed on prisoner’s mail. For most of the war, letters could be only one page long and not contain information helpful to the other side.

For a short period of time only six-line letters were allowed. This system of mail handling was not always able to get the mail through, and a great number of letters were smuggled out by exchanged prisoners.

Lt. David Bartram of the 17th Connecticut Infantry was captured by the Confederates at the Battle of Gettysburg and remained a prisoner until the end of the war. He was first incarcerated at Libby Prison in Richmond, Va., and then in eight other Confederate prisons before his release in 1865.

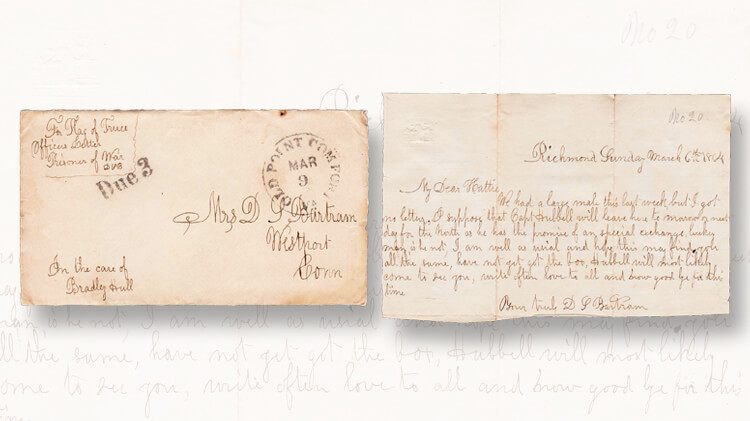

Shown with this column is a cover and a six-line letter (one word carries over to the seventh line) from him in Libby Prison to his wife in Connecticut. It came by flag of truce and entered the U.S. mail at Old Point Comfort, Va., and was marked “ DUE 3,” which required his wife to pay 3¢ postage due.

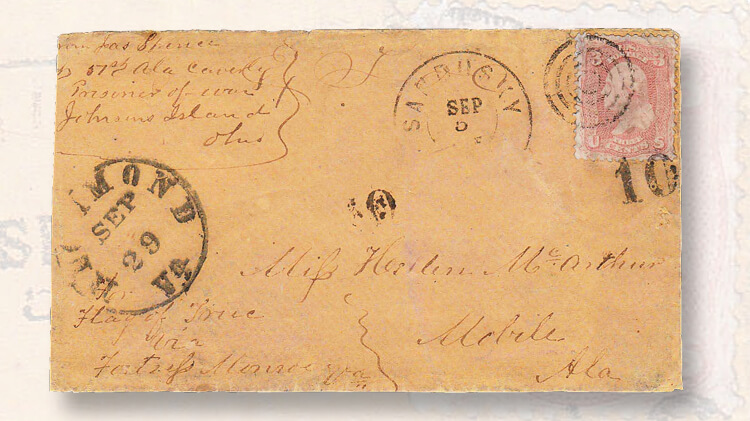

Another cover shown is from James Spence, a Confederate soldier from the 57th Alabama who was imprisoned at Johnson’s Island, the Union prison near Sandusky, Ohio.

This cover was examined by Pvt. Theodore O. Castle (manuscript EX T O C in top center of the cover) and paid to the exchange point, Fortress Monroe at Old Point Comfort. It was then carried by flag of truce to Richmond, Va., where it entered the Confederate postal system, marked “10” (10¢ postage due) and sent to Mobile, Ala.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers