US Stamps

Debunking a philatelic conspiracy theory about the CIA Invert

U.S. Stamp Notes by John M. Hotchner

It is no sin to question established orthodoxy in the stamp hobby, but I was surprised to receive a letter from a collector who theorized that the so-called CIA Invert was not a true invert.

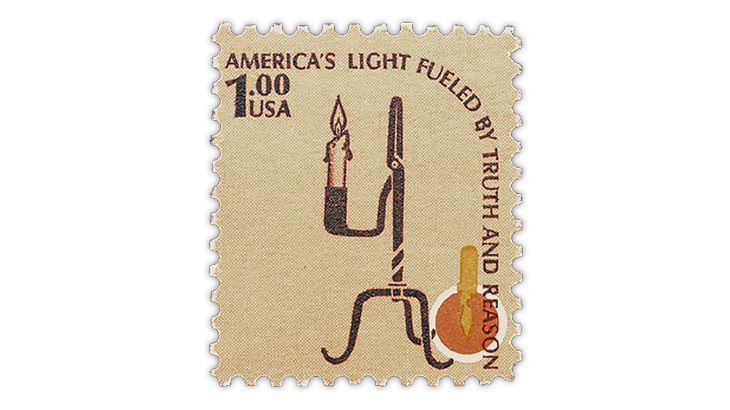

The stamp in question is the United States 1979 $1 Rush Lamp and Candle Holder Americana definitive stamp with the intaglio brown color inverted (Scott 1610c), shown in Figure 1.

The CIA in the error’s nickname refers to the Central Intelligence Agency; an employee of that agency purchased a partial pane of 95 of the stamps for use on CIA mail. The error was discovered in 1985.

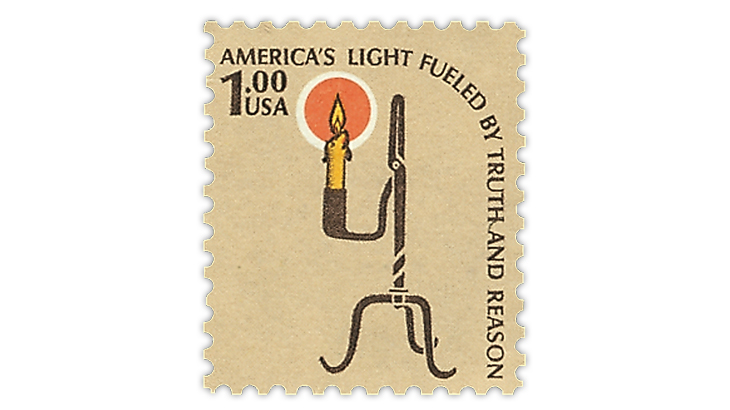

For comparison, a normal example of this $1 Americana stamp (Scott 1610) is pictured in Figure 2. The design shows a yellow candle, with a reddish glow around it, on a tan background, all printed on the Miller offset press. Printed on the I-8 press was the dark brown candle holder and lettering. Both presses were sheet fed.

The letter writer asserts: “Questions have bothered me since discovery of the variety. I do not believe it could be a true invert — that is, run through the presses a second time in an inverted position. If it were a true invert, the flame circle should be in a more central position, not up in a corner. My contention is that the stamp should be classed as a freak — or even printer’s waste.”

As I have discussed in previous U.S. Stamp Notes columns, printer’s waste has two meanings in stamp collecting. In a general sense, any imperfect production is printer’s waste in that it should be caught and destroyed before it leaves the printing plant.

But in the way that the letter writer uses the term, it has a much narrower meaning: imperfect material identified for destruction that is stolen from the printing plant instead of being destroyed. Typically, such material is missing one or more production steps and is often damaged or folded.

The CIA Invert is a completed printing job with the intaglio and offset design elements inverted with respect to one another. The one pane sold at a McLean, Va., post office was undamaged. It is definitely not printer’s waste in the aforementioned narrow definition.

Also, the letter writer did not take into account that the margins of the production sheets of 400 were not equal all around. A single sheet in the midst of a stack being fed into the second process would be an exact match to all the others, but the placement of the inverted element would be displaced from its normal position at the top center by the differences of the margin widths at left and right on the inverted sheet.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing accepted that this was a true invert and launched an inquiry into how it happened to learn what it could do to prevent future errors.

The letter writer thought it suspicious that only one pane of 100 was discovered. What happened to the other three panes?

Actually, we don’t know that the other panes were not discovered. The other three panes could have been discovered during quality control reviews at the BEP, but the inquiry determined that was unlikely.

The fact that one pane was shipped to a post office suggests that others probably were as well. But the United States Postal Service ordered an immediate review of stocks in post offices, looking for more inverts. Even without that, postal clerks might have discovered and turned in anything they identified as defective as operating procedures require.

If other examples of this invert were sold at post offices, they might have been used and suffered the fate of a high percentage of used U.S. stamps. In other words, they were thrown in the trash.

So, there are two possible scenarios of what might have happened to additional panes if in fact they were purchased: The purchaser didn’t appreciate the error for what it was and used the stamp or stamps, or these inverts are in the hands of remarkably patient collectors.

It should be noted that five inverts from the CIA Invert pane had been sold by the post office before the CIA employee bought the remaining 95. Those five stamps were likely used and were consigned to trash cans.

The letter writer also mused on the concept that a “so-called CIA employee” bought the stamps for official use. He suggested that there should be a paper trail if that were the case and also asked: “Why did the CIA office need $1 stamps? Don’t they have free franking?”

The CIA did a thorough internal review of the sale of these stamps by the group of nine CIA employees who bought the inverts at face from the post office and wholesaled them to a stamp dealer.

The review established that the stamps were properly purchased and that they were CIA property. The employees were disciplined because they attempted to convert agency property for personal gain. Four of the employees were terminated.

As to why the CIA would need stamps, consider when was the last time you saw a CIA return address on an envelope. They do exist, but they are few and far between.

Just to take one example, think about the recruitment of new employees, many who will work undercover during their careers. What kind of sense would it make to have recruiting brochures, offers of employment and associated materials arriving in their neighborhoods in envelopes loudly proclaiming to anyone handling them that they are from the CIA?

So, bottom line, the information that has come down to us in the more than 30 years after the discovery of the CIA Invert is rock solid. It is always tempting to spin conspiracy theories, but in this case there is no substance to support one.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers