US Stamps

Determining the rates paid on 1937 50¢ Trans-Pacific covers

U.S. Stamp Notes by John M. Hotchner

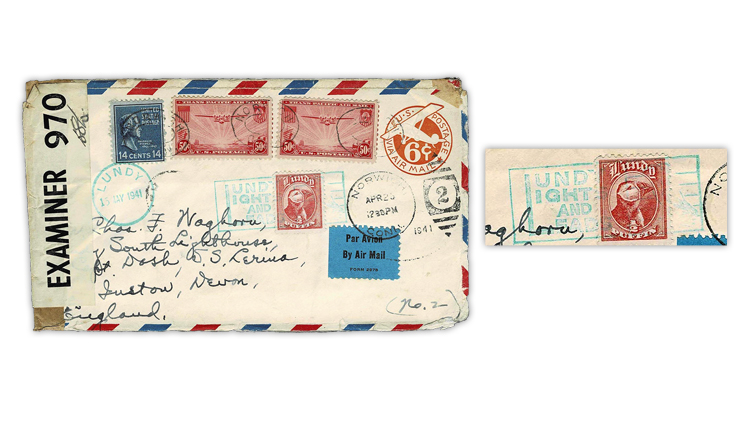

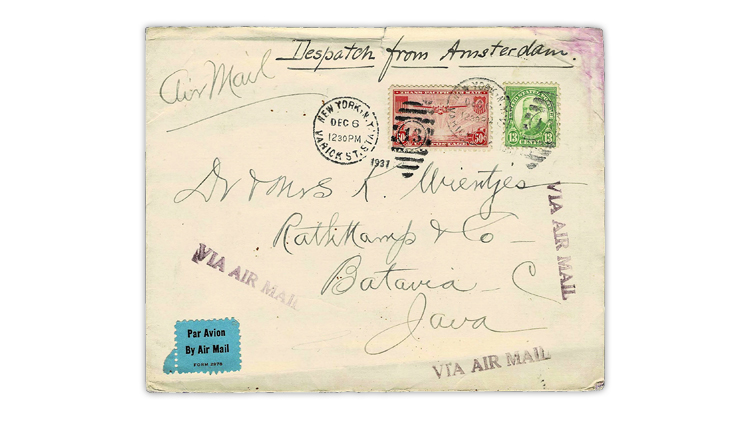

A couple of years ago, something possessed me to start collecting usages of one of my favorite United States stamps, the 1937 50¢ Trans-Pacific airmail stamp (Scott C22). A couple of examples are shown here as Figures 1 and 2.

This inevitably pushed me in the direction of what postal historians call “rating” covers, in other words, calculating what services the total postage on the cover paid for and how the cover traveled to its destination.

It turns out this is not so easy for a 1937 stamp that was used into the 1940s when the events leading up to World War II and the war itself required major changes in the routes that mail traveled.

Much of what had been accessible by clippers flying west from the West Coast of the United States suddenly was closed off due to military operations. These areas could only be reached by way of Africa and the Middle East, if they were accessible at all. So routes changed, and the rates for new routes were not always the same as before.

There also was a certain amount of what might be described as mail by the seat of its pants as events resulted in a certain amount of trial and error before new routes were established.

It has been a challenge for me to understand all of this and apply it to the covers I’ve gathered.

Here I need to give a word of thanks to Ken Lawrence and Tony Wawrukiewicz, both of whom have been Linn’s writers for some years, and to friends Joe Bock, who has studied usages of stamps in the Trans-Pacific set for many years; and Rich Drews, an expert in Lundy Island mail. They have been my “rating” professors.

Let’s take a look at the two covers to give you an idea of the variables involved in rating them.

The cover in Figure 1 was sent from Norwalk, Conn., to England. The U.S. postage totals $1.20: the 6¢ airmail envelope, the 14¢ Franklin Pierce stamp of the 1928 Presidential issue and two examples of the 50¢ Trans-Pacific airmail. But the surprising item on the cover is the canceled ½-puffin Lundy Island stamp.

A small island located off the coast of Devon, England, in the Bristol Channel, Lundy issued its first local post stamps in 1929. The stamps are denominated in puffins, with 1 puffin equaling 1 British penny.

The basic airmail rate to England when this cover was sent in April 1941 was 30¢ per half ounce.

The $1.20 in U.S. postage on the cover paid four times the 30¢ per half-ounce rate for a mailing that would have been heavy, between 1½ and 2 ounces. That seems simple enough so far. But what was the purpose of the Lundy stamp? Was it just window dressing?

Note the addressee and address: Charles F. Waghorn, South Lighthouse, Devon, England, by SS Lerina. Lundy is not included in the address, but that was where the cover was headed.

Keep in mind that a cover going to Lundy Island would not go directly from the United States by air to Lundy, instead it would get to the island by way of the British mainland.

Here Drews came to my rescue. Waghorn, it seems, was the lighthouse keeper on Lundy. He corresponded with collectors worldwide. The ½-puffin stamp was the proper rate of postage for service given between Lundy and the mainland.

On covers leaving Lundy, the local stamp had to be placed on the reverse of the envelope. On incoming mail, the Lundy stamp was placed on the address side.

The plane that had flown to Lundy had gone into war service on Sept. 2, 1939, so then the carriage of mail to and from the island was by boat. Eventually that, too, was taken away for war service, and mail to and from Lundy was suspended for the remainder of the war.

All in all, I think this is a remarkable cover.

The cover in Figure 2 appears deceptively simple. It was sent Dec. 6, 1931, from New York City to Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), franked with the 50¢ Trans-Pacific airmail stamp and a 13¢ Benjamin Harrison definitive.

In December 1937, Java could be accessed from the West Coast of the United States by way of Hong Kong by clipper at the rate of 70¢ per half ounce. But this cover originated in New York, so it made sense to send it by the Atlantic route, by way of the Netherlands. That is why the cover is inscribed “Despatch from Amsterdam.”

Also, the rate for that route was cheaper: 30¢ air to Europe and a surcharge of 29¢ for mail from Amsterdam to the Dutch East Indies for a total of 59¢.

But that is not how the cover traveled. Per Ken Lawrence, the cover traveled on Foreign Air Mail route 18 to Lisbon, Portugal. This was necessitated by France having revoked permission for KLM Royal Dutch Airlines to overfly its territory the previous September. That meant that KLM’s flights to the Dutch East Indies had to depart from somewhere on the other side of France.

So the cover went to Lisbon, Portugal, from whence it had to get to Naples, Italy, possibly by boat, so that it could be included on a KLM flight to Java originating there.

I hope that these two examples give you a feel for the interplay of philately and history, especially how the former cannot be understood without knowledge of the latter.

This has been an object lesson. Just when I thought I knew philately A to, well, at least W, here is another challenge to put me in my place. But it is a grand challenge, and I recommend it as a means of enhancing your knowledge and having some fun while doing it.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 3 PMRoyal Mail’s Oct. 1 definitive meets new international standard rate

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 12 PMPostcrossing meetup Oct. 9 at U.N. headquarters

-

Postal Updates

Oct 7, 2024, 5 PMUSPS plans to raise postal rates five times in next three years

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest