US Stamps

Errors, freaks, oddities and blunders: from the sublime to the ridiculous

By Fred Baumann

“Stamps that have some major, consistent, unintentional deviation from the normal are considered errors.” So begins the brief paragraph on that complex subject that you’ll find — and that all interested collectors would do well to read — in the introduction to the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue.

“Errors include, but are not limited to, missing or wrong colors, wrong paper, wrong watermarks, inverted centers or frames on multicolored printing, inverted or missing surcharges or overprints, double impressions, missing perforations and others.”

Ending this definitive sentence with “and others” might sound as dismissively imprecise as et cetera, but it leaves the definitional door ajar for a good reason. There are more one-of-a-kind errors in philately than most of us would dream of, and many of these do not have simple names or helpful explanations. Illustrated nearby are two such United States stamp errors, one well-known, the other much more scarce.

The former is the perforated 5¢ carmine Washington error of color. Most of these errors were purchased, used, canceled, delivered and discarded as ordinary 2¢ stamps without a second glance. Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries provides a helpful summary of the error’s genesis:

“During the course of production of the normal 2c plate No. 7942, three positions were noted to be defective. The plate was sent back to the siderographer, who burnished out the three positions and mistakenly re-entered them using a transfer roll for the 5c stamp. The error passed unnoticed and the sheets were issued to the public both Perf 10, Imperforate and Perf 11 (Scott 467, 485 and 505). The imperforate is by far the rarest of the three.”

Shown nearby is the rare imperforate version few collectors have ever seen (Scott 485), an unusual horizontal strip of three, se-tenant between two normal 2¢ Washington definitives, with parts of two other adjacent stamps on either side. Estimated at $20,000, Siegel sold this strip in an Oct. 28, 2008, auction for $16,500, plus the buyer’s commission.

Adjacent to it is my attempt to reproduce the appearance of the impression on the 5¢ Washington transfer roll (reversed, and in light gray to mimic polished steel) in which the similarity of the reversed inverted “5” to a “2” is quite striking. Like most errors — human and stamp — it is all too easy to see how this one could have happened.

The same is true of another red error, also sold by Siegel. Shown are a normal mint 1913 2¢ carmine Panama-Pacific International Exposition commemorative depicting the Panama Canal (Scott 398) and a second example that looks quite different.

Because of its crystalline shine and the darker shade imparted to the ink and paper alike, the stamp at right is referred to as a varnish ink variety. According to Siegel, its “distinctive color and impression” suggest that “the ink must have been mixed with a component that caused this distinctive variety,” for which it received a Professional Stamp Experts, or PSE, certificate in 1995, although it is neither mentioned nor listed in Scott. Estimated at $500 to $700 in the 2007 auction of the Saddleback Collection of U.S. errors, it sold for $900, plus commission.

EARLY U.S. STAMP ERRORS

Stamp errors exist throughout philatelic history. The first U.S. regular issue of 1847 (Scott 1-2) avoided them, but the 1851-57 issue that followed has several denominations known to have been printed on both sides — an error of frugality caused by a desire not to waste paper by discarding substandard printing.

The same thrifty spirit resulted in the creation of double impressions, in which a stamp too lightly printed to pass muster was given a second trip through the press to give a stronger imprint. It’s all but impossible to align the paper with perfect precision, the result being an error in which two inked impressions, slightly offset, occupy the same stamp.

Shown here is one of the earliest of these, and one of only two authenticated examples known of the 1857 3¢ dull red, type III double impression (Scott 26e). Siegel sold this used single for $8,500 in 2012. The second example is on an 1859 cover from New Orleans to Boston.

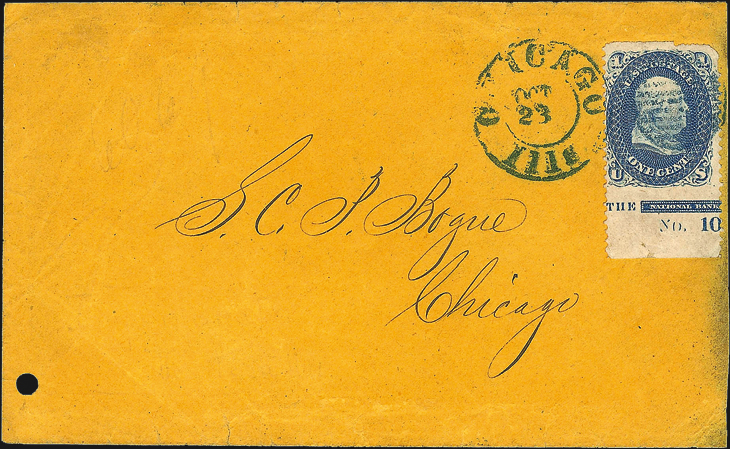

The 1857-61 issue was the first U.S. issue to be regularly perforated, which gave rise to a new and vast family of stamp errors, one of which franks the Chicago drop mail letter shown nearby.

Its particulars also reflect the problems of such a rarified collecting specialty. As the Siegel auction describer put it, “In his book The United States 1c Franklin, 1861-67, Don Evans notes that the Scott Catalogue lists a vertical pair, imperforate between, but that its origin and present location are unknown to him. The only example of this stamp imperforate horizontally that he records is the cover offered here. [Lester] Brookman notes a used pair imperforate horizontally, but it has never been certified by the Philatelic Foundation and may be lost to philately.”

Although two imperforate errors are recorded, the whereabouts of neither are known. The only current evidence for a vertical pair, imperforate horizontally of the 1861 1¢ Franklin (Scott 63d) is this used imperforate bottom margin example. Ex-Ishikawa, it was estimated at $5,000 to $7,500 in part 1 of the sale of the Drucker Family collection in 2002, where it sold for $9,000.

In view of the uncertain survival of the discovery examples upon which its listing is based, it has a dash in place of a value in the Scott catalog, which means “that information is either lacking or insufficient for purposes of establishing a usable catalogue value.”

COLOR ERRORS

A new U.S. stamp error variety came into being with the arrival of bicolored high-denomination stamps of the Pictorial issue of 1869, which required two passes through a press to print the two colors of the finished stamp.

To my eye, one of the most striking stamps of this issue is the 30¢ ultramarine and carmine Shield and Eagle (Scott 121). It is shown nearby with the elusive flags-inverted error (121b).

Estimated at $1 million in the 2013 Siegel auction of the Beverly Hills collection of U.S. inverts, this invert sold for $600,000, plus premium. In the auction catalog, it was described as the finest of the seven recorded unused and the only example known with original gum.

The 2016 Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers values unused examples of Scott 121b with gum at $750,000, and unused examples with no gum at $300,000.

Dramatic and striking, the 1869 inverts are classic U.S. errors that can have truly exceptional value. But a U.S. stamp can still be a valuable error of color even if it is monochromatic.

Shown nearby are three 1893 Columbian commemoratives: the 1¢ deep blue (Scott 230), the 4¢ ultramarine Fleet of Columbus (233), and the 4¢ deep blue error of color (233a) sold by Siegel in November 2013 for $11,000, plus commission. The 2016 Scott U.S. Specialized catalog lists the error at $17,500 unused and $16,500 used.

As the images suggest and Siegel confirms, “The 4¢ Columbian color error was caused by the use of a wrong batch of ink, and spectrographic analysis has shown that the blue inks of the 4¢ color error and 1¢ Columbian have the same components.

“Stamps from at least two panes reached collectors, and the few cancelled examples indicate that stamps used by the public came from additional panes. It is likely that a number of full sheets were printed using the wrong ink, and most of the stamps have simply been lost to philately.”

With the explosion of multicolored U.S. stamps during the last 50 years, there have been more opportunities for errors of color to occur, with collectible and eye-catching consequences.

Two of my favorites make up an attractive Field of Dreams-style combo nearby: the black omitted 1969 6¢ Professional Baseball commemorative at left (Scott 1381a), and the engraved black and blue (engraved) omitted 1974 10c Rural America commemorative at right (Scott 1506a). In the last 13 years, Siegel has auctioned eight mint examples of the former at prices from $200 to $525 (the example shown sold for $475 in 2014), and four examples of the latter for $180 to $350.

PERFORATION ERRORS

Modern perforation errors are a realm where precise descriptive terminology matters, and where items that might look alike can be vastly different in terms of significance and value, as witnessed by the 14¢ Sinclair Lewis stamps nearby.

I was a green lot describer at an auction firm in the western suburbs of Detroit when an excited collector was the first to regale me frantically with news of this new Great Americans perforation error that he had just purchased in a pane of 100 at a local post office. His 100-stamp pane had 10 imperforate-between horizontal pairs (Scott 1856c). He left with visions of wealth, but within a week I had heard a dozen similar tales, and soon read about them in other locales across the country. Somehow, no one noticed an entire column of missing perforating pins for a considerable period of time, during which these Sinclair Lewis imperforate-between errors poured out 10 to the pane.

The Scott Catalogue of Errors on U.S. Postage Stamps by Stephen R. Datz now lists the quantity of these in collector hands as “several thousand pairs,” and values them at $8. Even at half that value, $40 in errors is a nice but modest premium on a pane with a face value of only $14.

A vertical pair, imperforate horizontally surfaced as well (Scott 1856b), in which there was no evidence of horizontal perforations either between the two stamps, or at their upper or lower margins. Datz noted that 200 to 250 pairs had been reported, which boosted their value to $100.

A vertical pair, imperforate between also came to light (Scott 1856d), but Datz listed the quantity as no more than 15 to 20 pairs reported. These he pegged at $1,500, with that figure shown in italics, as “the editor’s estimate when no precise information is available, such as newly discovered or infrequently traded errors. They should be regarded as tentative and subject to fluctuation.”

Last and most eye-catching, however, is the full pane shown nearby, with a top row of the 14¢ Sinclair Lewis, a second row below it with bits missing from the lower edge of the portraits and denomination, and the remaining 80 stamps in the pane with no printed designs at all. This is a color error rather than an error involving perforation.

This pane, from the William S. Floyd collection of modern U.S. errors, was offered by Shreves Philatelic Galleries in its Collector's Series Sale 55 on March 7, 2003, with an estimate of $1,500 to $2,000, and sold for $1,000 plus commission, or the equivalent of $100 per vertical strip of 10. Scott lists it as the “all color omitted” variety of the stamp (Scott 1856e), with a dash instead of a value.

If this discovery pane remains intact and no others are reported, then it is the unique example of this error until and unless its columns are separated. If that pane is again offered to a more receptive floor of bidders, there’s no telling how much it might fetch.

BACK-OF-THE-BOOK ERRORS

For the record, U.S. philatelic errors also extend to the back-of-the-book, where more than a few additional examples are to be found. These include the 1989 25¢ Shuttle at Space Station stamped envelope with the ultramarine “USA 25” omitted, leaving only the foil hologram (Scott U617a), as shown nearby. Offered in the 2007 Siegel auction of the Saddleback collection of U.S. postal stationery, it sold for $350, plus commission.

FREAKS AND ODDITIES

Revenue stamps include their share of errors, too, such as this 1871 $5 blue and black second issue invert (Scott R127a), with an 1871 manuscript cancel, hammered down by Siegel in 2008 for $5,750.

The Scott catalog definition of errors tells collectors what they are not, too: “Factually wrong or misspelled information, if it appears on all examples of a stamp, are not considered errors in the true sense of the word. They are errors of design. Inconsistent or randomly appearing items, such as misperfs or color shifts, are classified as freaks.”

Shown here are two relatively common U.S. definitive perforation freaks of the 1973 10¢ Jefferson Memorial (Scott 1510) and 1975 2¢ Speaker’s Stand from the Americana series (1582). Their appearance is striking, but there is no end to the possible varieties, and nothing indispensible to the stamp has been left out, even if the horizontal perforations are misplaced.

Most such U.S. freaks can be acquired for relatively modest sums, especially through the regular auctions and advertisers that appear in The EFO Collector, journal of the Errors, Freaks and Oddities Collectors Club. Dues are $20 a year in the United States, $37 elsewhere.

Some items that could rightly be regarded as incomplete errors are correctly classified as freaks: stamps with incompletely punched perforations, or with only the faintest traces of an otherwise absent color, for instance. These are not errors, and that is reflected in the prices for them.

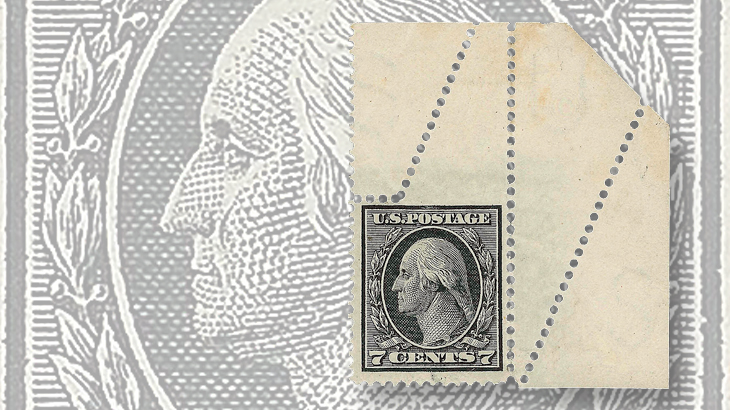

Other freaks are one-of-a-kind, including so-called crazy perforations, which often occur when there is a fold-over in the stamp paper as it passes through the perforating machine, leaving a bizarre pattern behind. An example of this is the top-right corner example with selvage of the 1914 7¢ black Washington (Scott 407), in which a fold-over through it caused wild perforations at the margin and a partial imperforate design at the top. Siegel sold this example in 2003 for $160.

If the frontier between errors and freaks is sharply drawn with fixed rules and requirements, the boundary between freaks and oddities seems considerably more porous, and your own sense of what is interesting and collectible might be your most reliable guide.

Two examples are shown nearby of what strike me as United Kingdom oddities. On the left is a 1955 1-shilling bister brown Wilding definitive of Queen Elizabeth II with a doubled or blurred design. There’s nothing remarkable about the color, but the vertical blurring appears to give the queen the eyebrows and mustache of Groucho Marx.

The other stamp is a 26-penny William Salesbury commemorative from a 1988 set honoring the 400th anniversary of the Welsh Bible. The chaotic appearance undercuts the solemn subject, with the entire design shifted upward, the orange color and text off to the right of the rest of the design, the queen’s profile bisected, and much more.

BLUNDERS

Last is a catch-all category that is sometimes referred to as design errors, or errors in stamp design. These are stamps burdened with blunders in the precise sense of that word, a blunder being “a gross error or mistake resulting usually from stupidity, ignorance, or carelessness.” Try to honor a popular American poet with her face next to a verse she never wrote, as in the U.S. Maya Angelou commemorative issued this year (Scott 4979)? Yeah, that’s a blunder.

It’s a stamp where all the men and women responsible for printing and issuing the stamp did their job — everyone, that is, except whomever designed it. If the spelling is wrong, the map is inaccurate, the portrait shows the wrong guy, or Christopher Columbus is peering through a telescope that hadn’t been invented yet, that’s a blunder.

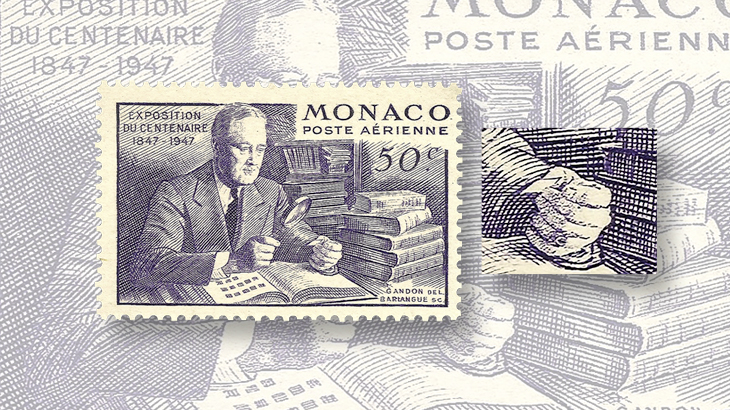

One of my favorite blunders is the 1947 50-centime Monaco airmail stamp (Scott C16) showing Franklin D. Roosevelt, America’s foremost philatelist, securely grasping a stamp with the thumb and the other five fingers of his left hand.

Giving the president 11 digits is bad enough, but having America’s best-known philatelist pick up a stamp by pinching it with his oily fingers? Come on, Monaco — where did you leave his stamp tongs?

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers