US Stamps

Ever-popular classic Hawai`i stamps portray islands’ stormy history

By James L. Haley

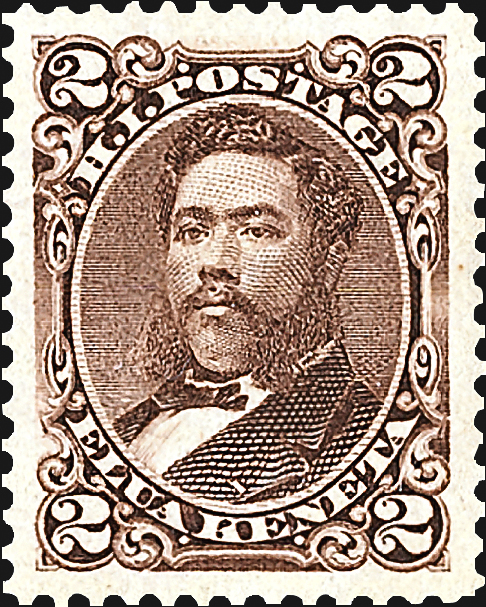

In the world of stamp collecting, the Hawai`i “Missionaries” (Hawaii Scott 1-4) have long been at the forefront of celebrated classics, but it is the later (and much more affordable) engraved issues that tell the story of the kingdom’s colorful history.

Capt. James Cook was possibly the first European to visit the islands, in 1778, but their culture had existed for centuries as an outpost of Polynesian war, kapu (taboos) and human sacrifice.

After 30 years of relentless conquest, King Kamehameha I unified the islands in 1810, but survivors who fled his massacres brought American missionaries back to the islands only 10 years later.

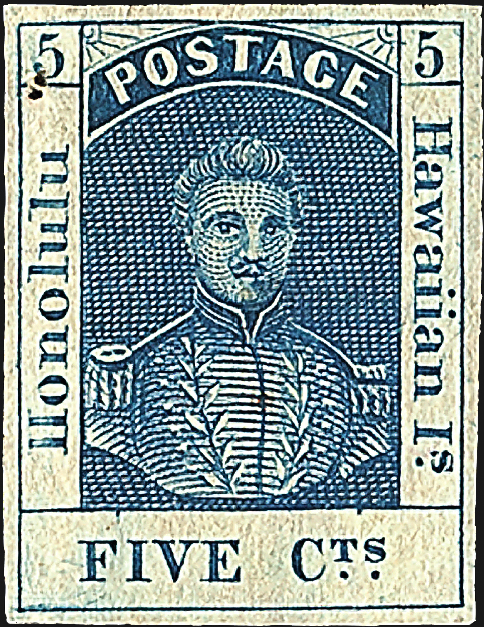

In important ways, the country’s modernization began with King Kamehameha III (shown on Scott 5), who was a figure both transitional and tragic.

Born in 1813, before the missionaries’ arrival, he gloried in his ancestral privileges and life-and-death power. He was the islands’ longest reigning monarch, from 1825-54.

Women in Hawai`i, however, could be very powerful, and when Kamehameha’s mother, Queen Keopuolani, and his stepmother, Queen Ka`ahumanu, both converted to Christianity, they dragged him along with them to their new religion.

He attempted suicide when missionaries prevented him from marrying his sister, Princess Nahi`ena`ena, an alliance that in the native culture was not just acceptable but a brilliant match.

Eventually submitting to Christian obedience, Kamehameha III granted his people a declaration of rights, a liberal constitution and a legislature, and donated more than half his personal lands to allow, for the first time, ownership by common people.

Kamehameha III had no children who survived, and thus he adopted the children of his half-sister and of his prime minister, Kina`u. Her husband, Mataio Kekuanao`a (Scott 34) was the father of Alexander Liholiho (Kamehameha IV, Scott 32) and Lot Kapuaiwa (Kamehameha V, Scott 33).

Lot was actually the elder of the brothers, but was demoted for his lack of kingly temperament.

As a student in the missionary-run Royal School, he was 12 when he impregnated his cousin, 14-year-old Princess Abigail Maheha. He was whipped; she was forced to marry her mother’s gardener and exiled to Kaua`i. In a rage, young Lot swore never to marry, and he never did, performing an important part in bringing down the dynasty.

With the death of Kamehameha III in 1854, Alexander Liholiho ruled for nine years as Kamehameha IV. He married the beautiful Emma Na`ea and produced a son and heir. The prince died at age 4, however, followed a year later by the grief-stricken king.

As identified in the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue, the shattered Emma renamed herself Kaleleonalani (Scott 49), meaning “Flight of the Royal Ones.”

The bad-tempered Lot then reigned for nine years as Kamehameha V (Scott 33), withdrawing his uncle’s liberal constitution and assuming more direct power, though he exercised it wisely and became known as the “Last of the Great Chiefs.”

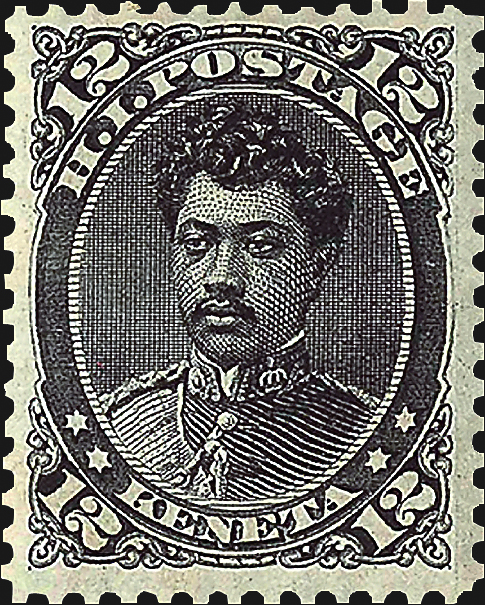

By blood, next in line to the throne was Prince William Lunalilo (Scott 48), but under the constitution the legislature was to select the monarch when there was no direct heir. Also in the running for king was High Chief David Kalakaua, who was not in the royal line but was ambitious, and had mastered American-style politicking.

Lunalilo won easily; he was actually higher-born than the two Kamehameha brothers who protected their positions by blocking his marriage to their sister, Princess Victoria Kamamalu (Scott 30). This prevented Lunalilo from having children who would outrank the brothers, and thus also helped to doom the Kamehameha dynasty.

King William Lunalilo died without heirs after only one year, throwing the election again into the legislature.

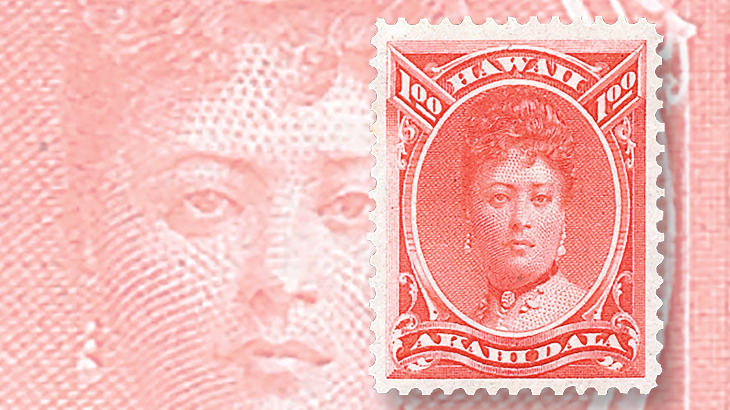

There were two contenders: Dowager Queen Emma, who enjoyed massive popularity among the common people, and, once again, High Chief David Kalakaua, who curried favor among the lawmakers until he was assured of the election in 1874.

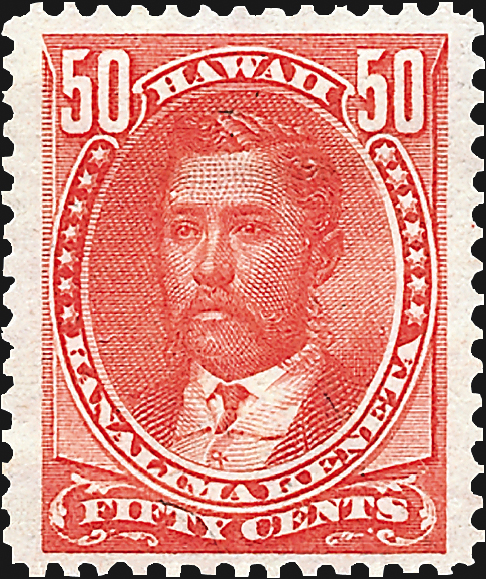

Emma received only six votes while Kalakaua received 39, and he was proclaimed king (Scott 35). Honolulu erupted in three days of rioting that was quelled only by the intervention of British and American marines.

As one of his peace offerings, King David had Emma depicted on the $1 rose red (Scott 49), the highest Hawai`ian denomination ever issued. Emma eventually accepted Kalakaua as king, but never spoke to his wife, Queen Kapi`olani (Scott 41). She had been Emma’s lady-in-waiting at the time of little Prince Albert’s death, and Emma blamed her bitterly.

Emma, however, was not Kalakaua’s greatest problem; he himself, more than any other monarch, did the most to fumble away the country’s independence.

Once on the throne, he gratuitously stripped royal rank from the two remaining Kamehameha descendants, Princess Bernice Pauahi and Princess Ruth Ke`elikolani.

It was a stunningly stupid move, for Princess Ruth owned nearly 10 percent of the country. She also was the adoptive mother of Kalakaua’s younger brother, Crown Prince William Pitt Leleiohoku (Scott 36), and he was her heir.

When Leleiohoku died unexpectedly at age 23 in 1877, Kalakaua was next in line to inherit her vast fortune. However, having been repeatedly insulted, the formidable Ruth took him to court and recovered her wealth, leaving Kalakaua to beg and borrow from American sugar barons — debts that proved to be his undoing.

When the throne finally passed to Kalakaua’s sister, Lili`uokalani (Scott 52) in 1891, the American-Hawaiian business community was well-advanced in plans to annex the kingdom to the United States.

They accomplished their coup two years later with the help of American Marines from the USS Boston, who acted with a wink and nod from the Republican Benjamin Harrison administration.

Previous stamp issues depicting royalty (beginning with Scott 53) were overprinted with “Provisional Govt.” and a year date by the resulting junta.

Harrison was soon out of office, and President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, was mortified by the unsavory events in Hawai`i. It took a combination of events, including the next Republican administration under William McKinley, the growing threat of Japanese militarism and events of the Spanish-American War, before the islands were finally annexed to the United States, over the nearly universal protest of the native peoples.

While Kalakaua’s mismanagement as monarch went a long way toward losing the country, he did understand the propaganda value of postage stamps.

Kalakaua was only 26 in 1863 when Kamehameha IV appointed him postmaster general of the kingdom.

In order to increase Hawai`i’s prestige abroad, Kalakaua began ordering those beautiful engraved issues from the National Bank Note Co. in the United States — stamps that now recall a tragic national history.

James L. Haley is the author of Captive Paradise: A History of Hawai`i, published in 2014 by St. Martin’s Press.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers