US Stamps

Exploring United States postage stamp essays and proofs

Like most collectors, I reached a point in my philatelic pursuits where filling spaces in an album just wasn’t enough anymore.

Looking for something to embellish my pages, I stumbled upon a classified advertisement in Linn’s Stamp News in 1972. It was a three-line ad for essays and proofs offered by a man in Coram, N.Y., named Falk Finkelburg.

He opened my eyes to a whole new area of collecting and became my mentor for more than 20 years.

My inaugural Linn’s column is intended to familiarize you with the two basic types of United States essays and proofs. Future columns will deal with each of these types in depth, and I plan to share some great stories about this area of philately that I have accumulated or experienced over the years.

Starting with the first issues in 1847 and continuing through 1894, all U.S. postage stamps were produced by private banknote companies.

From time to time these companies would compete for the postage stamp contract. They would supply the U.S. Post Office Department with production proposals and examples of their work.

An example of an engraved design that was accepted by the Post Office Department for production is considered a proof. It is an actual representation of what will become the issued postage stamp.

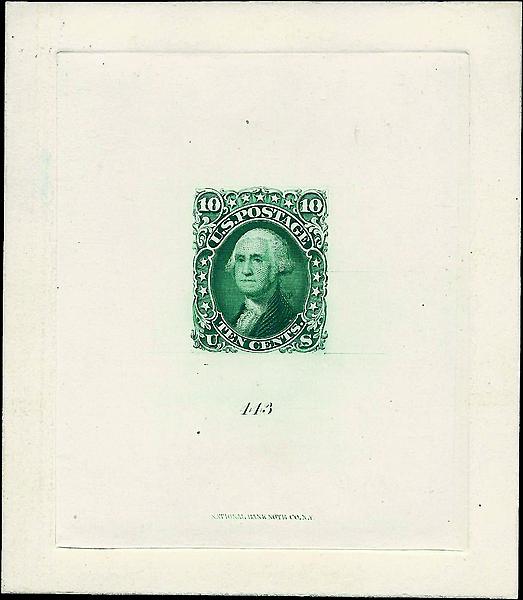

Figure 1 shows a proof of the 1861 10¢ green George Washington stamp (Scott 68).

An engraved design that requires modification or was rejected by the department is an essay or rejected design.

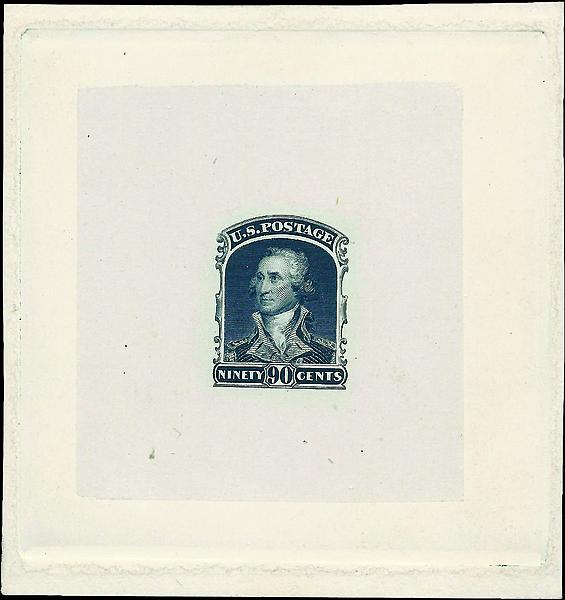

Figure 2 shows an essay for the 1861 90¢ blue George Washington stamp (Scott 72).

Now that you have seen these two final outcomes for a design, I will trace the steps it took to reach the end result.

Both examples started out as a concept or design of what the finished stamp might look like. At this stage of the process, the design would be in the form of a drawing or composite of pencil, ink, wash and stock engraved elements.

Once this design had been finalized, it was put into the hands of a master engraver to execute the image in reverse on a soft block of steel.

Upon completion of the engraving, an impression of the image was pulled on India paper for approval by the Post Office Department.

If the image was approved, it became a proof of the final design. If enhancements were requested, it was an essay of the image at this point of the process.

Once the enhancements were completed, another impression was pulled and, if approved, it became a proof of the completed design.

The completed and approved soft steel block is the die, which was then hardened. The image on the hardened die was taken up on a steel transfer roll, and the roll was used to repeatedly transfer the design to the plate that would be used to print the stamps.

The image in Figure 1, a die proof, was produced by a steel die created by the National Bank Note Co. of New York City in 1861 as part of the new contract for postage stamps during the early months of the American Civil War. The green color was the specified color for the 10¢ value. Beneath the design you will note the number “443,” which is the die number National Bank Note Co. assigned to this die for internal identification purposes.

At the bottom of the die sinkage is the imprint for the National Bank Note Co. This imprint was only applied to a completed approved die.

The image in Figure 2, a die essay, was produced by Toppan, Carpenter & Co., the then-current stamp contractor, in 1861, when competing for the same contract for new postage stamps. They simply took the existing die for the 1860 90¢ George Washington issue, which they had produced, inserted the numerals “90” into the tablet at the bottom of the design, and submitted it with their contract proposal. They lost the contract to National Bank Note Co., and stamps were never produced from this die.

My next column will explore the many different types of proofs that exist for United States Postage Stamps.

James E. Lee has been a full-time professional philatelist for over 25 years specializing in United States essays and proofs, postal history and fancy cancels. He may be reached via e-mail at jim@jameslee.com, or through his website, www.jameslee.com.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers