US Stamps

How to transform younger, specialized collectors to expertizers

U.S. Stamp Notes by John M. Hotchner

I remember a phrase from my youth that will probably resonate with many Linn’s readers, “Beggars can’t be choosers!”

What has that to do with philately?

It applies to the fact that there are never enough willing and competent people to do all the things that need doing. There are not enough collectors to reach out to encourage and mentor those new to the hobby, not enough new exhibitors coming into the field to fill all the frames at stamp shows, and not enough people willing to serve as officers in clubs and societies to bring to life the great ideas proposed to serve the membership.

And of interest to this column, there are not enough younger people willing to offer their services as expertizers. Most expertizers have volunteered in their later years after decades of experience in their specialty areas. However that was not how I started.

One day 34 years ago, I received an invitation from the American Philatelic Society to consider joining the expertizing committee based on my then 10 years of experience as a Linn’s contributor, articles on errors, freaks and oddities (EFOs) in the United States Stamps Society’s journal the United States Specialist, and exhibits I had prepared. With some trepidation, I said yes and laid out the areas where I thought I could contribute: 20th-century United States and worldwide printing varieties.

A year or so ago, a colleague suggested that there should be a test to determine if applicants are qualified to be an expertizer in a given branch of the hobby. In a perfect world, I would love the idea. But beware the law of unintended consequences: Make it more difficult to become an expertizer, and the result is likely to be even fewer expertizers.

And I am not at all sure that the problem is lack of competence on the part of today’s expertizers, so much as a paucity of collectors in the pipeline who will become tomorrow’s expertizers.

Looking back, I am certain that when I began I would not have passed an objective test. The fact was I didn’t know nearly enough to function as an expertizer on my own, and this became painfully obvious when I began doing the work.

I was lucky in that the sainted George Brett was the primary expertizer in my chosen field, and he was willing to mentor me. One of the benefits of having more than one person look at submitted material, which expertizers call “patients,” was that I was able to offer opinions and Brett was able to critique them: Had I noticed this? Had I considered that? Would another explanation for why a patient was or was not genuine make more sense?

In effect I was an apprentice for the next almost 20 years until Brett passed away in 2005. During that time, I built my own reference collection (still a work in progress), purchased books, subscribed to society journals, and read widely in older publications.

Being young and too confident when I began, I am now older, much more experienced and less confident. That was the value of being mentored.

And that is the model I would like to see more of. Instead of waiting for senior philatelists to volunteer as expertizers, I would like to see a more formal apprenticeship program where younger specialists are paired with an experienced expertizer to learn both theory and practice with live patients.

I believe that the trade can be taught, and my hope would be that we could identify and invite younger collectors who have become specialists and teach them the art and science of expertizing, including some formal classroom training.

Today’s experts could be talent scouts for such a program, though volunteers should be welcomed also. This makes much more sense to me than subjecting the relatively few volunteers to the possibility of failing a test.

With an apprenticeship program, expectations of a participant would be reasonable. When I first began expertizing, I almost felt like I was thrown into the deep end of the pool. I was expected to know it all, and I plainly did not.

Allowing collectors new to the field of expertization a period of familiarization, learning and practice would be helpful. They would not have to know everything right away and be correct every time.

As siblings sometimes do, one of my older sons used to tease the youngest because he hadn’t mastered what the older son had learned in math. I was proud of the youngest who responded, “I’m only 6 … I’m not supposed to know that yet.”

What a sense of reality and even humility that answer conveyed. And isn’t it true of all of us as we develop specialties? Most of us have a sense not only of what we know, but what we don’t know. And that is OK because knowledge comes with experience.

A reverse image and a warning

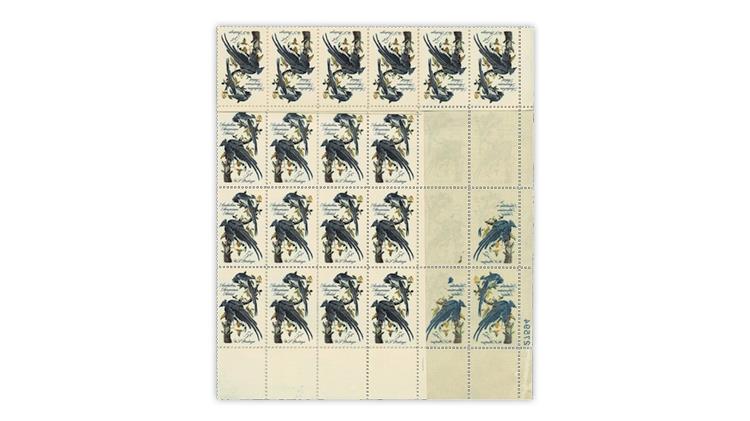

Shown in Figure 1 is a folded-over pane of the 1963 5¢ John James Audubon issue (Scott 1241) with the back of the stamps showing in the lower right. Reverse images of the stamp design are printed on the gum on one full stamp and parts of three others. This is a genuine production error.

It could happen in the era of this stamp (and later) on sheet-fed presses. Here’s how. Ink is deposited on the plate, in this case a Giori press plate, meaning that all colors are on the same plate. Then a sheet of paper that will carry 200 images of the new stamps (four post office panes of 50) is inserted into the press.

An impression roller pushes the paper against the plate under tremendous pressure, and the image is transferred to (printed on) the front of the paper.

But if a misfeed of paper occurs, the plate may deposit some of the images on the impression roller, which will in turn deposit the images on the gum side of the next sheet through the press. That image will be clear, consistent and complete.

Now we get to the beware part.

I have recently seen an EFO price list that includes several examples of what are presented as genuine printed-on-reverse errors that are at best ink transfers due to stamps stored under pressure in humid conditions. Four examples are shown in Figure 2: the 1972 8¢ Colonial American Craftsmen block of four, the 1959 8¢ World Peace Through World Trade commemorative, the 1954 1¢ George Washington definitive of the Liberty series, and the 1937 2¢ Army stamp.

Genuine examples of this type of error will always be exact matches to the stamp on the front, as shown in Figure 1. Clearly the three single stamps in Figure 2 do not qualify.

But what about the 8¢ Colonial American Craftsmen plate block? It is also not the error. Recall I said that the genuine error can only occur on sheet-fed press stamps. This is a web-fed product, and the image, though matched to the stamp on the front, is not consistent or complete.

At worst these examples are intentional creations to mimic the error. At best they are accidents. In any case they happened after production and should not be represented as errors or genuine varieties.

I will throw in a related caution. The 13¢ 13-Star Flag Over Independence Hall pair, shown front and back in Figure 3, is from a coil roll that had stuck together. Stamp paper is composed of layers, and, in this case, the roll being pulled apart split the paper.

There is a gummed layer over the design as seen in the pair at top showing the front, and that layer is missing from the back, as can be seen on the pair at bottom in Figure 3. When viewed from the back, this appears to be a freakish reverse printing. The first time I saw one of these was many years ago, offered with a fancy price tag in an ad.

In reality they are simply damaged stamps that not even the U.S. Postal Service would accept as valid postage.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 3 PMRoyal Mail’s Oct. 1 definitive meets new international standard rate

-

World Stamps

Oct 8, 2024, 12 PMPostcrossing meetup Oct. 9 at U.N. headquarters

-

Postal Updates

Oct 7, 2024, 5 PMUSPS plans to raise postal rates five times in next three years

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest