US Stamps

Identifying 4¢ blue Columbian errors

U.S. Stamp Notes – By John M. Hotchner

A friend recently wrote to me with the following question: “Attached are scans of a 4¢ Columbian that’s languished in a cigar box for many years, and which to me looks like it just MIGHT be the Blue color variety (rather than the normal Ultramarine) — Scott 233a.

“I well understand that if genuine, it would be one of those great rarities — particularly since Scott notes that most used examples of this stamp are in somewhat ragged condition. I see that one of these, with tears, etc. was being offered on eBay for $2,999.99. Scanning through all the other 233s being offered on eBay right now, mine certainly looks BLUER than any of those illustrated (even discounting scanner variations)

“I know this is one of those items that would need an expertizing certificate to show it being genuine, but I’m asking your thoughts in advance of that — don’t want to waste the time and money otherwise.”

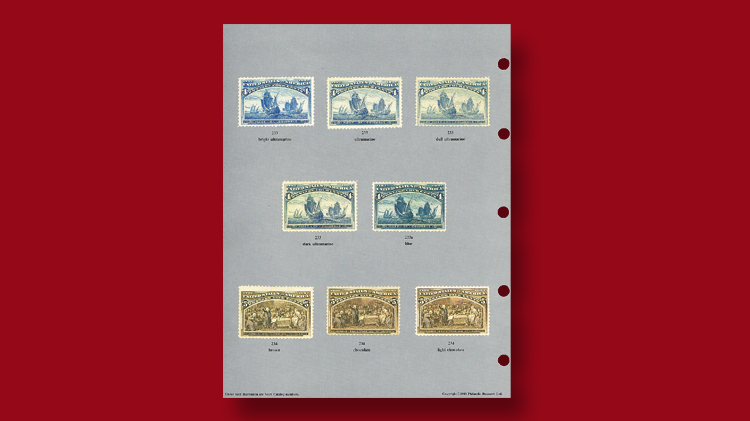

The scanned image of the 4¢ Columbian my friend was writing about is shown above, along with a normal 1¢ blue Columbian. I agree that it is not a normal ultramarine example, but I don’t think it qualifies as the blue error. Beyond that it’s hard to know where to start in answering this question, but let’s begin with the listing in the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers.

Scott 233 is the 4¢ Columbian, for which the normal color is listed as ultramarine. Listed variants of this color are dull ultramarine and deep ultramarine. The 2018 Scott U.S. Specialized values the normal stamp and these shade varieties at $50 mint for hinged examples and $8 used.

The error is listed as Scott 233a, “4c Blue (error)” with a hinged value of $17,500, and a used value of $16,500. A note below the listing begins, “No. 233a exists in two shades.” Scott does not further identify what these shades.

The listing continues, “No. 233a is valued with small faults, as almost all examples come thus.”

R.H. White, in his monumental Encyclopedia of the Colors of United States Postage Stamps, Vol. II (1981), illustrates the known colors as shown on page 6.

White quotes early 20th-century philatelic scholar Lester Brookman as saying,

“…The [blue] shade is very different from the normal ultramarine …The usual statement that it is like the color of the 1¢ is not exactly accurate. It is much more like the 1¢ than it is the normal 4¢ but the color seems to be … more lively … than that of the 1¢.”

How many examples of the 4¢ blue Columbian error exist? There is no reliable answer. The original find was a single mint sheet of 100, but subsequent finds of used examples indicate that several sheets of the error were not recognized, and the stamps were used on mail. Thus, it is possible that previously unidentified examples may lurk in old collections.

With that background, let’s make a few observations. First and foremost, a collector should NEVER offer or buy a 4¢ Columbian represented to be the blue error (Scott 233a) unless it has a certificate with a photo and description that exactly match the stamp. It does not matter how great a bargain it seems to be.

Why is this? Unless a collector has handled many examples of Scott 233, or has a reference example of 233a, or a high-quality color photo, it is purely a guess as to whether the stamp in hand is a 233a.

Given the values involved, it is simply too easy to diagnose a stamp in hand as what the collector wishes it to be, with whatever evidence the collector may be able to find “on the fly."

Other factors at play with used stamps are that the aging of the paper, happenstance contact with strong light or chemicals, or specific efforts to alter can result in subtle changes of color that may push the color toward the target variety. For these reasons, expertizing is essential.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

As I’ve said many times in this column, it is not possible to positively expertize from a scanned image. The actual stamp must be viewed by the expertizer.

Sometimes it is possible to rule out a stamp based on a scanned image, and, in the case of the stamp my friend wrote about, it is clear that he would not have spent his money wisely to have the stamp expertized.

In fact, given the costs involved, it is not a good idea to submit such a stamp “cold” for expertizing as the chances of it being genuine are small.

Instead if you have a competent dealer in your local stamp club, or can talk with one at a local show or bourse, show it to him and ask him if he thinks it has a better than 75-percent chance of being found genuine.

If you can match your stamp to a reliable photo of an expertized Scott 233a in a reference book or commercial auction and you can get a dealer recommendation, then the stamp may stand a reasonably good chance of passing muster.

This brings up another bit of correspondence from a Linn’s reader, who asked, “Could you send me the basic expertizing fees? Do they go by catalog value? What is the cost if the stamp is a fake?”

Fee structure can be complicated, and fees can change periodically, so I do not have a cheat sheet that explains the fees for each of the expertizing organizations.

My suggestion is that if you want to determine the fee that applies for a specific stamp you are considering submitting begin by searching online for the auction house, then find its fee structure, what it is based on, and under what circumstance the auction house will refund all or part of the fee.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers