US Stamps

How postal history tells the story of the atomic bomb

By Ken Lawrence

The conflict that became World War II gained momentum gradually, starting with Japan’s aggression against China in 1931; Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935; and Nazi Germany’s remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936, followed by the annexation of Austria and subjugation of Czechoslovakia in 1938.

The German invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, integrated and escalated those earlier conquests to the level of global conflict, which continued until Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allies on Sept. 2, 1945.

In almost symphonic harmony with those dates, the history of the atomic bomb began with Albert Einstein’s Aug. 2, 1939, letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, advising him that such a device could be built, and reached its climax with the Aug. 6 and 9, 1945, devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, respectively, by uranium and plutonium fission bombs.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

The coda came less than a year later, when American armed forces detonated two atomic bombs at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

Sometimes only allegorical compositions can convey with appropriate reverence the enduring heritage of war. Homer teaches us about the Greeks’ secret weapon at Troy. The climax of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture is performed by actual cannons being fired, followed by the joyful bells of Moscow churches pealing in relief and celebration as Napoleon’s army retreats.

Whose muse will script America’s secret weapon of 1945? A comparable World War II orchestral composition might culminate with an explosion, a flash brighter than the sun, and a mushroom cloud. Future generations might perform Norman Corwin’s 1945 CBS radio epic On a Note of Triumph, highlighted by this excerpt:

Lord God of trajectory and blast

Whose terrible sword has laid open the serpent

So it withers in the sun for the just to see,

Sheathe now the swift avenging blade with the names of nations writ on it,

And assist in the preparation of the ploughshare. …

Lord God of test-tube and blueprint

Who jointed molecules of dust and shook them till their name was Adam,

Who taught worms and stars how they could live together,

Appear now among the parliaments of conquerors and give instruction to their schemes:

Measure out new liberties so none shall suffer for his father’s color or the credo of his choice:

Post proofs that brotherhood is not so wild a dream as those who profit by postponing it pretend:

Sit at the treaty table and convoy the hopes of the little peoples through expected straits,

And press into the final seal a sign that peace will come for longer than posterities can

see ahead,

That man unto his fellow man shall be a friend forever.

Corwin’s prayer has not yet been answered — nuclear weapons still menace us three quarters of a century after their conception while headlines blare news of intractable strife — but his sentiments are no less worthy today.

My medium here is not music or poetry, but postal history. Let us see whether this less exalted but more personal and literal approach can adequately serve the purpose, not only to reconstruct the history but also to honor its memory.

For the United States, with the exception of the date and location of the June 6, 1944, D-Day invasion of Europe, the atomic bomb was the greatest secret of the war. Secrecy has severely limited collectors’ ability to acquire postal relics of this momentous history, and has restricted our access to information that gives us a complete understanding of their significance. Even today, three quarters of a century later, previously undisclosed aspects of atomic bomb postal history are coming to light for the first time.

Albert Einstein’s Letter to FDR and its Consequences

Einstein wrote:

Some recent work by E. Fermi and L. Szilard, which has been communicated to me in manuscript, leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future. Certain aspects of the situation which has arisen seem to call for watchfulness and, if necessary, quick action on the part of the Administration. I believe therefore that it is my duty to bring to your attention the following facts and recommendations:

In the course of the last four months it has been made probable — through the work of Joliot in France as well as Fermi and Szilard in America — that it may be possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated. Now it appears almost certain that this could be achieved in the near future.

This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable — though much less certain — that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. …

The letter went on to warn that physicists in Nazi Germany were conducting similar experiments. It suggested that the president establish a direct link between the government and the group of physicists in America who were immersed in this work.

One might designate Einstein’s letter to the president as the earliest postal history of the bomb except for a few complicating factors: Einstein did not compose the letter, although he signed it. Einstein did not mail the letter to FDR, but to the actual author, physicist Leo Szilard. Szilard personally delivered it to a White House advisor; he did not post it. Perhaps Roosevelt’s Oct. 19 reply that thanked Einstein for sending his advice offers a clearer explicitly postal beginning.

Whether or not collectors count archived letters of famous men as postal history, a punster might truthfully write that the Einstein-Szilard letter set off the chain reaction that led to the creation of the atomic bomb: On Oct. 12 Roosevelt authorized the creation of the Advisory Committee on Uranium chaired by Lyman J. Briggs, director of the Bureau of Standards, which convened on Oct. 21. On Nov. 1, the committee recommended that the government support the physicists by budgeting funds for the purchase of graphite and uranium, and impose a regime of secrecy over the experiments.

Briggs’ committee and a series of others that followed supported atomic energy research by leading physicists at a number of universities from coast to coast. In the summer of 1941, a group at the University of California demonstrated that bombarding uranium with neutrons created two new elements, which they named neptunium and plutonium, and reported that plutonium had the same fission characteristics as the rare U-235 isotope of uranium.

Origin of the Manhattan Project

On June 17, 1942, President Roosevelt approved his advisors’ recommendation to proceed with plans to design and build a nuclear fission bomb. The Army Corps of Engineers was placed in charge of the project, with temporary headquarters in New York City. On Aug. 13 it became known as the Manhattan Engineer District (MED); less formally, the Manhattan Project. At the beginning, Col. James C. Marshall was put in charge. On Sept. 17 Col. Leslie R. Groves was placed in overall command, promoted to the rank of brigadier general six days later. MED headquarters relocated to Washington, D.C.

The 2011 book Atomic Frontier Days by John M. Findlay and Bruce Hevly explained the consequence of the plutonium discovery for the atomic bomb:

Because scientists did not know of a single best method for making the new weapon, and because the United States could not afford to choose the wrong one, Groves committed the Manhattan Project to explore the different methods simultaneously. When scientists told him that either uranium-235 or another substance, plutonium-239, could serve as the fissionable material in an atomic explosion, Groves determined to secure a secret supply of both. In September 1942 he acquired 59,000 acres in Tennessee for the Oak Ridge facility, devoted to isolating enough uranium-235 to fuel atomic weapons. (The fissionable isotope uranium-235 comprises less than 1 percent of naturally occurring uranium, most of which is uranium-238. Most work at Oak Ridge was devoted to isotope separation, that is, distinguishing between the chemically identical U-235 and U-238 atoms based on the tiny differences in their masses.) In November, seeking a site for the laboratory where bombs would be designed and assembled, Groves arranged to purchase a boys’ boarding school at Los Alamos, New Mexico. Then he turned his attention to the matter of manufacturing plutonium-239.

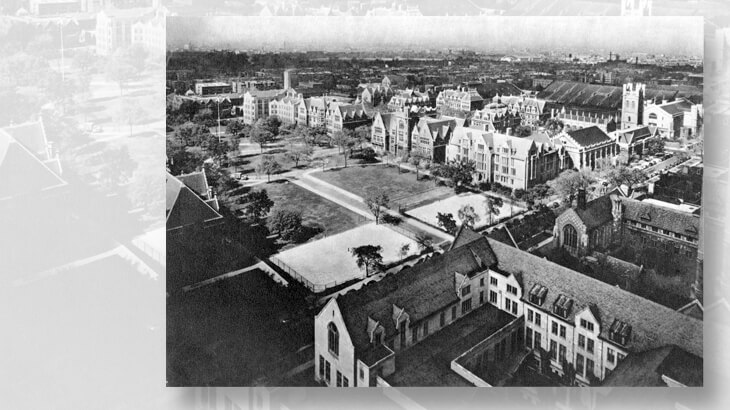

Groves’ initial inclination was to put the needed reactors and processing plants at Oak Ridge. In the middle of deliberations, however, on December 2, 1942, plutonium’s promise was affirmed when scientists led by Enrico Fermi at the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago achieved the world’s first controlled nuclear chain reaction.

The success of the Chicago project, which had been conducted in cramped quarters on a squash court beneath the Stagg Field sports stadium, proved that plutonium could be manufactured from the fission of natural uranium. But the laboratory test yielded only microscopic quantities of the new element, far too trivial to build a bomb. Even the huge Oak Ridge facility was too small and too close to the Knoxville population center to be safe in the event of an accidental explosion or radiation release.

In mid-December Groves decided that the facility for processing uranium into plutonium should be located in a remote part of the Far West. His representative flew over the Columbia River basin in Washington and Oregon, and recommended the area of Washington near Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland as the most suitable site. Groves toured Hanford in person on Jan. 16, 1943, and approved the choice. Eviction of local residents of those towns, about 1,500 people, began in February. Many were given just 48 hours to pack up and leave. The White Bluffs post office closed May 31; no one lived there any longer.

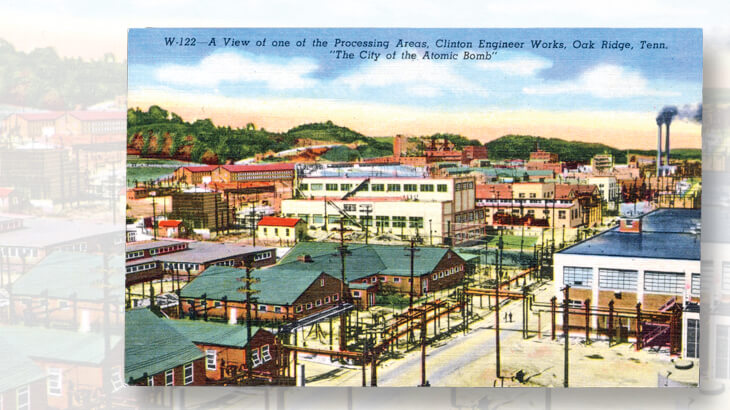

By war’s end, Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) at Oak Ridge, about 25 miles west of Knoxville, occupied about 92 square miles and had a population of 75,000. Hanford Engineer Works (HEW) occupied 670 square miles of south-central Washington, with a population of about 50,000. The Los Alamos laboratory, about 40 miles northwest of Santa Fe, occupied 87 square miles of New Mexico and was home to about 6,000 military people, scientists, and their families. These were the three secret so-called Atomic Cities of World War II. Wartime mail to and from all three locations was subject to censorship.

Site W at Hanford, Washington

In a March 2005 La Posta article “The Manhattan Project & Beyond: Postal Historic Evidence,” Richard W. Helbock summarized the magnitude of the Hanford project:

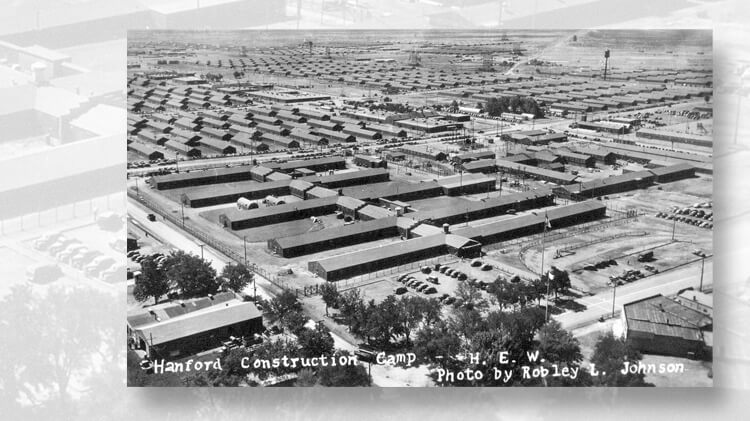

The Hanford Engineer Works roared into life in the early months of 1943. In late March General Groves outlined construction plans for the site that included three huge nuclear reactors spaced miles apart on the right bank of the Columbia River; two chemical separation areas south of the plants; a construction camp at Hanford; a plant for making uranium slugs and testing pile materials on the Richland-Hanford Road; and a town providing residence for operating personnel at Richland.

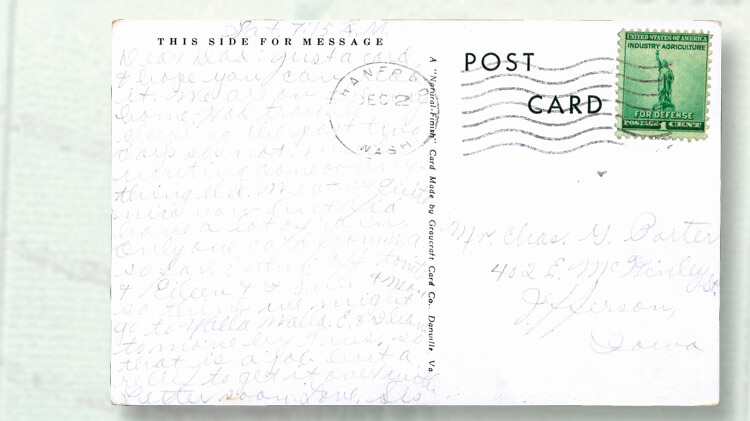

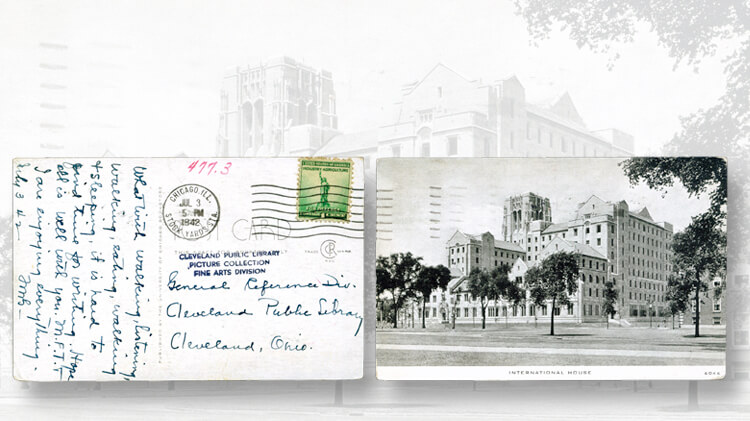

A new Hanford post office opened May 31, 1943, as a branch of Pasco, and was designated Hanford Branch April 30, 1945. Florida collector Paul Filipkowski, who assembled the most comprehensive collection of postal items related to the atomic bomb, had no Hanford cover in his five-frame exhibit titled “The Manhattan Project” at the Napex stamp show in 1988. Helbock illustrated a 1¢ Benjamin Franklin postal card with a Hanford Sept. 16, 1943, philatelic favor cancel and backstamp, but he had no commercial mail to or from Hanford.

The so-called Tri-Cities area of Richland, Pasco, and Kennewick was the nearest and most populous commercial center, with a combined 1940 population of 6,000 before the influx of military and civilian Hanford staff. Pasco and Kennewick were outside the restricted area. Some HEW employees who worked on classified projects lived in off-site quarters rented in those towns.

Part of their reason did not speak well of the men in charge, who flouted President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802 that forbade racial discrimination in defense industries. African Americans and other people of color endured prejudice, segregation, and inequality at every turn. They were confined to the most menial jobs and the lowest pay grades regardless of their qualifications and experience, and lived in the worst available housing.

An article by Annette Cary in the Feb. 27, 2016, Tri-City Herald reported on an exhibit titled “The Atomic Frontier: Black Life at Hanford” at the Northwest African American Museum in Seattle:

Husbands and wives lived in separate dorms. If they wanted to move out, their choices were few. Hanford boasted that it housed its workers in the largest trailer park in the world during WWII. But the trailer lots for black workers were segregated and in less desirable areas of the park.

Kennewick had no black residents even into the 1960s, according to news reports. In Pasco, blacks could live in the rundown eastern section of the city. … Elsewhere in Pasco, “many retail stores and restaurants refused to serve black customers,” according to the exhibit.

According to History of the Hanford Site 1943-1990 by David Harvey, surveillance and censorship extended beyond the personnel employed at HEW to include everyone at Richland:

Although attempts may have been made to make Richland Village appear to be a normal town, the necessity for strict security still played a role in the government town. The Richland Village phone book was stamped as a classified or restricted piece of information. Richland residents’ mail was examined to ensure no sensitive information was being communicated out of town through the mail. Phones were tapped to listen for a breach of security or loose talk. Photographs could not be commercially sold or published without permission of the area manager.

According to the History of Richland, Washington website, “By 1943, Richland had been designated as a ‘closed city,’ a restricted access area that could only be accessed by residents and personnel approved by the US Army. The addresses were misleading and mail was postmarked as originating at Seattle.” Perhaps the same was true for most Hanford mail. A Navy post office at Pasco served a Naval Reserve Air Base located there, not Hanford.

Access to Hanford has continued to be restricted ever since, but the Army opened Richland after the war, with a 1945 population of about 25,000.

Site X at Oak Ridge, Tennessee

The official headquarters of Clinton Engineer Works opened Oct. 26, 1942, at the Andrew Jackson Hotel in Knoxville. Enough land had been purchased to begin construction on Nov. 2. The Clinch River bounded the tract on the west, south and east; the rest of the border was a steep rise called Black Oak Ridge that ran diagonally from southwest to northeast. The first CEW structure, the Administration Building, was completed March 15, 1943, and all entrances were secured April 1 and closed to the general public.

Col. Marshall, the man who had preceded Gen. Groves as chief of the Manhattan Project from June to September 1942, served as the first District Engineer (officer in charge) at the Tennessee location until August 1943. He named the site Oak Ridge in July 1943. The first residents occupied on-site trailers July 13. Retail stores and a guest house opened in early August.

The purpose of the Oak Ridge facility was to enrich uranium, which meant to separate the rare fissionable U-235 isotope from the common U-238 isotope. Physicists had conceived three methods that probably could achieve this, but no one knew whether they would work. Groves resolved to implement all three. Accordingly, the Y-12 plant employed electromagnetic separation; the K-25 plant, gaseous diffusion; and the S-50 plant, liquid thermal diffusion.

A fourth plant designated X-10 was the world’s second nuclear reactor after Fermi’s in Chicago, which processed uranium into plutonium. Its purpose was to develop techniques that would be applied on a much larger scale at Hanford, and to provide plutonium samples for scientific experiments at Los Alamos.

The Oak Ridge post office was established August 16, 1943, with mostly Women’s Army Corps members assigned to monitor mail and local media for breaches of security. A passage from the 2013 book The Girls of Atomic City: The untold story of the women who helped win World War II by Denise Kiernan narrated the story of postal censorship as experienced by a civilian secretary, Cecilia Szapka Klemski, nicknamed Celia:

. … one day, Celia’s mother called with an unexpected request: Stop writing home. This from the woman who never wanted her to be away in the first place.

“I just can’t understand your letters!” her mother complained. “Stop writing them.

“What do you mean, you can’t understand them?” Celia asked when she got her mother on the phone. “Everything’s all blacked out,” Celia’s mother final explained.

“Blacked out?” Celia wondered.

“There are these big, black bars covering all these words in your letters,” her mother continued. “I can’t make any sense out of them!”

Every letter she received, her mother told her, was the same: Words and phrases struck through with black ink, leaving her to try to make sense out of what remained.

At least Celia’s mother’s letters managed to get through.

On occasion, people who tried to write family members living at Site X by addressing letters to “Oak Ridge” got those letters returned to sender with a note reading simply: “There is no such place as Oak Ridge, Tennessee.”

The returned letters probably were replies from families of construction workers. The Sept. 22, 1943, Postal Bulletin notice read, “Oak Ridge … Anderson County, special by Army, from Knoxville, 7 miles southeast of Oliver Springs; 8 miles southwest of Clinton; 25 miles west of Knoxville … (This post office has been in operation since August 16, 1943.)” For five weeks after Oak Ridge was open for business, postmasters and mail clerks elsewhere had no knowledge of its existence.

By the fall of 1943, the town was on its way to becoming the fifth-largest city in Tennessee, but was not found on any map. In May 1945, it reached its overall peak of 82,000 employed in construction, operation, and services. Owing to the war and the draft, women outnumbered men there by a ratio of about 20 to one. As at Hanford, African Americans were segregated, assigned to menial jobs only, and housed in the worst quarters.

The influx of construction workers, scientists, engineers, clerical workers, and military personnel strained the capacity of all services, including mail. The 1950 book The Oak Ridge Story by George O. Robinson Jr. quoted a litany of complaints published in the mimeographed Sept. 25, 1943, Oak Ridge Journal, including, “The post office is too small.” The District Engineer replied, “An officer is in Washington now arranging for the change from fourth to second [class] post office.”

Branch post offices opened at Trailer City, West Oak Ridge, Gamble Valley, Wheat Colony, and Happy Valley, all of them located inside the restricted area. I have never seen a cover posted at any of those offices. The main office became a first-class station on April 1, 1944. A publicity photo released by the Army in August 1945 shows postal patrons in lines at the central Oak Ridge post office during the December 1944 Christmas rush.

In the early days of construction, military personnel assigned to Oak Ridge used the nearby Clinton post office. Helbock pictured a postcard from a military police corporal canceled at Clinton. Construction workers used a post office box at Knoxville assigned to the J.A. Jones Construction Co. Filipkowski showed a postal card from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to “Mr. Lester E. Lebo, Box 1711, V-89, Knoxville, Tenn.” in his exhibit. V-89 was the number of Lebo’s tiny on-site prefabricated dwelling called a hutment.

Both the Helbock and Filipkowski collections included covers canceled at Oak Ridge, one apiece, indicating the difficulty of collecting them. Arizona collector Joseph G. Bock showed two Oak Ridge covers in his Aripex 2015 stamp show program “Development and Delivery of the U.S. Atomic Bomb 1942-1946.” One from an on-site CEW residential address is hand canceled Sept. 22, 1943; the second, from a private in the Army’s Special Engineer Detachment barracks, is machine canceled May 31, 1945.

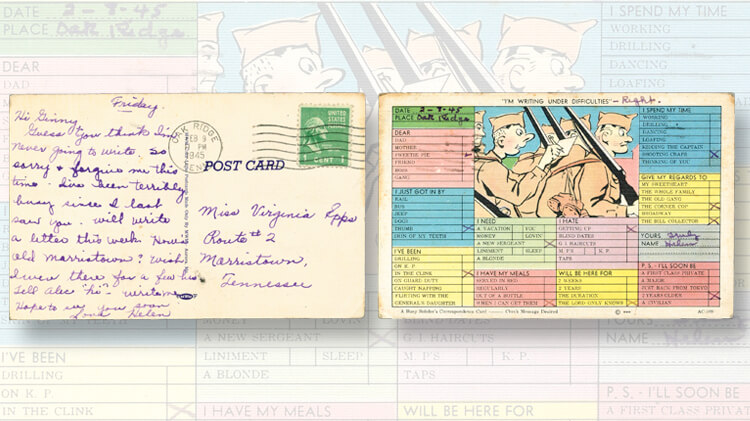

My collection includes the postcard illustrated here, canceled Oak Ridge, Feb. 9, 1945, from a woman named Helen to a friend in Morristown, about 60 miles away. To the printed inscription at the top “I’m Writing Under Difficulties,” she added, “Right.”

The sender’s name at the time was Helen Schultz. She had been recruited while she was a student at Morristown High School. She earned a so-called Q clearance, the highest level of security, and was aware that the purpose of her work operating and performing maintenance on a calutron (a device that used powerful electromagnets to separate the isotopes) at the Y-12 plant was to enrich uranium, though she had no knowledge of the weapon it was meant to arm. She later worked in the X-10 laboratory.

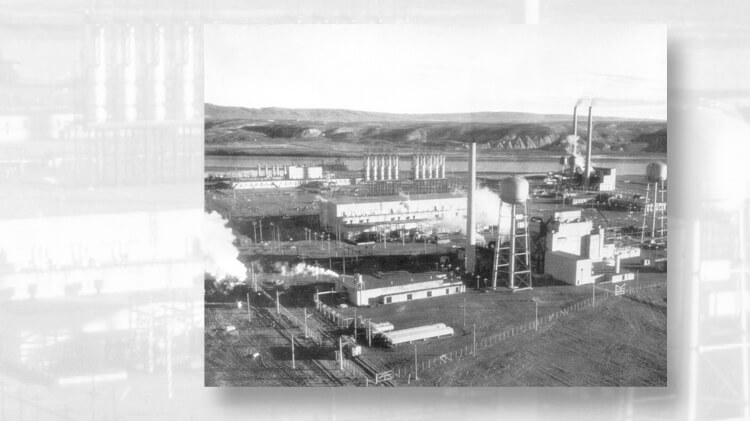

After the war she married Keith Lowery, who had been a construction worker at Oak Ridge. Helen Lucille Schultz Lowery died in September 2014 at age 87. A picture postcard published after the bombing of Hiroshima shows part of the Y-12 complex where she had worked as a young woman.

A remarkable cover appeared on the front page of the December 2009 Tennessee Posts newsletter published by the Tennessee Postal History Society. Addressed to the Chattanooga Public Library and canceled at Oak Ridge Aug. 4, 1945, the recipient inscribed the upper-left corner of the envelope, “Today August 6/45 the world was told of the Atomic Bomb.”

Oak Ridge remained a restricted area until March 19, 1949.

Part 2 of this feature will explore mail to and from the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory where the atomic bombs were designed and constructed, locations where tests and practice runs were conducted, mail related to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and postwar activity of the Manhattan Project.

Remembering Paul Filipkowski

I became acquainted with Paul Filipkowski as a fellow plate-number coil enthusiast in the early 1980s. He was a postal worker who often found newly issued PNCs before dealers obtained supplies of them, so we frequently engaged in trades. Later I learned of his interest in the atomic bomb and other nuclear weapons, not only as a philatelist but also as a historian.

Filipkowski’s interviews with participants in the design, manufacture, and delivery of atomic bombs in World War II preserved first-hand accounts for future generations of researchers.

In 2005, La Posta editor and author Richard W. Helbock wrote that nuclear weaponry “was controversial from its inception and remains so today.” Filipkowski’s legacy embodied every side of the controversy. He was a man with intense, complex, and occasionally ambivalent feelings about the subject. His concerns energized his search to find and interview people who had personally been involved with the bomb, including some of its survivors in Japan.

After historian Gar Alperovitz had declared in a syndicated opinion column that use of the atomic bomb had not been necessary to win the war, Filipkowski replied with a point-by-point rebuttal in a Sept. 29, 1989, letter to the Gainesville Sun. He summed up, “I believe that, as destructive as the bomb was, Truman made the least abhorrent choice available to end the war as humanely as possible. The bomb ended the war.”

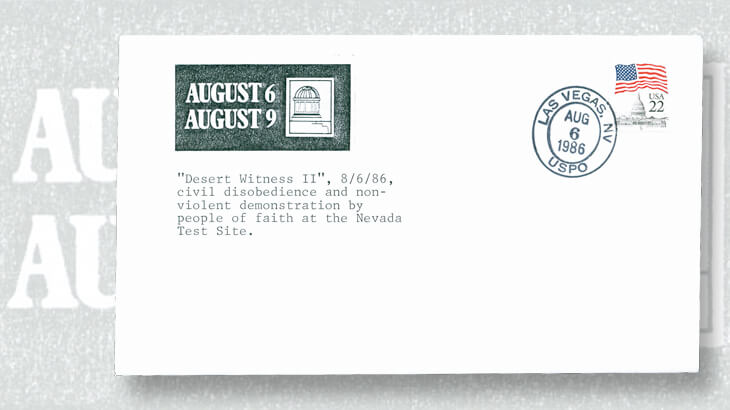

Yet Filipkowski was a religiously motivated pacifist who not only publicly opposed nuclear weapons and tests, he participated in civil-disobedience protests and prayer vigils that trespassed on the Nevada Test Site. The protests had been organized by Quakers and Roman Catholics of the Franciscan Order, and were conducted annually on Aug. 6, the Hiroshima anniversary.

As the first collector to form a competitive exhibit of atomic bomb postal history, Filipkowski gathered hundreds of covers from the men and women who had sent and received them in the 1940s. A majority of the atomic bomb covers in today’s collections came to us through his efforts 30 years ago.

Sadly, Filipkowski died in an automobile accident in 1991, at age 37. We miss him.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers