US Stamps

Treasure trove of U.S. stamp dies lies behind vault at Bureau of Engraving and Printing

By Bill McAllister, Washington Correspondent

One of Washington’s secret stamp treasures lies not at the National Postal Museum nor at the headquarters of the United States Postal Service in L’Enfant Plaza.

Look, instead, inside a huge basement vault at the Bureau of Printing and Engraving.

Ten years after the BEP printed its last postage stamps, it still retains in this vault the original dies as an invaluable legacy of its rich history as one of the world’s premier stamp printers.

A stamp die is the original engraving of a stamp design, usually recess-engraved in reverse on a small flat piece of soft steel.

In traditional intaglio printing, a transfer roll is made from a die, and printing plates are made from impressions of the transfer roll.

The stamps the BEP produced might belong to the Postal Service, but the dies, officials say without qualification, belong to the Bureau.

They are all there on the vault’s second floor, marked by two small red and white plastic signs that say: “post office dies.”

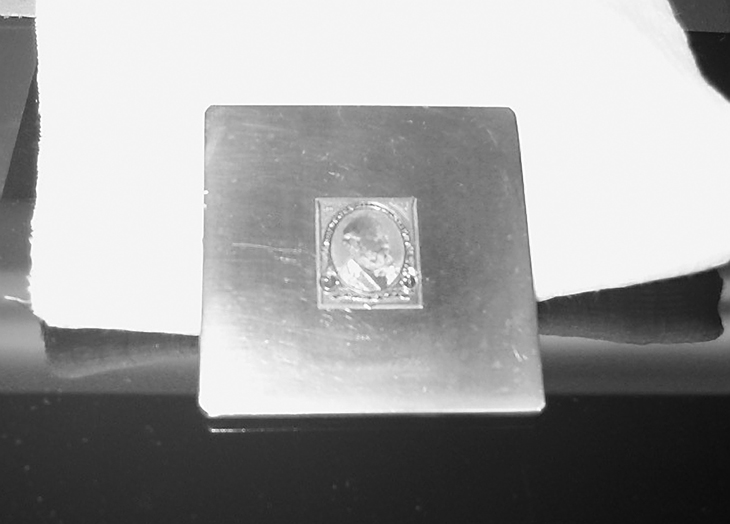

Dating from at least 1916 to the end of BEP stamp printing in 2005, the dies are small steel plates that, for the most part, carry the hand-engraved images of the stamps the Bureau often designed and then printed.

When removed from their dusty shelves and the beeswax covering that prevents them from rusting, the dies can shine with a silvery luster that would rival any mansion’s silverware cabinet.

Rarely seen by the public, the Bureau cannot say for certain how many dies are in the vault.

“We know it’s over 1,000,” said spokeswoman Lydia Washington, explaining the uncertainty over the numbers.

“They are in the process of re-cataloging, so things are a little hectic,” she said.

Long the subject of much collector interest, the dies have remained in the vault, most untouched for years.

They are available for inspection by the one remaining banknote engraver who used to work on stamps for the Bureau, Kenneth Kipperman.

But as Otis Davis, a foreman at the vault who has watched the collection for more than 40 years, acknowledged, the dies are now used less often than they were when stamps were a major part of the Bureau’s production.

Today the dies are pulled out by the engravers only when one of the philatelic souvenir cards the Bureau produces contains a design taken from a BEP stamp.

An exception came when the Postal Service decided to reprint its most famous error — the upside-down airplane on a 1918 24¢ airmail stamp (Scott C3a). According to Roy Betts, a postal spokesman, the new printer “did have access to the original die.”

“The die went to the Postal Museum and proofs were pulled off the original,” he said. “Those proofs were then used to print the new version of the Jenny.”

The $2 Jenny Invert stamp, in a sheet of six, was issued in 2013 to celebrate the 95th anniversary of the original 1918 Jenny Invert.

Mostly, the dies remain shelved in Davis’s huge vault along with dies for currency notes, souvenir sheets and other items that the Bureau has produced.

Getting to see the dies is not easy. It took Linn’s several months to arrange a visit to the vault.

Cameras were not allowed near the vault’s massive 100-year-old, four-foot-wide door that is locked nightly.

Bureau historian Dr. Franklin Noll and lead museum curator Hallie Booker did bring several of the dies out of the vault to share with me.

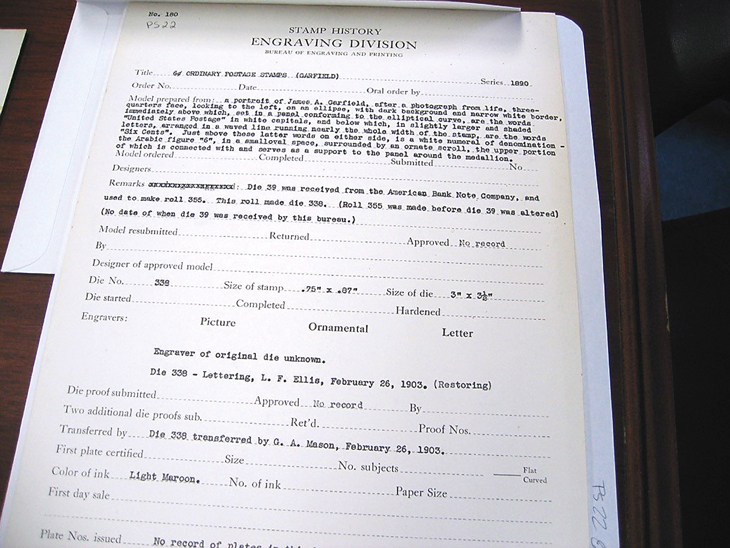

There was the die for the 6¢ James Garfield stamp that the American Bank Note Co. had originally created for its 1890 definitive (regular-issue) series.

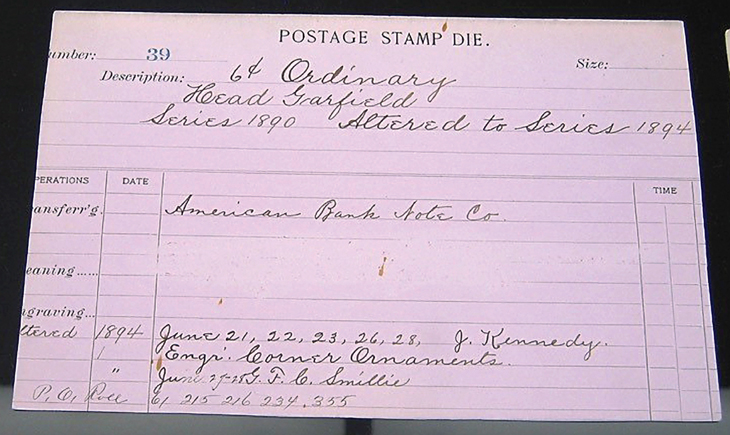

The designs of the 1890 stamps (Scott 219-229) were altered by the Bureau for its inaugural 1894 series by adding triangles to the upper corners of the ABN Co. dies.

If you look carefully, you can see the triangles on the 6¢ Garfield die, pictured here.

On the BEP “Postage Stamp Die” card shown here, the 6¢ Garfield die is described as “6¢ Ordinary/Head Garfield/Series 1890 Altered to Series 1894.”

According to the BEP, approximately 3,900 die cards are in its possession. Included are “cards for some of the early dies produced by American Bank Note Co. and other security printers,” said BEP spokeswoman Lydia Washington.

“According to our curator, some of the non-BEP, pre-1894 dies may have been transferred to the BEP by the United States Postal Service when BEP was awarded the contract to produce postage stamps. The dies date from 1874 through 1998.

“For the vast majority of dies in the BEP’s collection, there is a die card containing some description of related information pertaining to that die which may include the title, name of the Engraver or Designer, production runs, project objective, etc.”

Also illustrated nearby is the BEP “Stamp History” summary for the 6¢ Garfield, the first stamp the BEP printed in its 1894 series.

Collectors refer to the 1894 stamps as the First Bureau Issue (Scott 246-263).

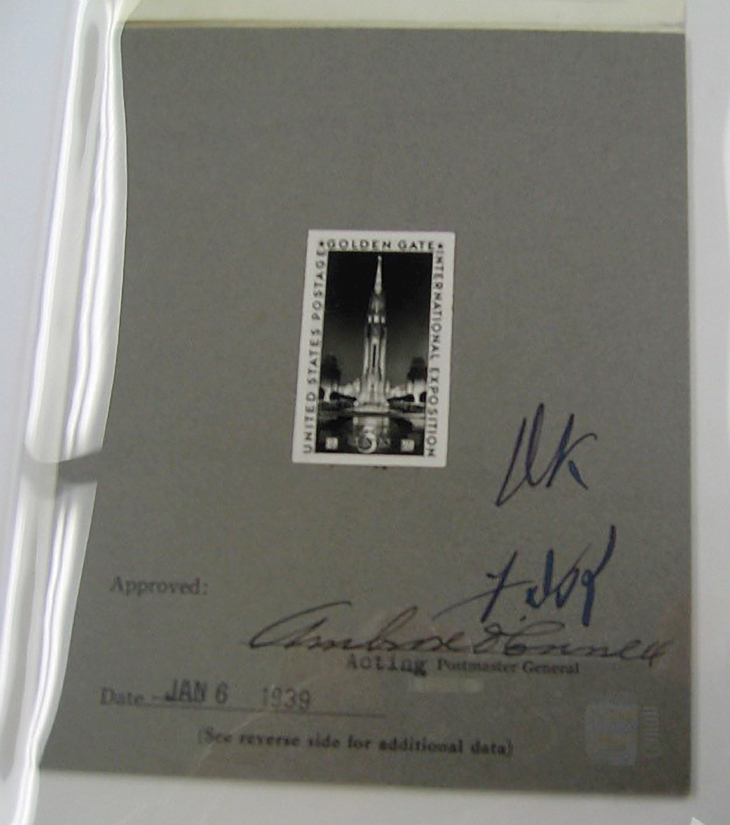

The most fascinating items that I saw were not stamp dies, but three proposed designs for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition commemorative issued on San Francisco’s Treasure Island (Scott 852).

What made the small gray folders holding the designs so interesting were the comments stamp-collecting President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote on them in pencil.

He feared the “3” in the denomination inscription was too big on the first design shown him by Postmaster General James Farley on Dec. 21, 1938.

The Bureau went to work immediately and came up with a second design, which the president also rejected.

FDR found the third design acceptable and wrote “OK” and his initials in black ink on the folder. As shown on the folder, this third design was approved Jan. 6, 1939.

Because the stamp was issued on the opening day of the exposition, Feb. 18, 1939, the Bureau probably created a rush order to print and ship sheets of the stamp across the country in time for the first-day ceremony.

FDR’s penchant for offering rough sketches for stamp designs is well-known.

Less known perhaps is his critical eye on elements within a design, which these design folders illustrate.

The folders and the accompanying technical papers, which outline the pedigree of each stamp the Bureau produced, are not kept in the vault.

Nonetheless, they are invaluable resources that the BEP still shares with collectors who write with questions about the stamps.

The technical sheets on the 1918 24¢ Curtiss Jenny airmail stamp (Scott C3) make no mention of the infamous printing error that made that stamp a world-renowned classic.

For most of the Bureau’s life, the stamp dies have created little attention.

However, in 1987 after a tiny Star of David was discovered on the $1 Bernard Revel stamp (Scott 2193), the BEP ordered a search of its dies for any other secret marks that might have been added to a design.

No other such marks were found, and Kenneth Kipperman, the BEP engraver who placed the star in the beard of Revel, the longtime president of Yeshiva University, was returned to his duties as an engraver.

Today he still has all the tools of an engraver at his desk, and he said the Bureau has all the equipment it would need to resume stamp engraving.

Some of Kipperman’s tools are illustrated nearby. At the top of the picture are so-called “Die Work” cards for four stamps that Kipperman engraved (left to right): 29¢ George Meany (Scott 2848), 5¢ Canoe coil (2453), 33¢ Empire State Building from the 1930s Celebrate the Century set (3185b), and 45¢ French Revolution Bicentennial (C120).

Postal Service officials have said the Bureau’s stamps, which often were produced from engraved intaglio dies, became too expensive, and that the Postal Service found private printers could produce lithographed stamps at a much lower cost.

The BEP does issue an occasional stamp with intaglio features, but postal officials have expressed no interest in returning to government-produced postage stamps.

And what about the stamp dies?

“They are permanently here,” said a BEP official.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers