US Stamps

U.S. mail across the Atlantic by land-based aircraft: Part 2, 1942-46

By Ken Lawrence

Part 1 of this report ended with the inauguration of trans-Atlantic air transport service via Ascension Island, midway between South America and West Africa, by the United States Army Air Transport Command (ATC).

Looking back after the war was over, The Army Air Forces in World War II edited by Wesley Frank Craven and James D. Cate rendered this judgment: “Probably no other air base used by the Air Transport Command had such strategic importance as that on Ascension Island.”

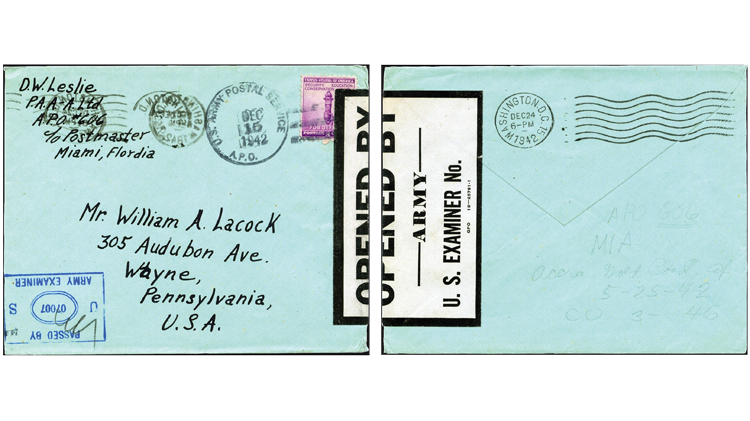

When transport flights first began to use the mid-ocean island base as a fueling stop in July 1942, trans-Africa air and ground services were operated by Pan American Airways-Africa Ltd. (PAA-Africa), ATC’s principal contractor, but that arrangement was only temporary.

Militarization of PAA-Africa

Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, chief of the Army Air Forces, had issued an order in February 1942 to militarize PAA-Africa, but ATC lacked sufficient resources to take over those airfields until later in the year. Pan Am executives resisted militarization to the bitter end, but unsuccessfully. The transition finally occurred between October and December.

Jim Hester told me the story of how his late father, George Hester, was coerced to enlist. (The son inherited his father’s passion for collecting.) PAA-Africa had appointed George Hester senior air traffic manager at Accra, Gold Coast:

“My dad, along with a number of the other key managers at Pan Am Africa, was given the choice of accepting a second lieutenant commission immediately there in Accra and getting his paycheck from the Army Air Corps under their direct command, or being put on the next available flight back to the U.S. and having to report immediately to his local recruiting station to be inducted into the infantry as a buck private.”

Connect with Linn's Stamp News:

Hester offered to sign on instead as a first lieutenant, and the Army accepted his offer. He was inducted on Oct. 2, 1942. A short time later, he was ordered to Maiduguri, Nigeria, as squadron commander at that air base. While he was there, legendary war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote a report datelined “SOMEWHERE IN AFRICA” that told how GIs at that remote outpost were “completely divorced from life as they knew it back home.”

[This trip] takes you into parts of deepest Africa that few Americans had ever seen before the war. It makes you realize more than ever how completely global, poking into the farthest and tiniest recesses, this war really is.

Nearly everywhere you go you find some American troops, from mere handfuls up to thousands. They are not fighting troops; they are the builders and maintainers of airdromes, who sort of catch our multitudes of airplanes and toss them on to the next station on their long haul from America to Russia, India, China. …

At the most weirdly isolated places they get mail from home quicker than we do in North America. …

The commanding officer at this place is Lt. George Hester of Tubac, Ariz. He spent five years with American Airlines in the States and with Pan American Airways in Central America before coming over here. He likes his work and finds the life interesting and full.

According to The Army Air Forces in World War II,

The forced withdrawal of the Pan American organization from Africa did not affect its contract services in the Western Hemisphere or its flying-boat, and later C-54 and C-87, operations across the South Atlantic to the western coast of Africa. It even operated transports across Africa to the Middle East and India, as did other contractors, but after December 1942 all planes crossing Africa used bases and facilities completely under military control. …

By the end of 1942 the fleet operating on the transatlantic jump had been increased to twenty-six planes—nine C-54’s, four C-87’s, four B-24D’s, five Stratoliners, and four Clippers.

The Cannonball Express

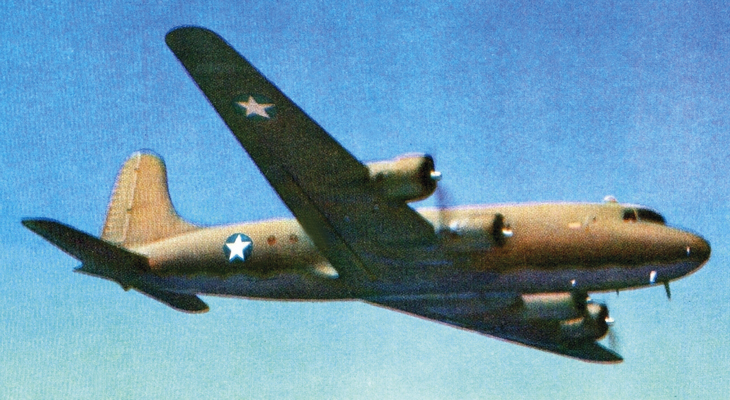

Douglas Aircraft Co. delivered the first C-54 (Air Corps designation for the land-based four-engine DC-4 Skymaster long-range transport airplane) in July 1942. An Air Force historian called this plane “the workhorse where long range and a heavy load were important considerations.”

In August 1942, ATC assigned two C-54s to Pan Am for South Atlantic service. As the transition to militarization of PAA-Africa was nearly complete, ATC contracted with Pan Am to operate B-24s and C-54s on a shuttle service from Miami to Karachi under the carrier’s newly created Africa-Orient Division.

The first group of Africa-Orient transports departed Miami on Nov. 10, 13, 14, and 15 for a rendezvous at Natal, Brazil. On Nov. 16 they took off from Natal at 15-minute intervals, fully loaded with passengers, cargo and mail, for Ascension Island en route to Accra, their first fueling stop on the African continent.

By the time those four-engine transports took to the air over the Atlantic, Pan Am’s contract route to India had been dubbed the Cannonball Express run. The existence of Cannonball was a military secret until mid-March of 1944, when the veil of censorship was lifted so the press could publish the story. The March 13 New York Daily News reported:

Seven days round trip from the U.S. to Northern India. … That’s the new Cannonball Express record rung up by Pan American Airways operating under contract for the Air Transport Command. The Cannonball has crossed the Atlantic 2,200 times and has logged more than 14,500,000 miles of flying for the Army since November 1942.

Pan Am’s own magazine, New Horizons, called it the “fastest express service in aviation history.”

When the company’s publicity department later tried to reconstruct the origin of the name, staff members gave contradictory accounts (which might all be true). Here are two versions copied from the Africa-Orient Division file in the Pan Am archives at the University of Miami Richter Library:

In the first, Jim Howley, an operations division representative at Miami, upon learning that the first aircraft was soon to depart on a new schedule farther than previously flown, remarked, “Oh, this one’s going through on the long-haul like a Cannonball!”

In the second, a Mr. Simmons in the operations division at Natal, “needing some designation to distinguish the Karachi service and its crews from the regular shuttle operations,” dubbed the former “Cannonball Crews.”

Whichever actually occurred first, the name stuck.

An unpublished ATC history told a more nuanced version of the Cannonball inauguration than Pan Am’s new releases:

While all correspondence during the fall of 1942 in connection with this route lists Cairo or Karachi as the terminal points, it was not until February of 1943 that the C-54’s actually got beyond Accra on a regular schedule.

But by February, Cannonball had 60 crews flying 15 airplanes in round-the-clock relays, which from then on comprised a majority of Pan Am’s South Atlantic shuttles. That increased capacity benefited ATC performance over the entire route.

An ATC document titled “Résumé of Transportation Operations for the week ending February 6, 1943” showed a combined total of 22,316 pounds of mail carried over the South Atlantic route by a fleet of 41 aircraft, 37 of which were landplanes, and a backlog of 19,292 pounds awaiting transport. It showed 6,791 pounds carried over trans-Africa and Middle East routes, with a backlog of 5,227 pounds, carried by a fleet of 56 landplanes.

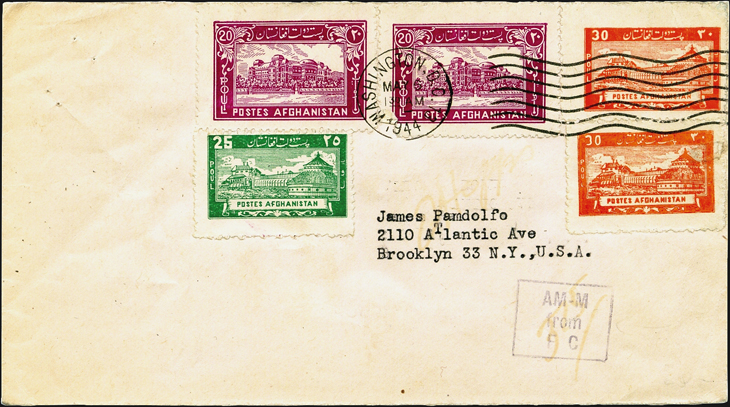

The Cannonball route eventually extended to Calcutta, making a direct connection to ATC flights over the Hump to China, many of which were operated by China National Airways Corp., a Pan Am subsidiary under contract to ATC.

In September 1944, the Cannonball route shifted. Instead of crossing the South Atlantic via Ascension Island and then across Central Africa, the new route went from Miami via Bermuda and the Azores to Casablanca, Morocco, and onward across North Africa to India. By that time, Pan Am’s Africa-Orient Division was flying more ton-miles per day than all of Pan Am’s other divisions and subsidiaries combined.

Despite that huge volume over some of the world’s most daunting and inhospitable areas, the Africa-Orient Division boasted the best safety record of all of ATC’s wartime contractors, with only two planes lost involving passengers and crews, according to an unpublished history in the Richter Library file.

Trans-Atlantic Airmail Service after Militarization

After militarization, the Air Transport Command alone was responsible for all trans-Atlantic civilian, military and Official mail to and from Africa and Asia.

In a Nov. 27, 1942, memorandum, Maj. M. J. Deutsch, postal officer of the ATC’s Africa-Middle East Wing (AMEW) wrote:

AMEW is carrying mail for all or nearly all allied Governments in the world either directly or through transfer to and from connecting carriers. Civil mails are given excellent service with little or no delay at any point in AMEW.

According to the unpublished Official History of the South Atlantic Division, Air Transport Command:

A picture of the status of transportation operations across the South Atlantic … may be obtained from the following figures [for the week before December 26, 1942]: Four-engine aircraft assigned for transport operations: 4 B-24D’s; 9 C-54’s, 4 C-98’s, 5 C-75’s, 4 C-87’s. … Mail movement (pounds) Natal-Africa 2,737, Africa-Natal 307 Total 3,044 Total for all ATC overseas routes 24,681. …Similar figures for the Natal-Miami run were as follows: Two-engine aircraft assigned for transport operations: 24 C-47’s and C-53’s (3 additional planes were assigned, but were not available for use at this time). … Mail movement (pounds) 15,285. Mail backlog (pounds) 745. …

These figures show that there were three cargo aircraft crossing the South Atlantic in each direction daily and approximately four moving in each direction on the Miami-Natal run. About 60 per cent of the Natal-Africa and Africa-Natal traffic was passengers, 30 per cent cargo and ten per cent mail. On the Miami-Natal route, 61 per cent was cargo, 34 per cent passengers, and five per cent mail. …

Half of the mail flown by the ATC overseas also passed through Natal.

On May 13, 1943, Major Deutsch ordered larger mail quotas for every trans-Africa flight, and underlined the point for emphasis:

200 pounds and 500 pounds of mail will be given first priority on each 2 engine and each 4 engine plane respectively, leaving from Accra on every scheduled flight or special mission flight, and mail in excess of this allotment will be carried on space available basis if priority is established. It is further indicated that it is the duty and responsibility of the Air Transportation Officer at each station to see that the movement of mail is expedited. . . . [G]ood mail service can never be attained unless the minimum allotted priority is granted on each plane every day.

Actual loads exceeded those minimums. During the first 20 days of May 1943, “an average of 415 pounds of mail on all two-engine aircraft and 600 pounds on all four-engine aircraft” had been carried from Accra.

After the last Boeing B-314 (C-98) Clipper flying boats were transferred to the Navy in May and June 1943, nothing remained of the prewar commercial airmail apparatus on those routes. Almost all airmail between North America, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and the Far East was now transported by land-based aircraft regardless of whether it was military, diplomatic, or civilian. (Formally, the Civil Aeronautics Board authorized Pan Am’s FAM 18 flying boat winter route flights to collect mail at Bolama, Portuguese Guinea; and Fisherman’s Lake, Liberia; in practice Pan Am frequently omitted those stops because of the trivial amounts of mail involved.)

The Fireball Express

Until the fall of 1943, contract carriers, chiefly Pan Am, transported about 95 percent of the mail between Miami and West Africa. The Army Air Forces in World War II explained:

Only a few military crews had been trained for four-engine aircraft because, up to this point [June 1943], nearly all the C-54’s and C-87’s assigned to the command were operated by the contract carriers, which were responsible for their own operational crew training.

To remedy that imbalance, ATC established a training unit at Homestead, Fla., exclusively as “a four-engine school specializing in C-54 instruction but also giving operational training to a number of C-87 and B-14 crews. In November 1943 the Ferrying Division opened the ‘Fireball’ run from Florida to India in which C-87’s and later C-54’s were employed.”

Col. William H. Tunner had been given command of ATC’s India-China Division, including the Hump route over the Himalaya Mountains that connected those countries, in December 1942. On June 30, 1943, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general.

The Fireball Express, a route parallel to Pan Am’s Cannonball Express run that had begun a year earlier, connected to the Hump route in India. It more than tripled the capacity of the 15,000-mile flyway between America and the Far East, expediting airmail along with passengers and cargo.

In his memoir Over the Hump, Tunner wrote:

It’s easy to think of the Hump as just one route; actually, of course, it was many air routes, separated both laterally and vertically, from thirteen bases in India to six in China. At first we had a narrow corridor of only fifty miles to accommodate two-way traffic. … On toward the end we had a corridor two hundred miles wide. … Through this corridor, every day, were flying an average of 650 planes, one taking off every two and a quarter minutes of the day’s twenty-four hours. …

This was all new. No other air operation, civilian or military, had ever before even attempted to keep its fleet in continuous operation all around the clock, in all seasons, and in all weathers. No other operation had such extremes of weather and altitudes. And our cargo was varied, to say the least — from V-mail to mules to machinery. The age of air transportation was born right there on the Hump.

At the time of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the entire Army Air Corps had possessed just 11 four-engine transport planes. When Japan surrendered, ATC had more than 200 C-54s flying the Hump route alone. The Army Air Forces in World War II summed up the significance of these achievements:

Most important in the long run, no doubt, the Air Transport Command’s crowded airways to China were the proving ground, if not the birthplace, of mass strategic airlift. … The India-China experience made it possible to conceive the Berlin airlift of 1948-49 and to operate it successfully.

Reopening the North Atlantic Air Transport Service

Meanwhile, after clearing the South Atlantic mail backlog in the summer of 1942, Lt. Col. Lawrence G. Fritz, a former barnstormer, airmail pilot, and TWA vice president, had taken charge of ATC’s stalled North Atlantic transport operations. He began by performing a characteristic daredevil stunt.

The Dec. 4, 1944, issue of Time magazine reported:

One day in the fall of 1942 he stepped into a B-24, flew it out into the North Atlantic seeking the worst weather “front” he could find. His plane picked up a load of ice, lost flying speed and dropped into a spin. Fritz, a veteran airline pilot, straightened her out just a few hundred feet from the water. He came back still convinced that he was right. He was handed the job of proving his point as C.O. [commanding officer] of the North Atlantic Division.

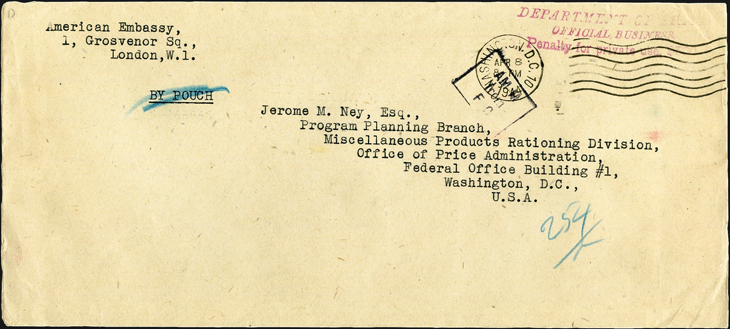

ATC’s North Atlantic route had reopened on April 13, 1942, with its eastern terminal relocated from Ayr to Prestwick, Scotland. The service operated an average of three round trips per day, and was never again suspended until after the close of hostilities. The primary purpose of that route was to transport urgent military and diplomatic personnel and communications between Washington and London.

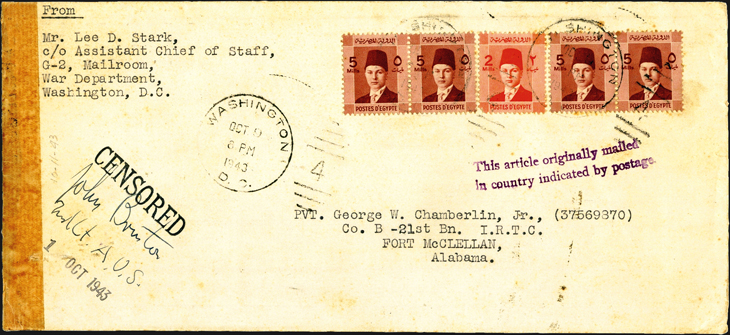

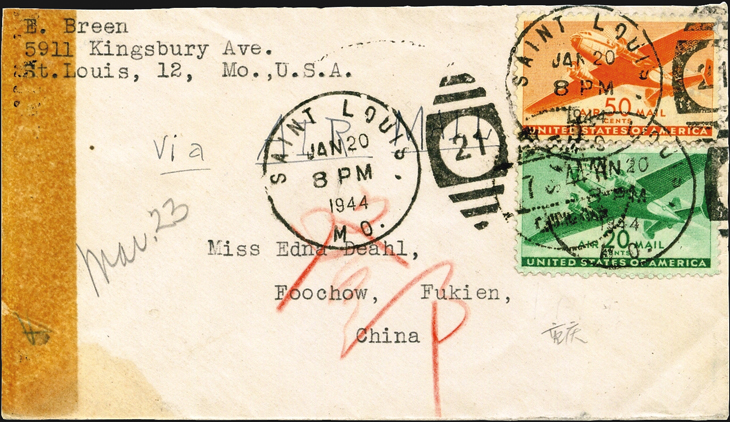

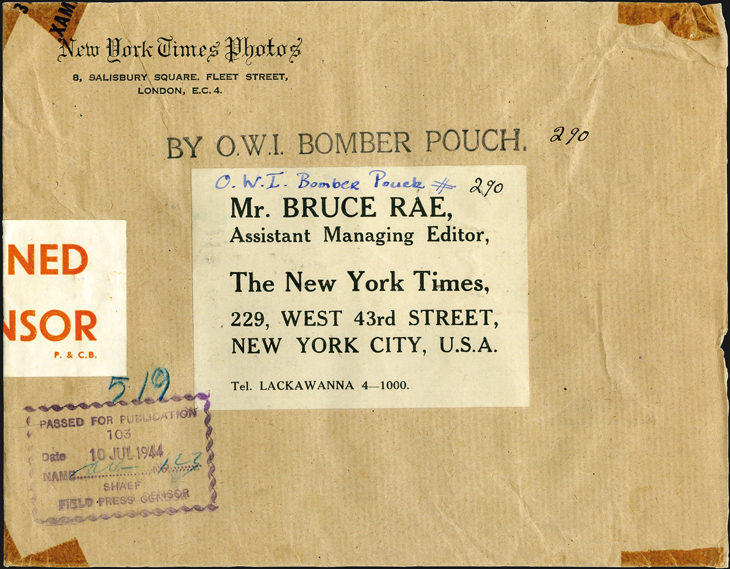

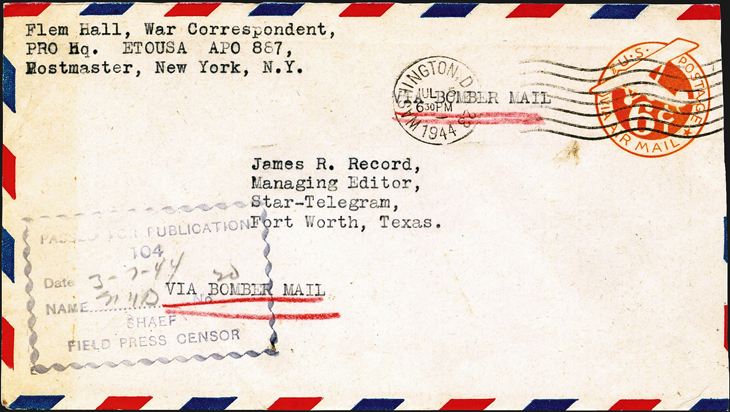

The most urgent letters and parcels were endorsed “bomber pouch” and “bomber mail,” because the Consolidated B-24 Liberators that began these services had been built to be long-range bombers, but had been stripped of their armaments and converted to transports for the sake of increased speed and range. As can be seen in covers from my collection, frequent users of these services were war correspondents and photographers sending dispatches to their papers.

Trans-Atlantic bomber mail was a free service of the Office of War Information, but airmail postage had to be added at the 6¢ per half-ounce military concessionary rate to secure onward air transport within the United States.

Additional Trans-Atlantic Landplane Routes and Extensions

In January 1943, after Allied forces had liberated Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, a Transcontinental & Western Air service that flew C-54 Skymasters was established from Washington via the South Atlantic to Accra, then north to Marrakesh, Morocco, for two weekly shuttle flights between Marrakesh and Prestwick in Scotland before returning to Washington. The frequency of the TWA flights doubled in February.

In July 1943, after Axis forces had been driven out of Africa, the Marrakesh route was extended to Cairo and Karachi, laying the groundwork for a faster trans-Africa service than had been possible over the Central Africa crossings.

In March 1944, the Marrakesh-Prestwick C-54 shuttle was replaced by a C-87 shuttle service with St. Mawgan, Cornwall, replacing Prestwick as the northern terminus and with Casablanca replacing Marrakesh as the Morocco call, then onward from Casablanca via Algiers, Algeria, to Naples, Italy.

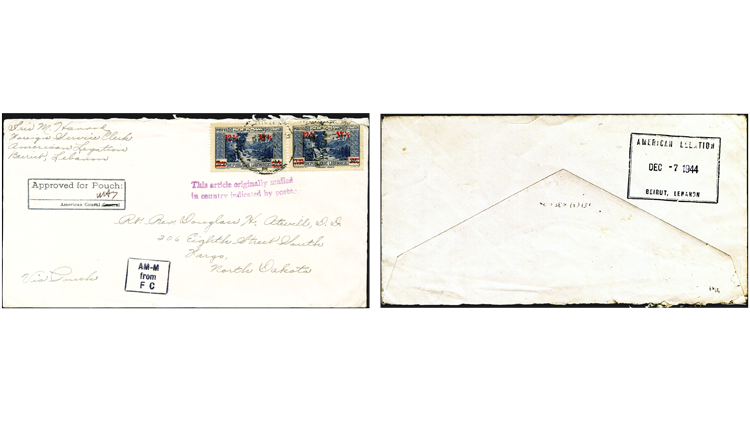

Early in 1944, a secret ATC route was established between Cairo and Adana, Turkey, via Beirut, Lebanon, when Turkey was still officially a neutral nonbelligerent country. Ground crews were disguised as civilian employees of the “American Transport Company.” Another ATC extension ran from Tehran, Iran, to Poltava, Ukraine.

Also in 1944, ATC opened two additional trans-Atlantic C-54 routes, called Crescent and Snowball, over the Middle and North Atlantic, respectively, operated by military crews.

Crescent, which originated at Wilmington, Del., represented a new route to India via the Azores, after the Portuguese government lifted restrictions that had earlier banned military flights from landing there, and across North Africa.

In a passage that failed to credit Pan Am for procedures pioneered on the Cannonball run, Tunner wrote in his Over the Hump memoir:

On the Crescent run, incidentally, I’d set up a pony-express type of operation, with fresh crews taking over at specific points. The plane itself went straight through, from America to its final destination, without the delaying transfer of passengers and cargo.

Mail carried on these flights ought to be indistinguishable from mail carried on Cannonball or Fireball flights, unless a mishap en route caused an identifying mark to be added.

Snowball, begun in July 1944, provided another route between the United States and Great Britain after the successful D-day landings in Normandy.

The Army Air Forces in World War II explained:

The establishment of this new service reflected the obvious need for an increased airlift to the United Kingdom, the availability of additional numbers of C-54 aircraft, and the existence within the Ferrying Division of a reservoir of crews experienced in four-engine operation. The original routing of the flights was from Presque Isle [Maine] through Stephenville in Newfoundland to Valley in Wales and back through Meeks Field in Iceland to Stephenville and Presque Isle.

On Aug. 31, 1944, four days after German forces retreated from Paris, the first ATC flight landed at Orly Field, the Paris airport. On Oct. 4, ATC began scheduled service between France and the United States that averaged three round trips per day.

From Trans-Atlantic Origins, A Global Air Transport Operation

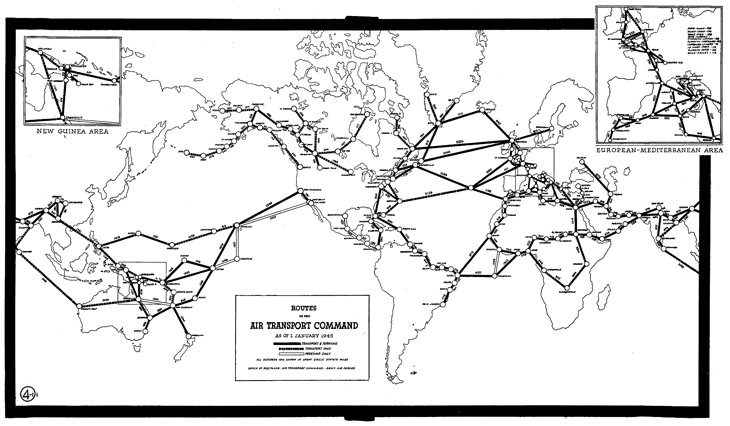

By the end of 1944, ATC routes served every continent, as shown here on the formerly classified January 1945 route map.

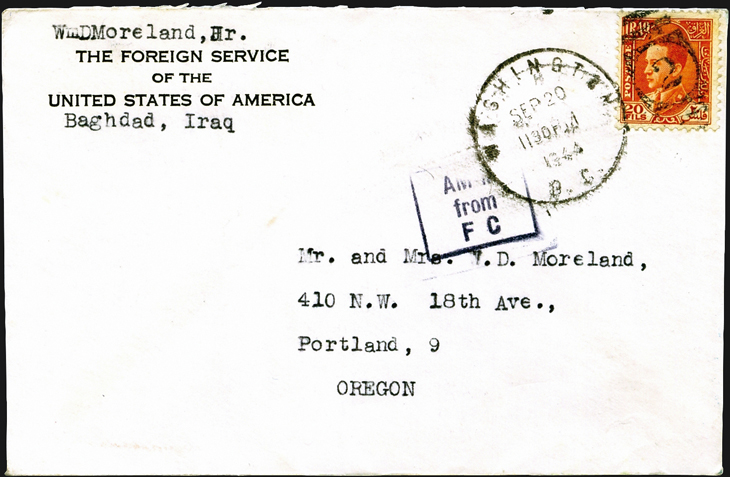

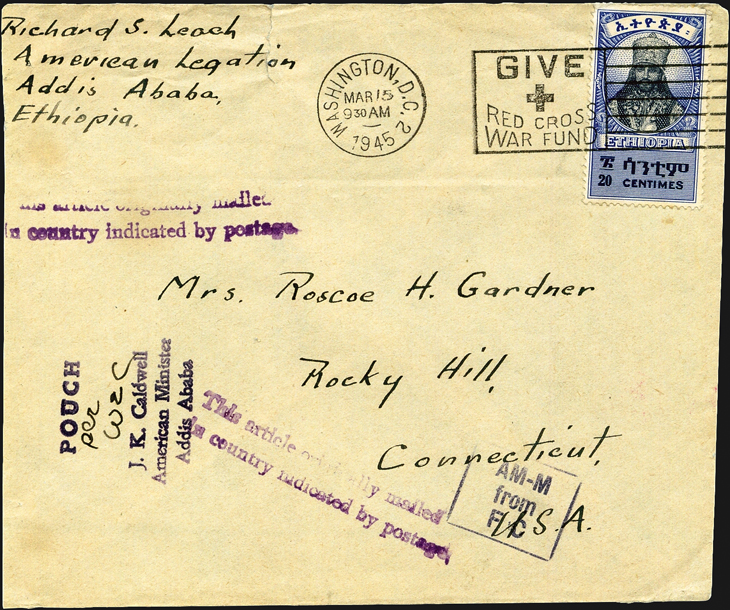

I have illustrated several of my covers that were carried over these routes, which were not served by surface or Navy alternative means.

North Atlantic airmail was the great exception in every respect. Throughout the war, most mail went by surface ship between New York and Great Britain regardless of senders’ instructions and postage prepaid.

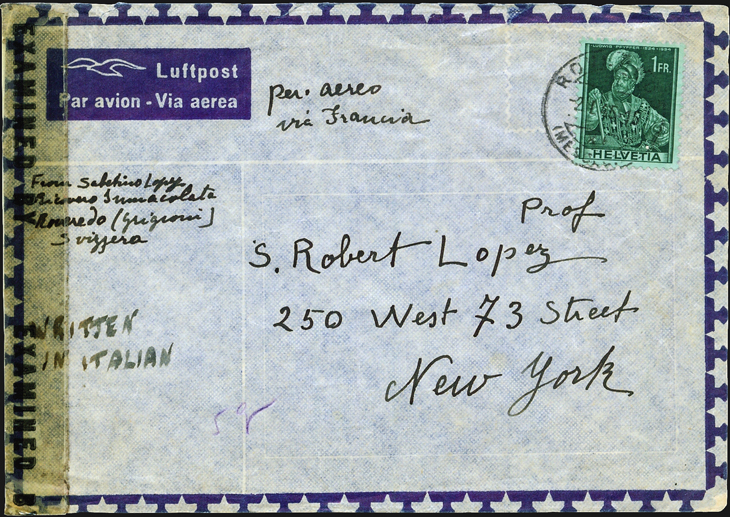

Except for mail of the highest priority, such as bomber/bomber-pouch and urgent military airmail, it isn’t possible to prove that a letter went by air unless it has verifiable departure and arrival dates as evidence. Even then, the means of transport varied: Pan Am’s “Y” route, documented by David Crotty, flew Consolidated PB2Y-3 Coronado flying boats across the Atlantic for the Navy.

After the cancellation of Navy contracts in late 1944, Pan Am restored commercial Clipper service between New York and Lisbon. American Export Airlines (AmEx) flew Vought-Sikorsky VS-44 Flying Aces seaplanes over its FAM 24 route, also between New York and Lisbon but with less frequent intermediate calls. Canada also operated a North Atlantic air transport service.

Nevertheless, some covers invite analysis that suggest a higher probability of one choice than the others, such as the illustrated Jan. 2, 1945, cover from Switzerland to New York.

Trans-Atlantic Airmail After the Japanese Surrender

By the time World War II came to an end, the Air Transport Command had built the largest airmail service in history, with the Naval Air Transport Service (NATS) in second place. NATS had begun to dismantle its trans-Atlantic services and to restore them to commercial operation in late 1944, but the Army continued to retain and expand routes under its jurisdiction even as it canceled contracts with Pan Am and other private carriers.

Failing to foresee the opposition his plan would evoke in the halls of Congress, Gen. Harold L. George made a bold attempt to extend the ATC’s authority over commercial air transport, including airmail, into the postwar period.

He announced that ATC would demonstrate its capability and potential with an enthusiastically promoted round-the-world demonstration flight scheduled to depart Washington on Sept. 28, 1945. The flight went forward as planned, but the uproar of opposition quickly put a halt to his scheme for the future.

At the time of the Japanese surrender in September 1945, the Cannonball Express employed 175 Pan Am flight crews. The Hump route was officially closed at the end of November, but later transports from China flew over the Himalayas to India as special missions.

When Pan Am restored service between New York and Leopoldville via Gander Newfoundland; Shannon, Ireland; Lisbon; Dakar, Senegal; and Monrovia, Liberia, in January 1946, the route was served by a DC-4 Skymaster until April, when Pan Am acquired new Lockheed Constellation land-based aircraft.

Pan Am’s South Atlantic service from Liberia to Brazil ended May 27, 1946. Cannonball service continued until June 25, 1946, the date when the last C-54 flight returned from the Far East. That was also when Miami ceased to serve as the airmail gateway to Africa and Asia.

The restoration of fully commercial foreign airmail service consolidated all trans-Atlantic operations at New York City.

Never again did Pan Am enjoy the monopoly control of foreign airmail services that had been its exclusive dominion before the war. TWA parlayed its wartime contract services into new commercial routes that provided robust competition, even after Pan Am took over American Airlines services that had been built by AmEx.

For postal history collectors who specialize in trans-Atlantic airmail, July 1946 marked the end of an era. As if to underscore that dividing line, the Post Office Department issued the first new edition of the Official Postal Guide, Part II: International Mail since July 1941.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers