US Stamps

National Bank Note’s proofs testing patents to prevent reuse

One of the legacies of the National Bank Note Co., holder of the United States postage stamp production contract during the 1860s and early 1870s, is the vast number of essays that have survived that pertain to preventing the reuse of postage stamps.

While National Bank Note held Charles Steele’s patent for grilling stamps, the firm pursued the rights of any patent that it believed might be able to compete with the grill.

Sometime between mid-1866 and 1869, National Bank Note either acquired or leased the rights to three very similar patents and put these technologies to the test.

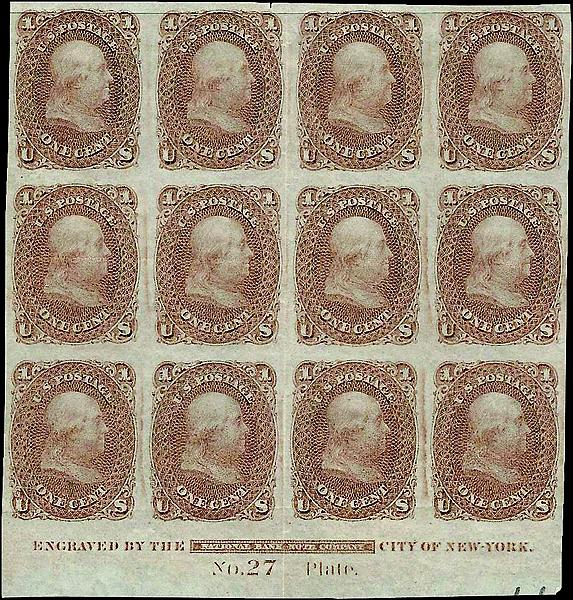

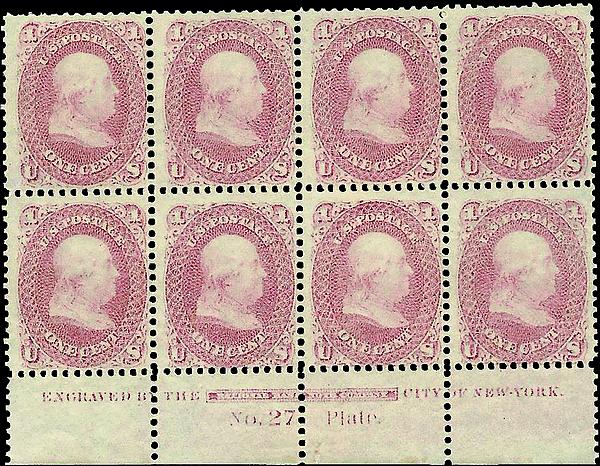

Using stamp production plate No. 27, which featured the image of the 1¢ Franklin design from the then-current 1861 stamp issue, the company conducted printing experiments.

Sheets of 200 were produced in 22 colors. Based on the surviving examples, no more than three sheets were produced in any one color. About half of the sheets were gummed and perforated.

Since a production plate utilizing an accepted design was used, these are considered trial color plate proofs by the editors of the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers.

The three patents used in these experiments are patent No. 53,723 granted to William C. Wyckoff on April 3, 1866; No. 42,207 granted to Henry Lowenberg of New York City on April 5, 1863; and No. 52,869 granted to James MacDonough on Feb. 27, 1866.

MacDonough was president of the National Bank Note Co.

The Wyckoff patent

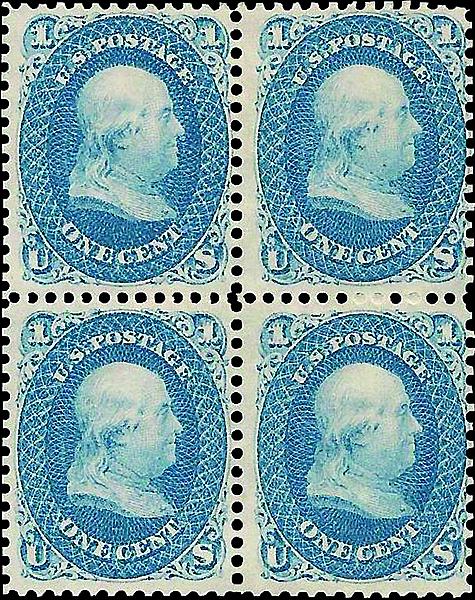

The Wyckoff patent called for coating the stamp paper with zinc oxide. This would form a barrier between the paper and the ink received during the printing process. Wyckoff’s concept produced a very sharp image for the finished product.

To this day, one can use a wet camel hair brush to remove the design from the paper.

The perforated block of eight in rose with original gum pictured here (Scott 63TC6) shows the sharp detail of the complex design of the 1¢ stamp.

The impression is so good that the perforated blue example is often confused and sometimes even offered as the issued stamp. However, a strong light will reveal the barrier coating that is not present on a postage stamp.

The Lowenberg patent

Lowenberg’s idea was very similar to the one developed by Wyckoff. His barrier coating consisted of a water-soluble solution of starch. Any attempt to wash a cancel off one of his stamps would result in both the design and cancel washing away.

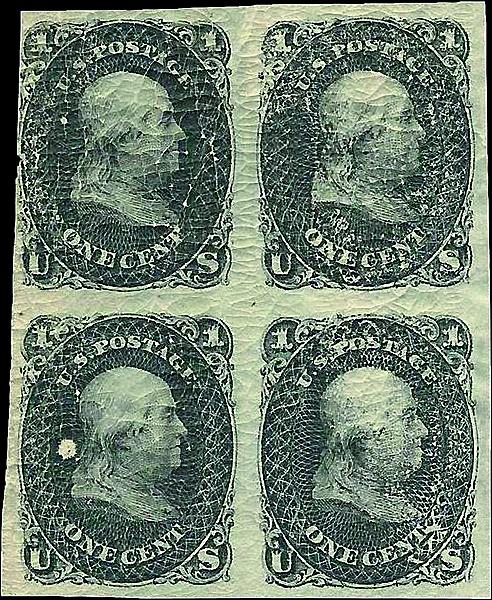

The coating he employed was rather thick and hard to apply evenly. This resulted in a printed image that was not as sharp as the one produced by the Wyckoff patent.

The effects of heat and humidity on the starch coating can be seen on the example in black pictured here (Scott 63TC5). It tends to shrink, crack and wrinkle the paper. From the back, it looks like crocodile skin.

The MacDonough patent

MacDonough’s patent called for printing the stamps with a glycerin-based ink that would prove highly soluble in water. Once again, any attempt to wash the stamp to remove the cancel would result not only in the disappearance of the cancel, but the stamp design as well.

The example shown here (Scott 63TC5) is printed in the only color known to be used to produce this patent. It is a muddy brown, and the details of the stamp design are not very sharp.

•

While all three of these patents showed promise to some degree, none of them made the cut. The National Bank Note Co. did go to considerable expense to test each of them; however, it was the firm’s grilling process that continued to prevail with the U.S. Post Office Department.

If you would like a listing of the known colors for each of the patents, please e-mail me at the address below, and I will send you a PDF file.

My next column will continue to explore some of the different essays created for the prevention of reuse of postage stamps, specifically Henry Lowenberg’s decalcomanias.

James E. Lee has been a full-time professional philatelist for more than 25 years specializing in United States essays and proofs, postal history and fancy cancels. He may be reached via e-mail at jim@jameslee.com, or through his website at www.jameslee.com.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers