World Stamps

Identifying Brazil’s Bull’s Eyes corresponding plates can be fun

By Sergio Sismondo

If you overhear someone saying “Brazil came in second,” you might surmise that the subject of conversation is a soccer championship, or coffee production. Instead, you might learn that Brazil was the second nation in the world to have issued postage stamps, and the first on the American continent to have done so.

Great Britain was the first. The 1-penny black and 2-penny blue were issued May 6, 1840. The Canton of Zurich was next, with their distinctive Numerals of March 1843.

The Empire of Brazil issued stamps Aug. 1, 1843. At first the three issued stamps were used in Rio de Janeiro. That might have been considered a trial period. After 30 days, the stamps were distributed to all major post offices in the empire.

As was the case in Great Britain in 1840, the issuance of stamps in Brazil for prepayment of postage was part of a comprehensive postal reform, touching all aspects of the post office’s business.

On Nov. 29, 1842, two bills were passed that, among other matters, specified that postage fees were to be paid in advance. It was in conjunction with that regulation that postage stamps were considered indispensable. Thus, their preparation was promptly ordered from government printers.

It happened that Johann Jakob Sturz, consul of Brazil in various European capitals, became aware of enormous and continuing economic benefits generated by postal reform in Great Britain. The more he looked into the matter, the more enthusiastic he became in support of such reforms. He wrote to his contacts and friends back home, urging adoption of the British system for handling mail and for payment of postage.

Evidently he was a man of substantial influence: The wheels for a full review of the imperial postal system were promptly set in motion. Reduction of basic postage rates had been the bedrock of the British reform. Uniformity was another. Neither fact escaped the attention of Brazilian authorities.

Before the advent of reform, postage fees were calculated by weight and distance. Single weight was defined as two-eighths of 1 ounce and was applied to maritime transits. A single unit of distance was defined as 15 leagues (approximately 75 kilometers), and was applied for overland mail. Each unit paid 20 reis.

Because Brazil is a very large country, letters between cities typically required 100r to 200r or more for their land postage. There was an additional complication — much of the mail traveled via a combination of means: partly by water, and partly by land. Postage fees for both modes were calculated and summed.

The reform did away with distance-based fees. All letters by land required 60r for the first four-eighths ounce and 30r for each additional two-eighths ounce. All letters by sea required 120r for the first four-eighths ounce and 60r for each additional two-eighths ounce.

These new rates represented a significant saving for the average letter, and ever more so for printed matter, business and legal documents that, according to the same decrees of 1842, paid one half of the standard new postage rates.

Without going into details of currency exchanges, these rates were roughly the same as the fees in Great Britain after their reform, which also were based on one-half ounce weight units.

During the next 10 to 15 years, most European countries reduced their base weight unit to one-half ounce, rendering most rates comparable. Because the new rates in Brazil were based on units of 30r, denominations required for postage stamps were 30r, 60r and 90r. Nothing could have been simpler.

Much has been said about the design of these stamps. Apparently it was intended that the effigy of the emperor would dominate the design, as the monarch dominated British stamps. All the court’s men, the emperor included, had thought so.

However, the director of the National Printing Office expressed some doubts. He sent a memorandum to the minister of the post, stating that in his view canceling the stamps over the portrait of the sovereign might be considered disrespectful. The minister, taking a cautious approach, agreed, and the project took an abrupt turn.

In the new design, the numeral took center stage. There was no indication of country of origin, currency or purpose of the stamp. It was estimated that all such information was not required because foreign mail was not included in the scheme of things.

In subsequent communications, government printers made the point that the lathework would constitute a strong feature against forgery, because according to what was written, government printers owned the only turning machine for making a die in the whole country at the time.

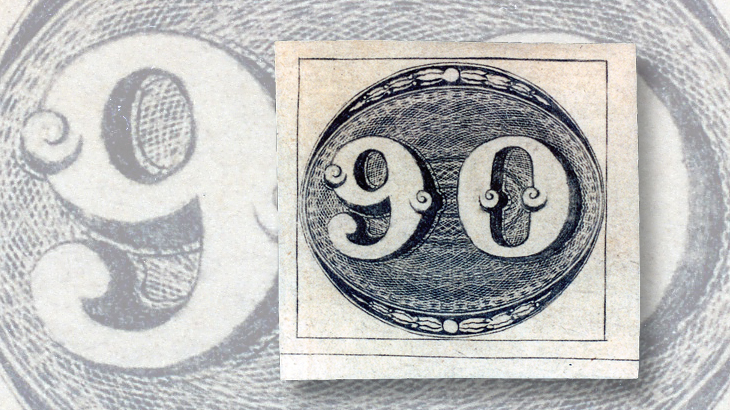

Thus emerged this unusual design, which the people of Brazil themselves gave the nickname “Bull’s Eyes.” In my opinion, it is an elegant design worthy of a great land and a self-assured people. The first illustration above shows a beautiful example of a mint 90r stamp (Scott 3).

All Bull’s Eyes were printed in Rio de Janeiro by government printers. A total of six printing plates were made. The first two are known as the “composite plates.”

Plate 1 has 54 stamp images, divided into blocks of 18 stamps of each denomination, each block with a frame all around, and also showing a horizontal line of separation between the 30r and 60r blocks and between the 60r and 90r blocks.

Plate 2 also has 54 stamp images, but the horizontal dividing lines between the blocks are missing.

At this point, it became apparent that the demand for 90r stamps was lower than the demand for the two lower denominations. It became necessary to print more 30r and 60r denominations.

Plate 3 has 54 stamp images, all of them of the 30r denomination, divided into three blocks of 18 stamps, separated by a small gutter, and unified by two continuous vertical lines at the edges.

Plate 4 has 60 stamp images, all of 30r, arranged in 10 rows of six stamps each. All around there is a single frameline 2 millimeters from the stamps.

Plate 5 has 60 stamp images, all of 60r, with the same arrangement as plate 4, but with the sheet frameline 2.75 mm from the stamps.

Plate 6 has 60 stamps of 60r, with the same arrangement as plate 4, with the sheet frameline separated from the stamps by 2 mm.

Although reconstructions, some complete and some partial, exist for the six plates, realistically only stamps with broad margins, showing sheet framelines or group separation lines, can be easily attributed to one or another plate. Identifying the corresponding plates can be a fun pastime.

In addition to these settings, which remain constant throughout the printings, there are retouches of the plates. These are complicated, and we can deal with them in another column. The same can be said for the different papers that exist.

Also complicated is the matter of what constitutes “early,” “intermediate,” and “late” impressions. Through the process of printing, printers themselves sent messages to their ministers warning that plates were becoming worn, and more plates were needed. Therefore, plate wear is definitely a factor we have to consider. However, it is also true that the degree of inking has much to do with the deep (black) or light (grayish) appearance of the stamps.

Interestingly, the three varieties listed in the catalogs exist from all six plates. With patience and study, it is possible to make quite an array of states of wear and depth of impression for each of the three denominations.

Another aspect that can be rewarding is studying the postmarks on Bull’s Eyes. About 210 different town cancellations are recorded on Bull’s Eyes. Only three of them are common: CORREIO GERAL DA CORTE (Rio de Janeiro); CIDADE DE NICTHEROY; and PERNAMBUCO (in a fancy shield).

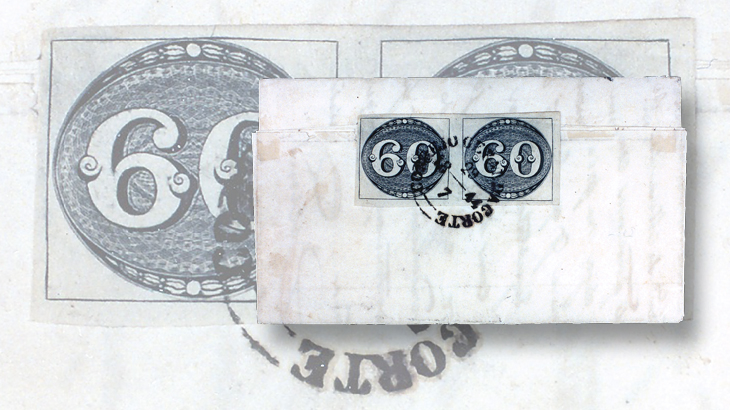

The standard postmark of Rio de Janeiro is shown nearby, on a pair of 60r stamps from an early impression, on a lovely cover dated July 29, 1844.

All the other town cancels range from seldom seen, to rare to very rare. Many in the list are unique. Town postmarks also exist in various colors. Those recorded are: red, yellow, green and blue, all being rare to very rare. The third stamp shown here is a 60r from an early impression with part of a fine red postmark from VASSOURAS in a fancy, decorated rectangular frame.

If you find a Bull’s Eye postmarked Aug. 1, 1843, the first day of issue, you can sound the bell. You have won a philatelic lottery, or should I say “you have hit the bull’s-eye.” Other early dates also command hefty premiums.

In another installment of this column, we will write about classification of the stamps by paper types, by degree of plate wear and depth of color, and about stamp multiples, covers, retouches and re-entries.

Finally, a warning: forgeries of the basic stamps are common, and forged cancellations on manipulated stamps are often seen. Certificates of authenticity are recommended.

All images are from the philatelic archive of Liane and Sergio Sismondo.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers