World Stamps

Britain’s Imperial Airways and BOAC trans-Atlantic airmail of 1937-40

Among the treats for collectors who attended the Aerophilately 2014 international stamp exhibition at Bellefonte, Pa., last September was the unveiling of the American Air Mail Catalogue, seventh edition, Volume 1, by the American Air Mail Society (AAMS). The book consists of three large sections: “Official Contract Air Mail Flights: CAM Routes 1-34,” “Philippine Flights 1911-1946” and “Foreign Flag Flights.”

The first two are revisions of earlier editions, significantly enhanced by illustrations in full color. The third is entirely new and long overdue. Until now, collectors and dealers have had only one comprehensive reference for worldwide inaugural flight covers — the French language Catalogue des Aerogrammes du Monde Entier by Frank Muller, published in 1950, which has no illustrations and only a bare minimum of information on each flight.

The entire AAMS catalog merits praise, but the new section will serve to illuminate my subject here — trans-Atlantic services to and from the United States inaugurated by the British carrier Imperial Airways in the 1930s. As a new subject, “Foreign Flag Flights” is a work in progress, so future revisions may eventually benefit from information I have gathered here.

Airmail to and from Bermuda

In 1930, the American carrier Pan American Airways formed a joint development corporation with Imperial Airways to explore the possibility of inaugurating service to and from Bermuda, intending for Bermuda to be an ice-free fueling stop for flying boats crossing the Atlantic between the United States and Europe.

After a series of frustrating delays, successful survey flights in May and early June 1937 won official approval.

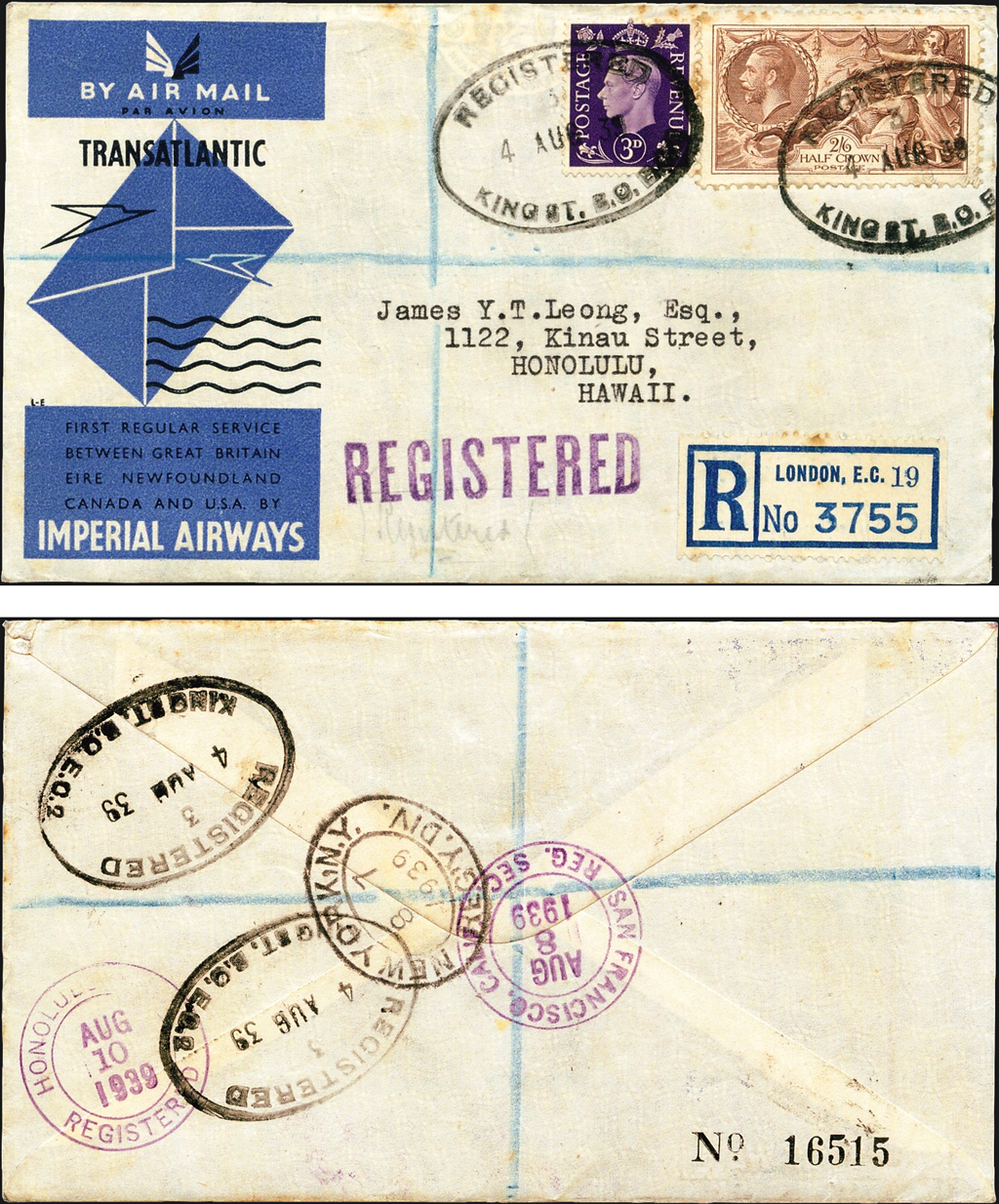

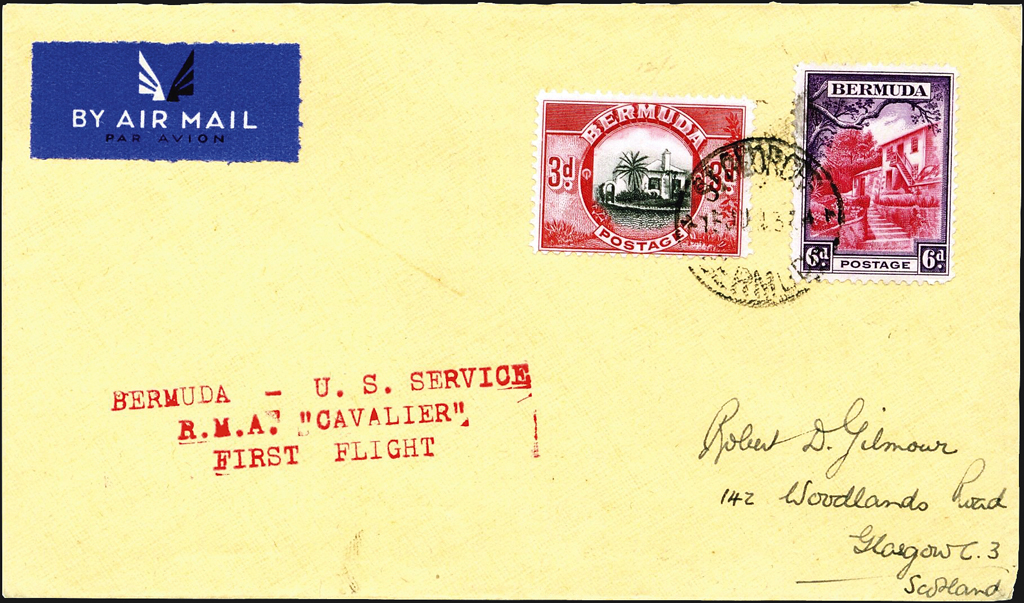

The first Imperial Airways commercial flight on June 16, 1937, by the Short S-23 flying boat Cavalier, carried 38 pounds of mail from Hamilton, Bermuda, to New York City. Souvenir covers from that flight are struck with a cachet in red ink that reads “BERMUDA – U.S. SERVICE R.M.A. ‘CAVALIER’ FIRST FLIGHT.” I believe “R.M.A.” meant Royal Mail airplane or aircraft.

The catalog informs users, “No mail was carried on the return flight from New York, as this leg of the mail service had been assigned to Pan American Airways, as provided in the bilateral agreement between the United States and Bermuda.”

United States and Bermuda authorities had not yet agreed on the terms of Pan Am’s contract.

On Nov. 17, the North American terminus was relocated to Baltimore, to avoid icy winter conditions farther north. The catalog reports, “One hundred covers were carried unofficially by Pan American from Baltimore to Bermuda, then re-franked and flown officially from Hamilton to Baltimore.”

Finally on March 16, 1938, Pan Am was authorized to begin its reciprocal flights on a commercial basis, which inaugurated Foreign Air Mail 17 service between Baltimore and Bermuda until April 6, when the route returned to New York. Souvenir U.S. covers exist for both of those FAM inaugural dates, which are listed in earlier editions of the AAMS catalog.

During a Jan. 21, 1939, flight from New York to Bermuda, Cavalier lost power, forcing the pilot to ditch the aircraft in heavy seas. Ten survivors were rescued, but three died when the flying boat sank. Pan Am became the exclusive carrier on the Bermuda route by default.

Airmail to and from England

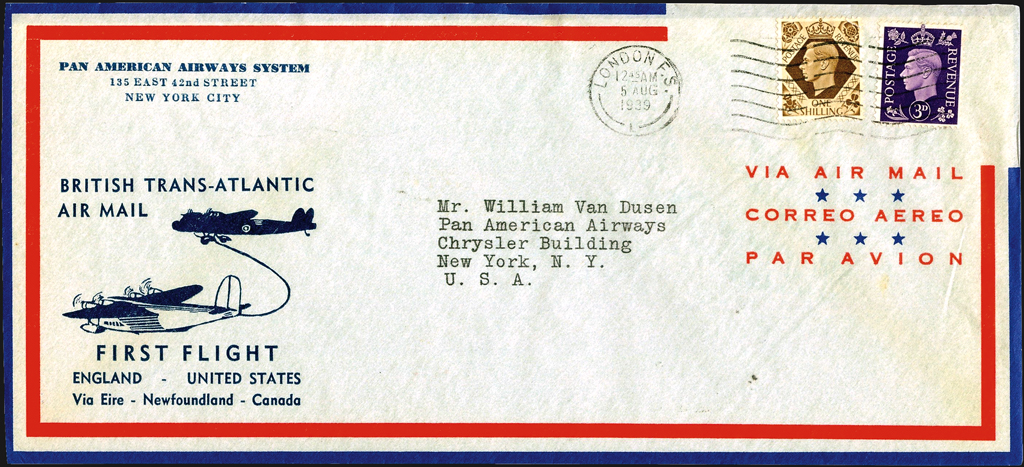

Loss of the Cavalier forced delays in the next phase of Imperial Airways’ trans-Atlantic program, so Pan Am gained the initiative. In May 1939, Pan Am inaugurated FAM 18 service between New York and Marseilles, France, with intermediate calls at the Azores and at Lisbon, Portugal. In June, a northern FAM 18 route added service from New York to Southampton, England, with intermediate calls at Botwood, Newfoundland, and Foynes, Ireland.

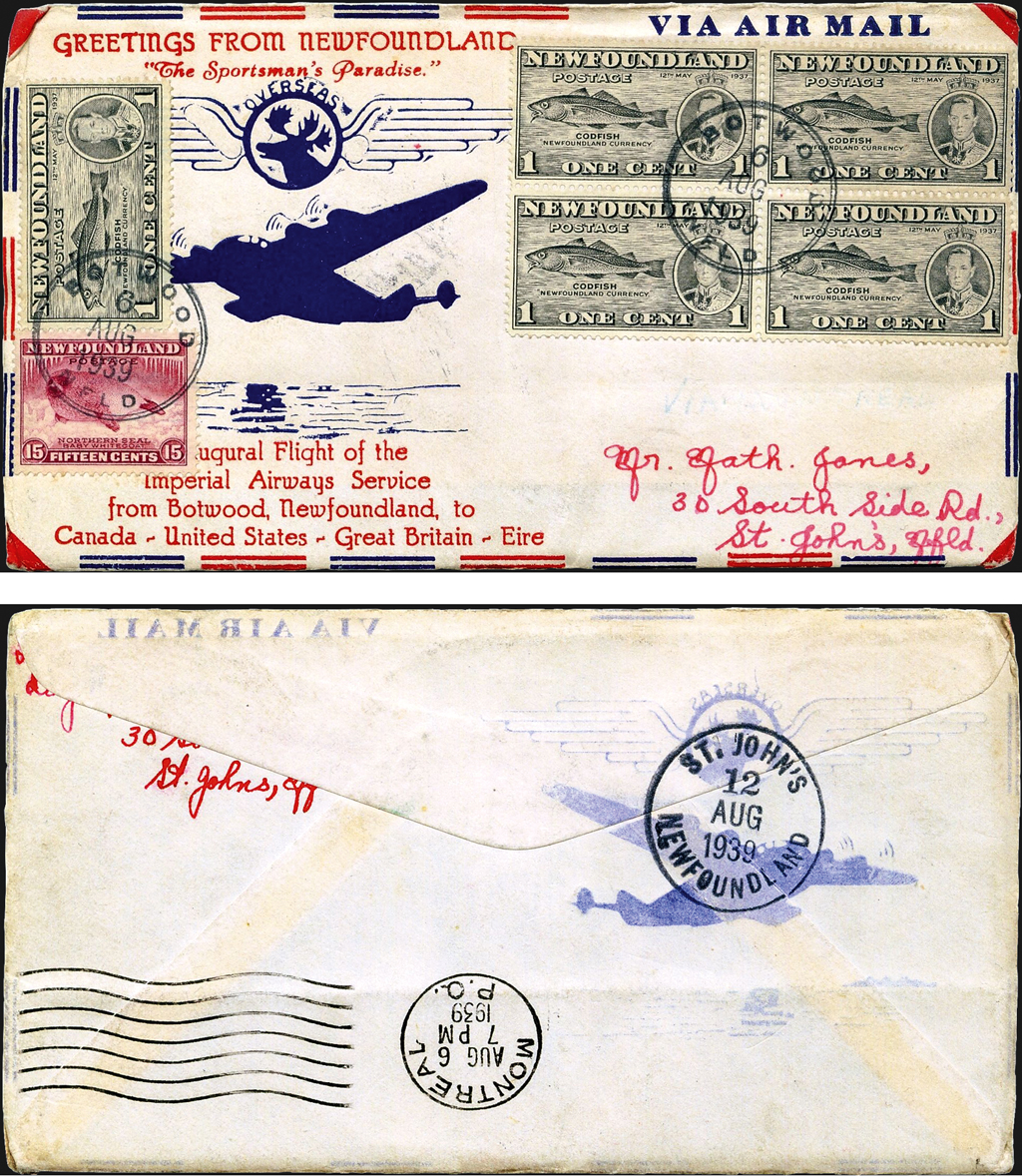

Finally in August, Imperial Airways began its service from England to New York via Foynes, Botwood, and Montreal, Canada. The catalog lists seven collectible covers for these origins and destinations: Southampton-New York, Foynes-New York, Botwood-New York, Montreal-New York, New York-Southampton, New York-Botwood and New York-Foynes.

The westbound flight departed Southampton Aug. 5, arrived at Foynes and Botwood the same day, arrived in Montreal and New York Aug. 6. The eastbound flight departed New York Aug. 9, arrived in Montreal the same day, arrived at Botwood and Foynes Aug. 10 and in Southampton Aug. 11.

The July 28 Postal Bulletin announced the new British service and advised that “No philatelic handling will be given at New York of mails dispatched by the first flight,” but the Aug. 2 issue reported that “upon request therefor by the Postal Administrations of Canada and Ireland, the air mails received by first flight from those countries will be backstamped at the New York post office.”

Imperial Airways listings in the AAMS catalog end with this note: “Imperial Airways, Ltd. and British Airways were combined on April 1, 1940 to form British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC),” but no BOAC flights earlier than July 1946 are reported in the catalog. Even among the Imperial Airways flight segments, collecting opportunities are more abundant than the bare-bones listings in the catalog suggest.

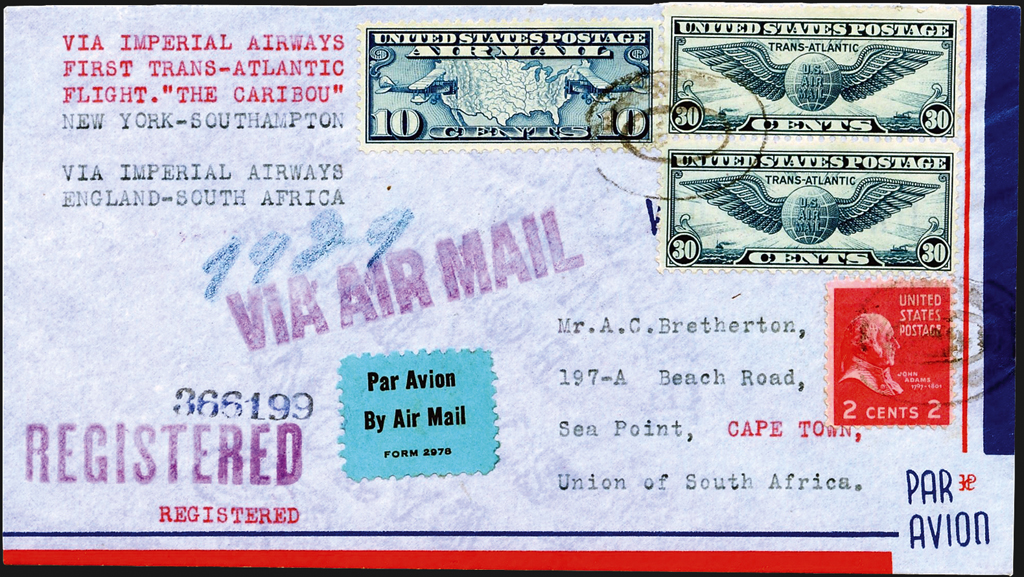

Contemporaneous reports called attention to additional choices. The October-November 1939 issue of Aero Field observed: “Covers despatched from U.S.A. to South Africa and Australia are particularly interesting for these were the first to be flown over an all-air Empire route to destination. They reached Cape Town and Sydney on August 18th and 24th respectively. Considering the obvious desirability of these items, surprisingly few have been reported.”

British airmail specialist Harold D. Phillips, who used the name A. Phillips in his philatelic ventures, published Air Mail Magazine from 1939 until his untimely death at age 50 in 1944. At first, his magazine was devoted entirely to the subject of first flight covers, which he bought and sold, but in 1941 he added Airgraphs (microfilmed letters similar to American military World War II V-Mail) as a sideline.

Among the Imperial Airways souvenirs Phillips offered his customers were round-the-world covers on official cacheted envelopes, franked with stamps of the United States, Great Britain and Hong Kong, postmarked Aug. 9 New York, Aug. 12 London, Aug. 30 Hong Kong, and Sept. 12 Brooklyn. Those were in addition to his basic set of 17 cacheted covers that included each combination of origin and destination.

Imperial Airways Service in 1939

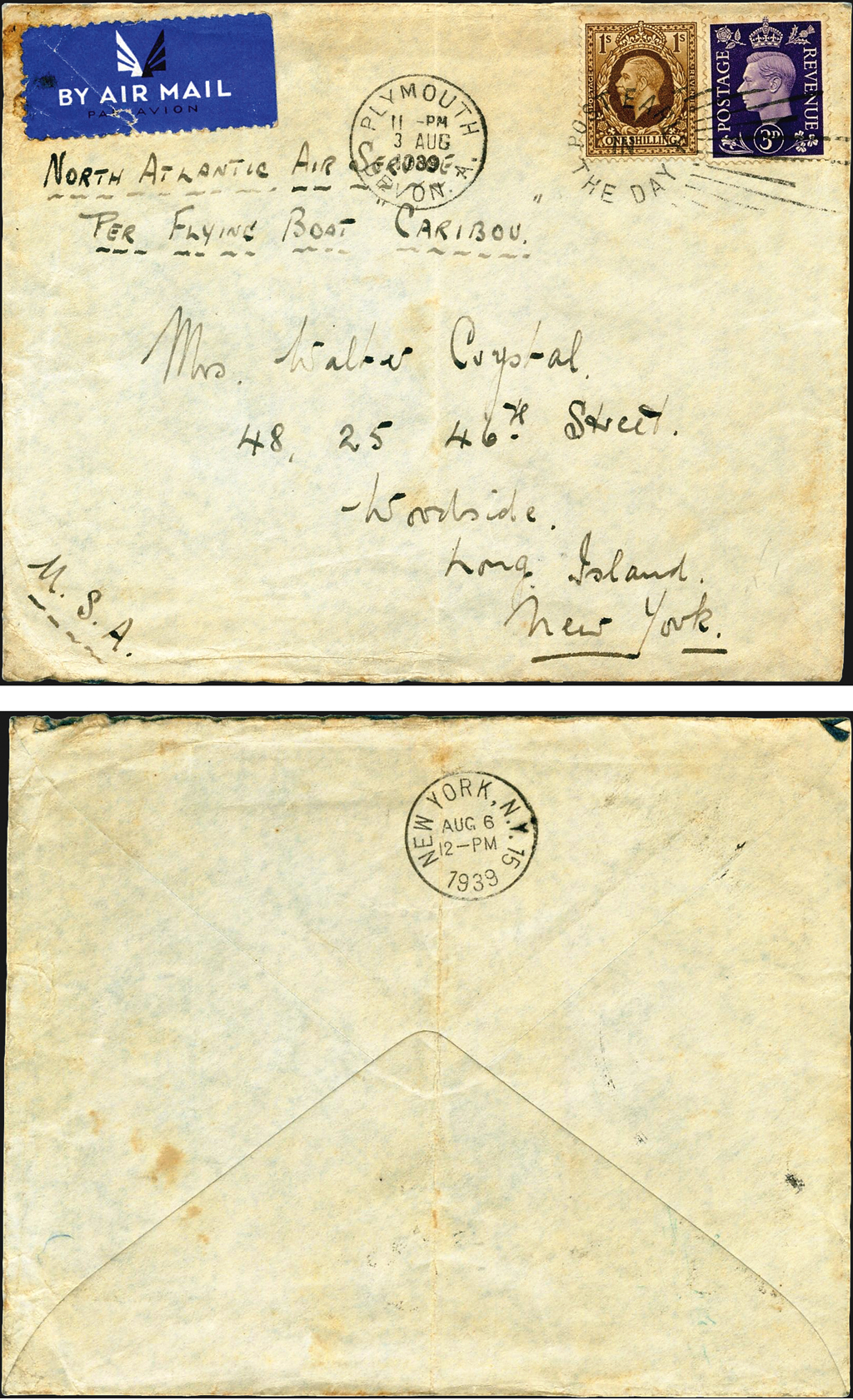

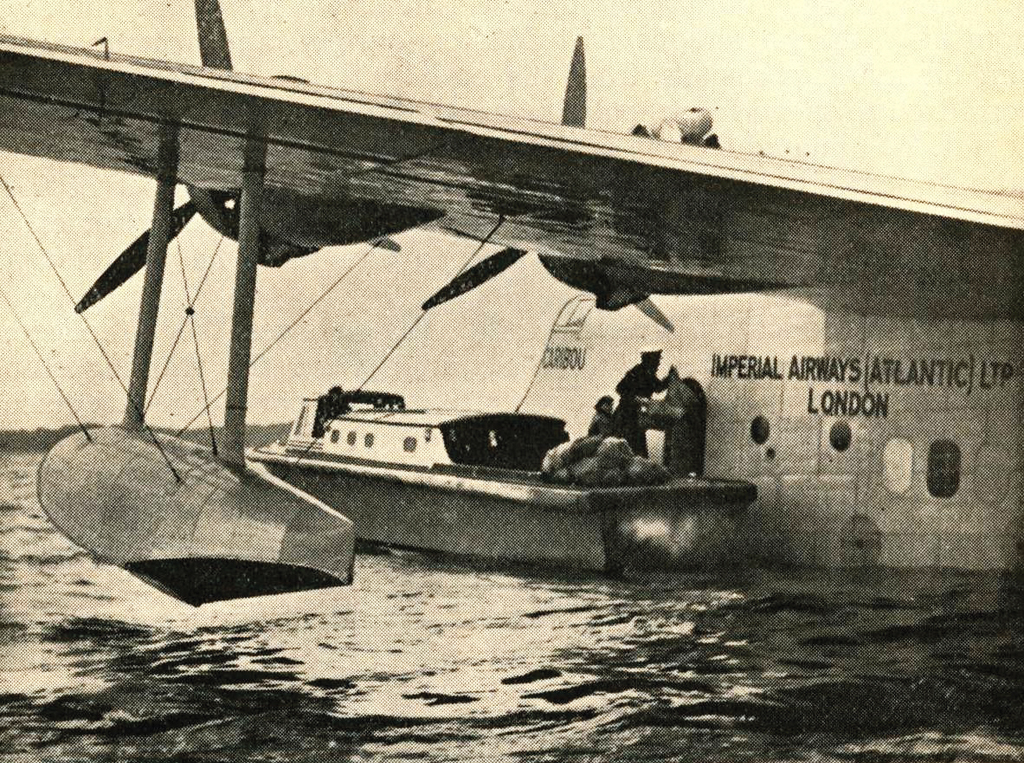

On the Imperial Airways trans-Atlantic route, two Short S-30 flying boats, Caribou and Cabot, took turns making the round trip, so that one was flying east while the other flew west. Having begun so late in the summer, only eight trips in each direction were possible before October, when adverse weather conditions closed the North Atlantic crossings.

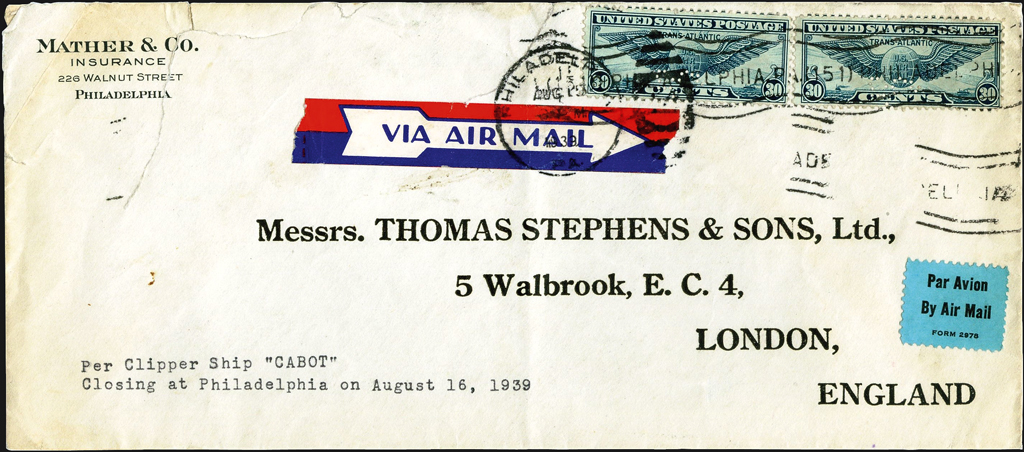

Aero Field listed the flights: “England-U.S.A. Aug. 5th, 12th, 19th, 26th, Sept. 3rd, 9th, 16th, 23rd. U.S.A.-England, Aug. 9th, 16th, 23rd, 30th, Sept. 6th, 13th, 20th, 28th.” As Cabot departed New York on Aug. 30, war broke out in Germany, and by the time she arrived at Southampton, Britain was a belligerent.

It isn’t easy to identify covers carried on these flights unless they have postmarks of Montreal. In almost all other cases, collectors in both North America and in Europe habitually classify trans-Atlantic covers between the continents as Pan Am FAM 18 mail. But other clues are available for astute searchers. My Aug. 15 cover was endorsed for the next day’s Cabot departure.

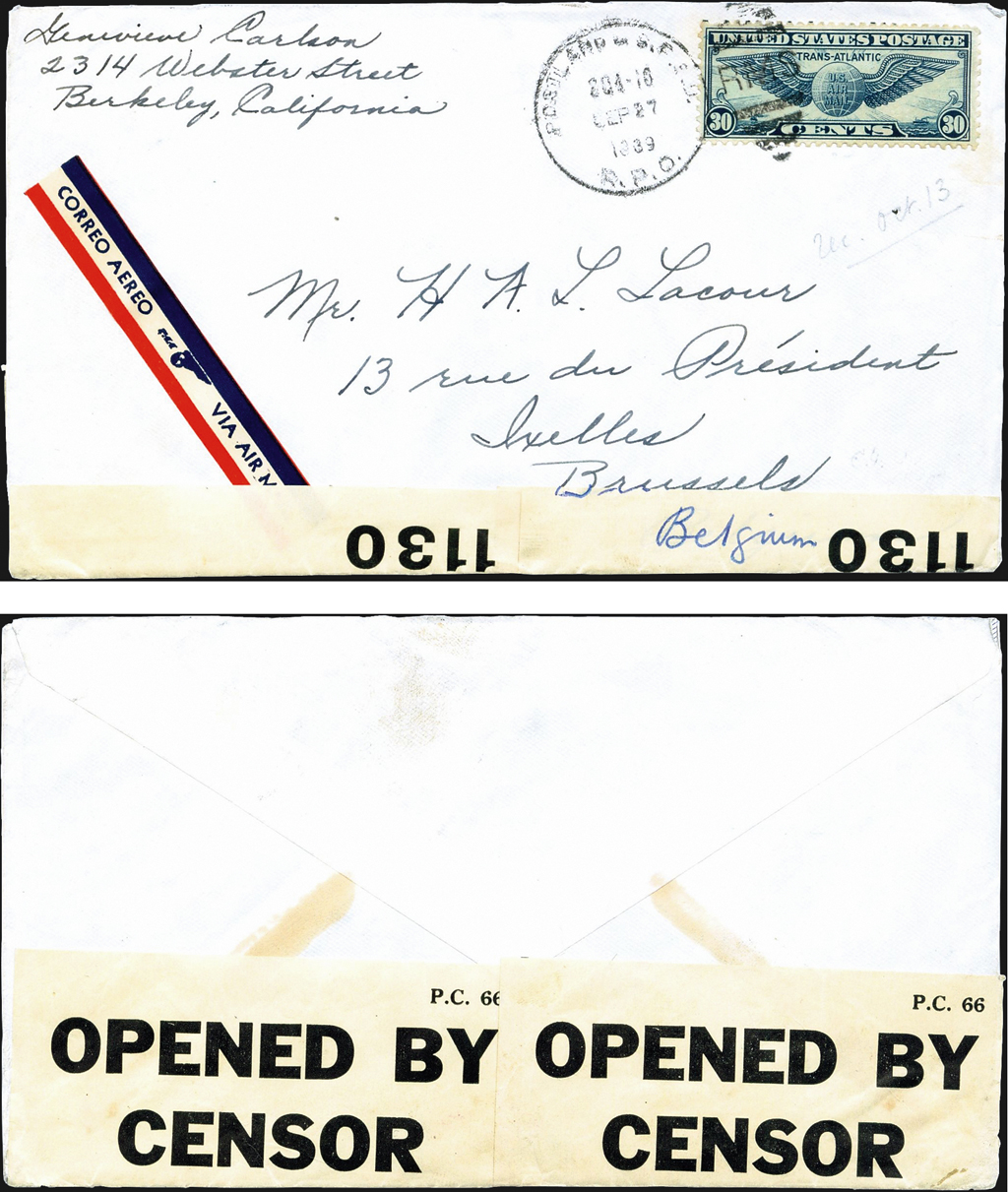

My airmail cover from Berkeley, Calif., to Brussels, Belgium, canceled Sept. 27 at a Portland & San Francisco railway post office, probably connected to the last Imperial Airways flight from New York.

The evidence is the P.C. 66 Imperial Censorship tape, which sealed the envelope after the contents were examined at London.

Both Caribou and Cabot were transferred to the Royal Air Force, and both were destroyed by German forces during the failed British attempt to prevent the Nazi conquest of Norway.

Nevertheless, British Overseas Airways, the successor to Imperial Airways, renewed the trans-Atlantic service in August 1940 with Short S-30 flying boats Clare and Clyde.

Related posts from Linns.com

BOAC Trans-Atlantic Flights in 1940

The purpose of the service was mainly its propaganda value, not its passenger or mail service. As the February 1941 Air Mail Magazine explained:

During the summer and autumn [of 1940] the Trans-Atlantic flights of Clare and Clyde, which started at the height of the invasion crisis [of the Low Countries and France] and were completed after ten crossings without incident or interruption helped greatly to persuade the world that Britain was strong and confident in the air, and that German claims of an aerial blockade were false. Special arrangements were made by British Airways to ensure that on each flight the latest editions of English daily newspapers were carried.

Phillips somehow got word in time to prepare souvenir covers for Clyde’s Aug. 3 departure, which were flown from England to Newfoundland and Canada, and from Montreal to England on the Aug. 8 return flight. He offered all three for sale to subscribers, but eventually deleted the ones to Newfoundland because they were never returned.

I have not found any of Phillips’ BOAC first flight covers, but I do have a cacheted Aug. 8 cover from Newfoundland to England. The October 1940 Aero Field reported an Aug. 8 cover from Montreal backstamped Aug. 13 at Belfast in spite of having been held for censorship along the way.

American newspapers gave plentiful coverage to Clare’s arrival at La Guardia Field, including photographs of the camouflage-painted flying boat tethered to its mooring buoy, and of its celebrity passenger, the American spymaster Col. William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who had been on a secret mission to England for the Secretary of the Navy.

Five BOAC round trips and their mails

Souvenir covers from that flight can seem surprising because published reports of the loads carried on both eastbound and westbound trips recorded only diplomatic mail and newspapers. But as Norman Baldwin wrote in the February 1941 Aero Field:

Exact details of mails flown are exceedingly difficult to unearth under war conditions when essential facts are necessarily shrouded at the time they occur and postal officials are so overloaded with extra work that it is unreasonable to expect their help after sufficient time has elapsed to satisfy censorship restrictions.

However incomplete they may be, Baldwin’s reports have helped me in my searches, so I shall summarize them here:

The first westbound flight of the Clare left England and Ireland Aug. 3 and arrived at New York Aug. 4. It carried diplomatic mail and London newspapers for Canada and the United States.

The first eastbound flight of the Clare left New York Aug. 8 and arrived at Ireland and England Aug. 10. It carried 15 pounds of diplomatic mail from New York.

The second westbound flight of the Clare left England and Ireland Aug. 14 and arrived at New York Aug. 15. It carried 115 pounds of diplomatic mail and newspapers for the United States.

The second eastbound flight of the Clare left New York Aug. 18 and arrived at Ireland and England Aug. 20. It carried 50 pounds of diplomatic mail from New York.

The third westbound flight of the Clare left England Aug. 26 and Ireland Aug. 30, and arrived at New York Aug. 31. It carried 200 pounds of diplomatic mail for the United States.

The third eastbound flight of the Clare left New York Sept. 4 and arrived at Ireland and England Sept. 6. No mail was recorded.

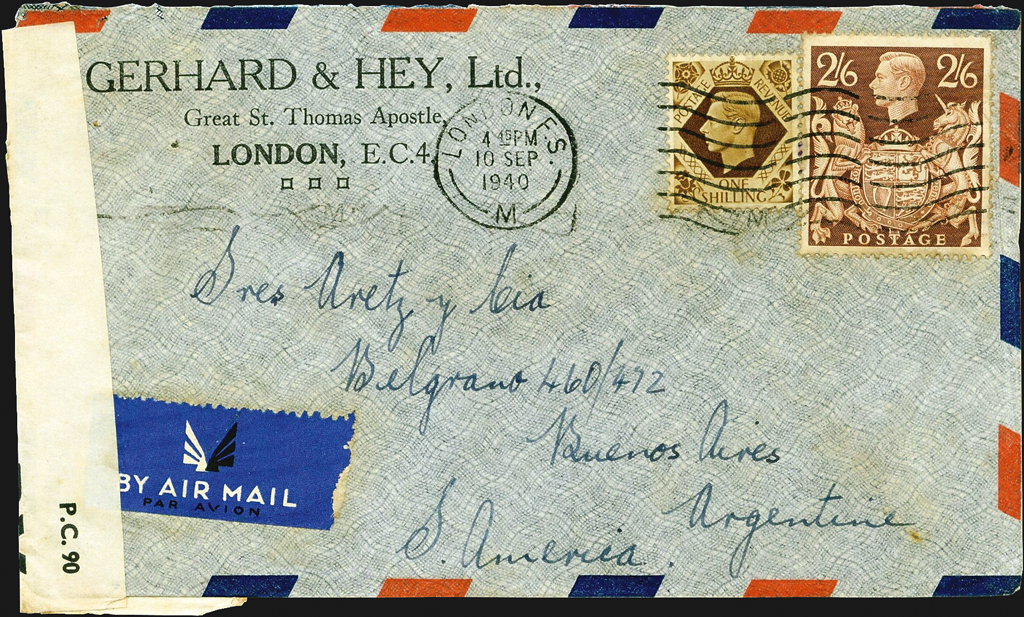

The fourth westbound flight of the Clare left England Sept. 13 and Ireland Sept. 15, and arrived at New York Sept. 16. It carried two pouches of diplomatic mail and three large pouches of ordinary mail and newspapers.

The fourth eastbound flight of the Clare left New York Sept. 21 and arrived at Ireland and England Sept. 23. It carried two pouches of diplomatic mail from New York.

The westbound flight of the Clyde left England and Ireland Oct. 4 and arrived at New York Oct. 5. The eastbound flight of the Clyde left New York Oct. 9 and arrived at Ireland and England Oct. 11. Baldwin was unable to learn whether mail was carried on either trip.

From these reports, one can see that the most likely source of BOAC trans-Atlantic covers would have been Clare’s Sept. 13-15 westbound flight. My airmail cover to Argentina, posted Sept. 10 at London, censored there, and flown to New York for a Pan Am connection to South America, is a probable example. The BOAC flight would have been faster than Pan Am flights nearest to that schedule.

Imperial Airways and BOAC epilogue

Clyde’s October 1940 round trip was the final BOAC trans-Atlantic flight until July 1946, when service resumed using land-based Lockheed Constellation airplanes. Both Clare and Clyde were next assigned to Africa service.

In October 1941, Clare reopened trans-Mediterranean service via Gibraltar and Malta to Cairo that had been suspended after the fall of France, and flew secret weekly missions in relief of Malta during the winter of 1941-42.

On Feb. 15, 1941, a fierce storm tore Clyde from her moorings at Lisbon, causing such extensive damage that she could not be repaired. On Sept. 14, 1942, Clare was destroyed by fire in the ocean off Bathurst, Gambia, on a return flight from Lagos, Nigeria, a tragedy that left no survivors.

When the time comes to revise and expand the “Foreign Flag Flights” chapter for a future edition of the American Air Mail Catalogue, perhaps some of the information presented here will find its way into the listings. Meanwhile we can all enjoy an excellent first effort.

More from Linns.com:

USPS announces joint issue with Japan in April

Rate change approved by Postal Rate Commission

Washington coil error discovered on flat-rate envelope used to mail APS circuit books

Where's the moose? Regency-Superior kicks off 2015 with the sale of a missing-moose error

Linn’s columnist John Hotchner responds to criticisms of U.S. program proposals

Keep up with all of Linns.com's news and insights by signing up for our free eNewsletters, liking us on Facebook, and following us on Twitter.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers

-

World Stamps

Oct 5, 2024, 1 PMCanada Post continues Truth and Reconciliation series