World Stamps

Acquiring the holy grail: Great Britain’s £5 orange Queen Victoria

By David Alderfer

The 1882 £5 orange Queen Victoria high value (Scott 93) is known to many collectors who specialize in Great Britain as the holy grail of British stamps.

In May, I acquired an example of this sought-after stamp.

When I began collecting Great Britain stamps more than 35 years ago, the £5 orange Victoria was my ultimate desire.

However, I believed that it was unlikely that I would ever possess one. Its cost, several thousand dollars for a used example, seemed prohibitive. A mint example was out of the question.

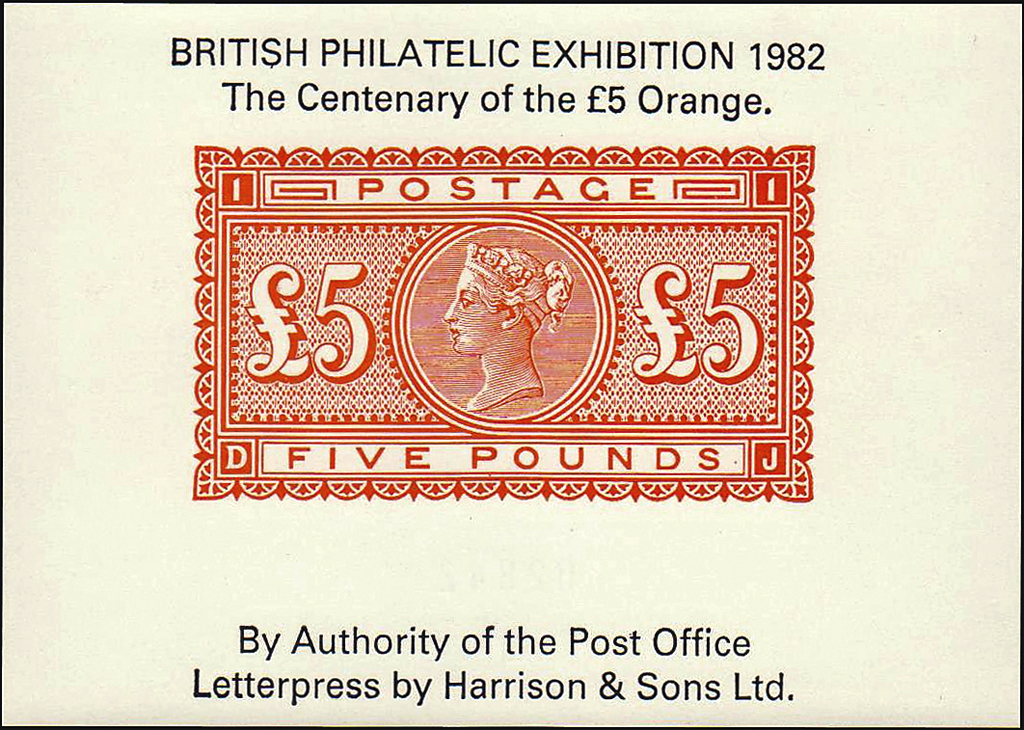

For more than three decades, I settled for the reproduction printed by Harrison and Sons as a souvenir of the 1982 British Philatelic Exhibition in London.

The image, though taken from a genuine £5 stamp lettered DJ in the two lower corners, shows considerable loss of the fine detail of an original stamp.

Now I am retired. Major expenses of living such as house, car and retirement savings are fulfilled. An inheritance from my father — also an avid stamp collector — finally made it financially possible for me to consider buying an example of this stamp.

A trip to London in May to attend the Europhilex stamp exhibition gave me an opportunity to shop and select from among about 50 used examples that dealers offered for sale.

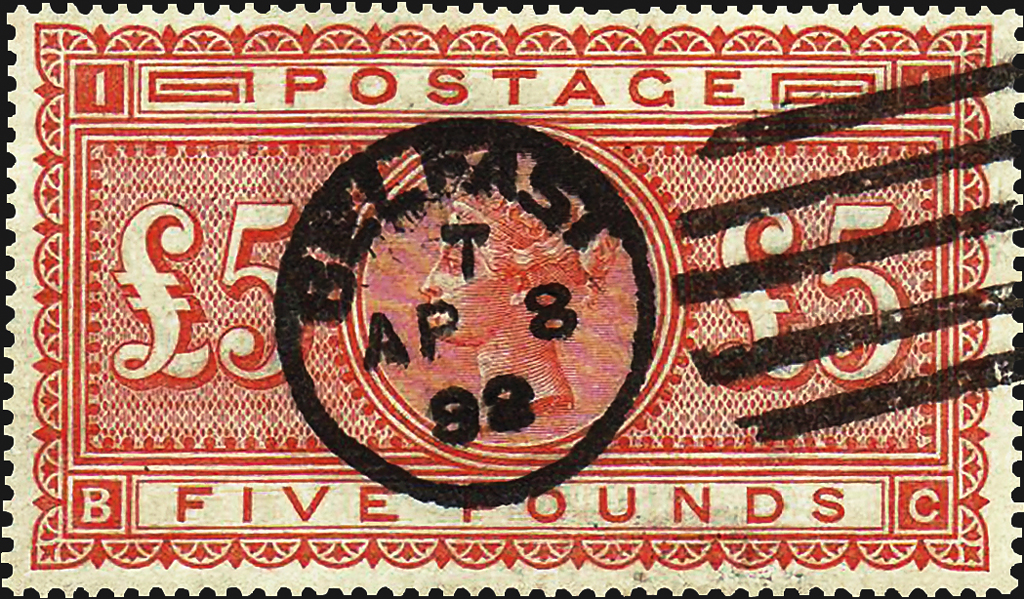

I found and purchased the £5 orange Victoria shown nearby, paying $2,370.

Before putting out that much money, I did research on my intended purchase.

The definitive research on the £5 Victoria is an award-winning 312-page, hardbound, color-illustrated book published in 2013 by Stanley Gibbons Ltd., titled The £5 Orange by John Horsey. It costs £75 (about $112).

The £5 orange started out as a telegraph stamp, not a postage stamp.

In the 1880s, rates for some overseas telegrams were very high.

Telegrams to Bermuda, for example, cost £1, 4 shillings and 4 pence per word (£1.4s.4d).

A message of just four words cost more than £5, hence the need for a £5 telegraph stamp to receipt payments of high charges.

On Oct. 31, 1881, the special series of labels designated to receipt payments of telegrams was withdrawn from use. Thereafter, postage stamps were used to receipt payment of telegrams.

Because there was no £5 postage stamp and because high-cost telegrams were still being sent, the post office decided to print its first £5 postage stamp, which could also be used to receipt telegrams.

To save the cost of making a new design and plate, the post office took the plate that had been used to print £5 telegraph stamps and modified it to print £5 postage stamps.

The modification was to mill out the word “Telegraphs” over the profile of the queen and make a second plate to print the word “Postage,” flanked by key pattern ornaments, to fill the wide space left by the deletion of “Telegraphs.”

Very few of the high-value postage stamps were actually used to pay postage.

Horsey identifies and illustrates only three examples for which a “beyond doubt” postal use can be proven.

Of the 2,712 used examples he examined, only three were likely applied to heavy, registered parcels commanding high postage.

Most used £5 orange Victoria postage stamps in the hands of collectors were used to receipt telegrams after the telegraph version was withdrawn from use.

These often bear boxed cancels in addition to circular datestamps of the sending telegraph offices.

Many examples of the box cancels bear the abbreviation T.A.B., which stands for Telegraphs Accounts Branch.

A second popular use of the postage version was internal accounting.

The stamps were used to receipt bulk mail payments so customers could pay total postage due without having to apply individual stamps to hundreds, sometimes thousands, of the same item.

According to Horsey, the cancellation on my used £5 postage stamp shown with this column indicates the stamp was likely used to receipt the payment in Belfast of excise tax on whiskey or tobacco.

Serendipitously, I met Horsey in front of his five-frame £5 orange Victoria exhibit at Europhilex in London in May.

We introduced ourselves, and then he commented on noteworthy features of his exhibit.

Our exchange was most cordial, as often are conversations between fellow stamp collectors about their passions.

Horsey’s well-researched and illustrated book gives many interesting facts about this classic British stamp.

For example, only 246,759 stamps were issued to post offices for use over its life of 21 years.

He estimates that around 8,000 are still in existence today. This is a relatively small number of surviving examples, which is one reason the stamp commands high prices.

Most of these survivors were illicitly liberated from security waste paper scrap intended for destruction by pulping.

Acquiring the holy grail is a milestone. Acquisition brings with it a great deal of satisfaction and pride of place. But I also feel a dream, a lifelong challenge, has ended. What now?

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers