World Stamps

Linn's attends sneak preview of British Guiana 1¢ Magenta

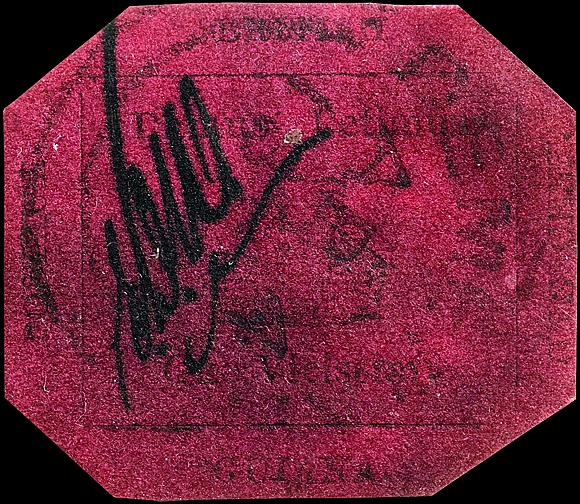

The world’s most valuable stamp, the unique 1856 British Guiana 1¢ Magenta, will be exhibited in Washington, D.C., beginning June 4. The identity of the stamp’s owner will be revealed that day as well.

It is not a pretty stamp, as many of its commentators have noted.

The once crisp magenta ink is faded to what seems a dull pink.

The stamp itself is tiny, slightly bigger than a United States definitive but smaller than a commemorative. This makes its Latin lettering difficult to read, even with a magnifying glass.

Even more surprising, some of the owners have written their initials on the back.

This is the 1856 British Guiana 1¢ Magenta, the world most valuable stamp. After being hidden from public view for almost 30 years, it went on display at the National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C., June 4.

The famous stamp's latest owner, shoe designer Stuart Weitzman, was revealed by the NPM the same day.

Along with a small number of donors to the museum, this writer was privileged to hold the stamp briefly at a sneak preview May 8.

To be sure, the stamp was sealed in a small plastic case and it was closely guarded. Still, even that is closer than most collectors will ever get.

It’ll be shown in a specially constructed case that will allow visitors to see both sides of the stamp.

And there will be materials explaining what has made this tiny stamp the world’s most-sought stamp.

Linn’s was allowed to attend the preview, but no photography was allowed.

The plastic case, we were told, had been used at one of its celebrated auctions where the stamp was shown.

At the museum, a staffer carried the stamp around the atrium where we were seated. He was followed by another staffer who had another tablet that some guests assumed was an electronic monitor for the case holding the stamp.

Whatever the aide was carrying museum director Allen Kane was ecstatic about the stamp.

The tiny stamp, he announced to the handful museum guests, was probably the most valuable item “by weight” of any item in the Smithsonian Institution’s vast holdings.

But the problem with the 1¢ Magenta is, as Irwin Weinberg of Wilkes-Barre, Pa., one of the stamp’s former owners, said: “Because of the money involved, once you own it, it owns you.”

The truth is that Weinberg was pretty successful in exploiting the famous stamp.

The Pennsylvania stamp dealer and a group of investors bought it in 1970 for $280,000. A decade later they sold it for $935,000.

“For 10 years I took it around the world and the press was very cooperative,” Weinberg said.

With a tan briefcase and a pair of old police handcuffs, Weinberg would secure himself to the case and transport the 1¢ Magenta to stamp shows around the world.

In the process, he secured reams of newspaper clippings about the stamp and the high-rollers of the stamp world.

“In those days it was dynamite,” he said.

Among those clippings was a Life magazine story, which I can remember from my teenage years.

It was there that I first saw the stamp or color photographs of it. It was scarlet red in those days.

Weinberg retained a role in promoting the stamp after it was sold to John E. du Pont, an heir to his family’s chemical fortune.

He had remained anonymous after securing the stamp in a New York auction in 1980, but his identity as the owner became public later.

But du Pont, a well-known stamp collector, ran afoul of the law.

He was imprisoned for the 1996 murder of an Olympic gold medal wrestler, who had been working on the billionaire’s sports interests.

For years after his conviction, du Pont refused to consider pleas from stamp groups to display the 1¢ Magenta.

Museum director Kane was one of those who contacted du Pont’s lawyers seeking the stamp. “John won’t see you,” Kane said the lawyers told him.

“If you’ll get him a pardon, he’ll give you the stamp,” Kane said he was told.

“I tried to get the stamp and I failed to get the stamp,” Kane said. But Kane never gave up the quest.

On Dec. 9, 2010, Du Pont died in a Pennsylvania prison at the age of 72.

His estate subsequently sold his stamps, including the 1¢ Magenta.

After a celebrated New York auction in June 2014, it was purchased by another individual who announced he wished to remain anonymous.

A former Postal Service executive who was not a stamp collector when he was named head of the postal museum, Kane remained determined to get the stamp — at least on a long-term loan.

He had done that with stamps from the collection of Queen Elizabeth II and from the New York Public Library, which had the famed Benjamin K. Miller collection of U.S. stamps.

To Kane’s delight, the new owner’s agents approached the Washington museum and the British Library in London.

Both were asked to tell what they would do if they were loaned the stamp.

Kane said his staff devised “a helluva good proposal” for putting the stamp on display in Washington, as well as moving it to other cities for short-term displays.

Part of the winning proposal was for the innovative way Linda Edquist, manager of the museum’s preservation office, proposed to display the stamp.

As she explained to the small group of collectors, “I want every visitor to see the one cent magenta.”

That posed “a very challenging task,” she said, because the stamp is so small and not easy to see.

But by building a special case made of what she called “smart glass,” visitors should get a good view of the stamp.

The smart glass enables an item to be displayed without suffering the ills of natural sunlight, which is the enemy of many paper exhibits.

This is the same technology that the museum used to display an envelope that contained anthrax spores and that was mailed to former Sen. Thomas Daschle of South Dakota.

The letter was part of a display on the U.S. Postal Inspection Service and won praise for being “ahead of the game” of museum displays, Edquist said.

Hopefully, most collectors who see it in Washington won’t react like Weinberg did when he first saw the stamp in a glass case at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

“I never gave it another thought,” said Weinberg, who would later devote much of his life to promoting the tiny stamp he would buy almost 40 years later.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers