World Stamps

Canada’s early 19th-century Numeral cancels by the numbers

By Fred Baumann

As with most territories where mail mattered before postage stamps came on the scene, British North America prior to 1851 applied a diverse and occasionally bewildering array of manuscript and hand-struck postal markings to its pre-stamp mail.

The best place to see a wide range of these markings in one volume may still be Frank W. Campbell’s Canada Post Offices 1755-1895, published in hardcover in 1972.

The arrival of postage stamps largely ended the tedious task of calculating and writing common postal rates on each letter, but it added a new responsibility to the postal clerk’s duties: that of canceling the stamps.

In the first decades of stamp use, postal administrations lost sleep over the prospect of crooks figuring out ways to clean canceled stamps. Protecting post-office revenue with permanent postmarks was thus a high priority for many years, with consequences visible on most mail of the period.

In 1958-59, Grant Showers of the British North America Philatelic Society wrote a four-part series in BNA Topics titled “Obliterations and Cancellations Between 1851 and 1900,” intended as an overview for collectors new to Canadian postal history.

I have made use of some of his research and dates in my truncated treatment here, but you can read the original series courtesy of the British North America Philatelic Society through its Horace W. Harrison Online Library.

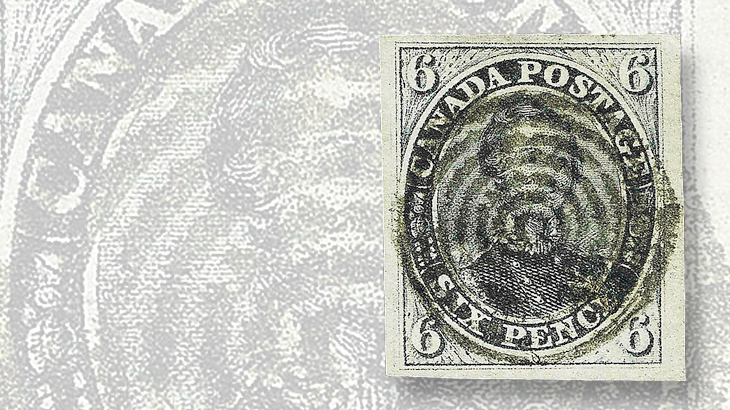

The earliest cancels comprised concentric rings, and are often called target cancels. A particularly nice strike is seen on the 1851 6-penny grayish purple Prince Albert on laid paper (Scott 2) illustrated nearby.

Showers wrote: “The concentric ring obliteration was the first official post office issue, and was first

used in April 1851. They [sic] were cut individually and showed great variation. The early types contained from five to seven rings and the later types contained one to four rings, but all were used concurrently.”

He added that he had seen strikes of these cancels in black, blue, red, green and pink, and purple or violet.

A case in point is the 1855 cover front to C.T. French, Esq., in South Potsdam, N.Y., shown nearby The cover is franked with a vertical pair of imperforate 3-penny Beaver stamps on wove paper (Scott 4) paying the cross-border rate.

The stamps are canceled with seven-ring cancels inked in green, the same ink used on the circular datestamp from Portage-du-Fort, C.[anada] E.[ast] (now Quebec), located on the east shore of the Ottawa River.

These early cancels are “mute,” meaning that they did not include any information, such as date or location.

What followed these mute target cancels were target cancels that weren’t mute, but had a number that corresponded to the post office at which they were used.

If there is a stamp-issuing entity on our planet whose collectors can resist the challenge of chasing numbered cancels used in this way, I have yet to hear of it. Canada is no exception.

Showers’ first article gives the date for the introduction of these handstamps with “four-ring numeral” cancelers as March 1, 1857.

“At that time, there were over 1,200 post offices in Canada but only certain money order post offices got this marking,” he wrote. “The numerals were issued alphabetically (1-52). Number nine was not issued, so as not to confuse it with six. Toronto, being the headquarters at the time, did not have a number.”

For those expecting crisp strikes of bold black numbers you can read from across the room, these early four-ring numeral cancels can be a bit disappointing, as you can see on the three stamps nearby.

This isn’t chiefly due to any defect in the postmarks, but to the relatively dark and heavily inked designs of most early Canada stamps.

The three examples are from Ontario, then called “Canada West” or “Upper Canada,” the latter a reference to its position on the St. Lawrence River (“Lower Canada,” now Quebec, being downriver).

Shown, from left to right, are: the four-ring numeral cancel “17” of Ingersoll on a rare laid paper 1868 1¢ brown-red Large Queen (Scott 31), the “19” of London on an imperforate 1857 7½d green (Scott 9), and the “33” of Port Hope on an exceptionally well-centered 1858 3d Beaver (Scott 12).

The 2014 Unitrade Specialized Catalogue of Canadian Stamps includes a brief table of these cancellations with “rarity factors for usage on the 1859 issues.” These generally mirror the population at the time, which presumably reflects the likely volume of mail.

The ratings go from a one for common to 10 for extremely rare.

The largest of the towns in the three examples was London, incorporated as a city of more than 10,000 in 1855. Unitrade rates most of London’s four-ring numeral cancels as a four, which falls into the “very scarce” range.

However, the “19” of London struck in blue is regarded as “extremely rare,” or a 10, with only two examples recorded.

The four-ring numeral cancels of Port Hope are rated a seven for “rare.”

Four-ring numerals from the two principal cities of Quebec are represented here on imperforate Beaver multiples (Scott 4): the common “21” of Montreal on an 1857 3d deep red strip of three on thick, hard paper, and the scarce “37” of Quebec City well struck across a pair.

Finally, what of Toronto, which did not have a number because at the time it was the headquarters of Canada’s postal service?

Toronto mail was canceled with a diagonal grid pattern struck in small, numberless squares, seen here on another pair of imperforate 3d Beavers (Scott 4).

With the issuance of stamps in Canadian dollars and cents in 1859, the arrival of Confederation in 1867, and the issuance of the Large Queens — the first issue of the Dominion of Canada — in 1868, a new set of numeral cancellations would come into use. But that is another story for another day.

My sincere thanks to Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries for the use of images from its website in this column.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers