World Stamps

Dictators on stamps of the world: absolute power corrupts absolutely

By Rick Miller

Dictator is defined as a ruler with total power over a country.

We owe this term to the ancient Romans. In the Roman Republic (509-27 B.C.), a dictator was an extraordinary magistrate appointed by the senate in times of emergency.

Roman dictators were given absolute power for a limited time and a specific purpose, such as leading an army against an invasion or enemy.

The dictator ruled by decree, creating or abolishing laws by dictat — that is by signing an executive order without benefit of legislative support.

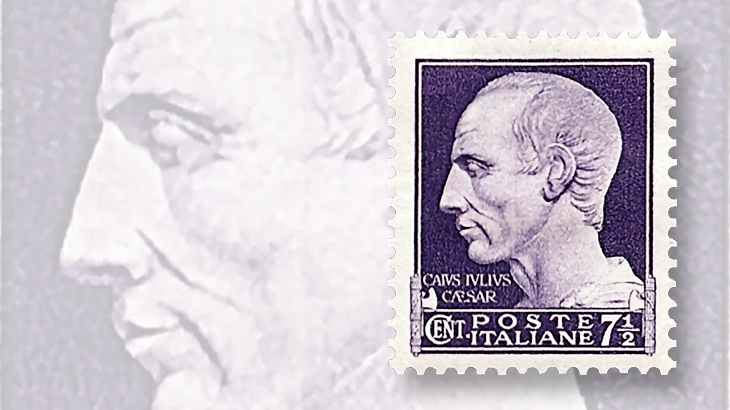

Once the emergency was over, the dictator’s term was ended and normal governance resumed. The last and most famous Roman dictator was Julius Caesar. In 46 B.C., he was appointed to serve 10 consecutive one-year terms as dictator.

In February 44 B.C., the senate appointed him dictator in perpetuity. In that case, perpetuity lasted for only one month, as he was assassinated on the Ides (the 15th) of March.

After the Roman Republic, the term dictator generally lay fallow until the 19th century, because most geopolitical entities were either monarchies or colonies, with a few republics scattered here and there.

The proliferation of republics, coupled with the rise of nationalism and independence movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries, saw the far more common emergence of the dictators.

Not yet a pejorative, it was considered an admirable enough term that the Studebaker Dictator was a line of sedans produced by that American automobile company from 1927 to 1937.

However, the 20th century saw a series of mass murders carried out by dictators that forever associated the title with infamy.

The most notorious mass-murdering dictators and estimates of the numbers of their victims are Adolf Hitler (8 million to 12 million), Joseph Stalin (40 million to 50 million), and Mao Tse-tung (approximately 78 million).

Though not as well known, many other dictators have sunk their teeth into a hapless nation and had their visages plastered on postage stamps.

One of the more interesting minor dictators of the 20th century was Enver Hoxha of Albania.

Hoxha was born in Albania in 1908, while it was still a province of the Ottoman Empire.

The son of a wealthy cloth merchant, he was educated in France, where he became a communist. He was teaching grammar school when Albania was invaded and conquered by Italy in 1939.

Hoxha helped organize the communist partisan resistance and was elected first secretary of the Albanian Communist Party in 1943.

The partisans liberated Albania in November 1944, and Hoxha became prime minister. In 1944, Hoxha broke with Josip Broz Tito and the Yugoslavian communists over the issue of Kosovo.

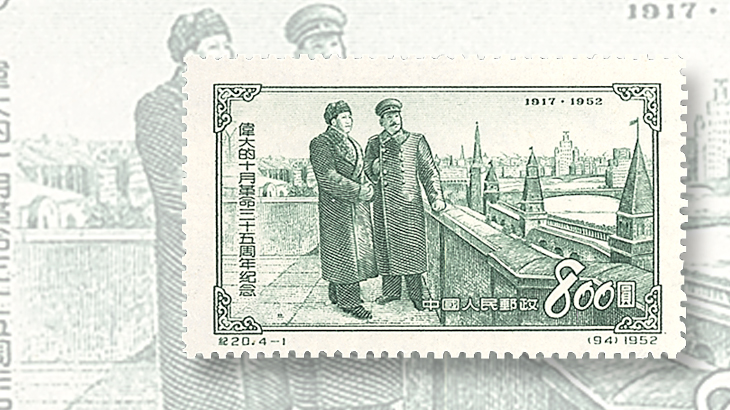

A great admirer of Josef Stalin, Hoxha kept Albania closely allied to the Soviet Union until after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Viewing Khruschchev and company as revisionists who had abandoned the true path to communism, Hoxha eventually broke with the Soviet Union and allied Albania to the People’s Republic of China under Mao Tse-tung.

Relations with China soured after Chinese rapprochement with Tito’s Yugoslavia and Chinese reduction in aid to Albania.

Hoxha then declared China also to be a revisionist state, with Albania as the only true remaining Marxist-Leninist state in the world.

Internally, Hoxha’s regime was one of the most repressive in the world. Religion was ruthlessly eradicated. Archbishops, bishops, priests and nuns were tortured and executed in mass. A total of 2,169 churches and mosques were demolished.

All private property was confiscated, and landowners, merchants and recalcitrant peasants were executed.

All contact with the outside world was cutoff because people attempting to enter or leave Albania were summarily executed.

The secret police were everywhere, and every stray comment was recorded.

The Albanian Communist Party was regularly purged, with possible rivals eliminated before they became too powerful.

Industrialization, initially sparked by aid from the Soviets and China, fell by the wayside when aid was cut off. By the time of Hoxha’s death in 1985, Albania was the poorest country in Europe and one of the most backward nations in the world.

After his death, Hoxha’s body was initially housed in an enormous white pyramid-shaped mausoleum and shrine designed by his daughter.

After the fall of communism, his body was removed and buried, and the former mausoleum now houses the International Cultural Center.

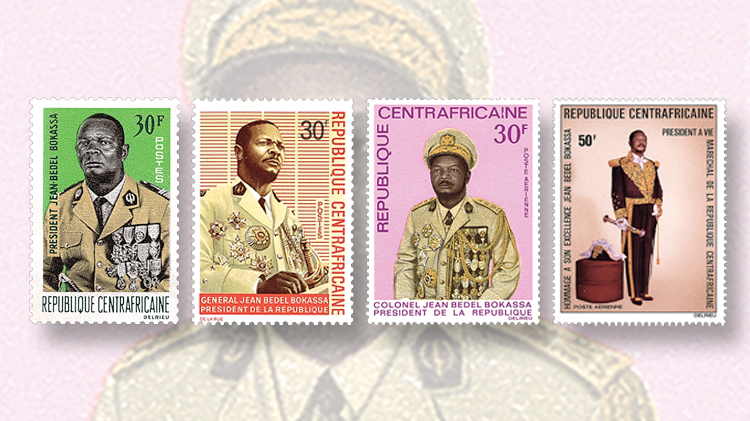

To illustrate paranoid megalomania in the dictionary, there could well be a picture of Jean Bedel Bokassa.

Bokassa was born Feb. 22, 1921, in French Equatorial Africa. When he was 12 years old, his father was beaten to death for resisting French authorities, and his mother committed suicide. Orphaned, he was sent to a French Roman Catholic mission school.

In 1939, he enlisted in the French colonial military. He fought for the Free French forces in Africa, France and Germany in World War II, and was promoted and decorated for heroism.

After the war, he was sent to officer training school and was commissioned as an officer. He fought for the French in Indo-China, attaining the rank of captain.

After the former French colony of Ubangi-Chari gained independence as the Central African Republic in 1960, he left the French army in 1962 to accept a commission in the new republic’s army. A cousin of President David Dacko, he was soon the country’s top military commander.

On Dec. 31, 1965, Bokassa led a coup and seized control of the government. He abolished the constitution, dissolved the national assembly, and instituted his personal and absolute rule.

Bokassa personally tortured and murdered political opponents and fed some of them to the lions and crocodiles in his private zoo. Although officially Roman Catholic, he had 20 wives and 62 children.

Rumored to be a cannibal, he often stored body parts of his victims in walk-in freezers in the palace. When the economy collapsed and people rioted demanding food, the rioters were massacred.

In 1972, Bokassa declared himself president for life. On Dec. 4, 1977, he crowned himself Emperor Bokassa I and changed the name of the country to the Central African Empire.

He spent more than $20 million on his coronation, which was more than the country’s annual gross national product.

He idolized Emperor Napoleon I of France and dressed his personal guard in Napoleonic-era French military regalia.

The end of his rule came in April 1979, when about 100 elementary school children who protested in Bangui over being forced to buy expensive school uniforms from a company owned by one of his wives were arrested and murdered.

International outrage and French military intervention forced him into exile in France, where he lived off the fortune he pilfered while in office.

Returning to the Central African Republic in 1986, Bokassa was arrested and tried for murder, cannibalism, treason and embezzlement. He was found guilty of all charges except cannibalism, of which he was acquitted on a legal technicality, and was sentenced to death.

The sentence was later commuted to life in prison. He was released from prison under a general amnesty Aug. 1, 1993. He died peacefully in Bangui Nov. 3, 1996.

Dictators come and dictators go, but Lord Acton’s dictum remains: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers