World Stamps

Identifying Belgium’s first stamp issue: the Epaulettes of 1849

By Sergio Sismondo

In the December 21, 2015, Linn’s monthly, I mentioned determined officials in London — early exponents of the adage “what is good for business is good for the country” — who put through a bold and astonishing postal reform that brought down rates, sometimes as high as 16 pence, uniformly to a single penny.

In the Jan. 18 Linn’s, I wrote about equally determined administrators in Rio de Janeiro who, having studied the English experiment, did essentially the same: a postal reform involving compulsory prepayment of postage and the issuance of postage stamps, a reform fully implemented, half a world away, just three years after the English.

I also mentioned there were Swiss officials in Zurich who printed stamps for prepayment of postage in their canton in 1843. They were followed quickly by their counterparts in Geneva (1843) and Basel (1845). The Swiss were carefully, slowly, inching toward a national system of posts “a l’Anglaise.”

Connect with Linn's Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

Meanwhile, the subject of postal reform was gaining currency in other European capitals. Business people wanted it, but ministers of finance were afraid of consequences. “It worked in London, the largest city in the world; it cannot work in our little city, there is no base for it,” said cautious bureaucrats in Brussels.

One functionary felt differently. Louis Bronne, inspector of the Central Administration of the Belgian Post Office, sympathetic to the events unfolding in England, was chosen to travel to London in February 1841 to investigate closely the functioning of the reformed post office and the veracity of claims of economic benefits that ensued.

He returned to write an extremely positive review and recommended the adoption of all aspects of the system for the Belgian post office, without qualms. Specifically, Bronne recommended the printing of stamps and postal stationery for the prepayment of postage.

Bronne’s report apparently carried some weight; a commission was set up in great haste by the minister of Foreign Affairs and minister of Public Works to study the matter in more depth. The commission began its work in April 1841 but did not reach a decision, and a report was not forthcoming.

Four years went by, and reform seemed to have been forgotten. Hoping to move things along from the sidelines, the merchants of Brussels, frustrated and well-informed, took matters under their wings.

They set up a second commission on postal reform, but everything related to reform seemed to stall. Perhaps those afraid of consequences found one obstacle after another to block progress.

Two more years passed with no progress. Then, in late 1847, the merchant’s views were circulated in high levels of government. The legislature accepted the proposals made by business, and on Dec. 24, 1847, just in time for Christmas recess, the Belgian Senate adopted a set of postal reform laws. The three principles — uniform charges, prepayment of postage, and introduction of postage stamps — had finally become the law of the land.

But interminable stalling tactics continued. It took two more years for a decision to implement these laws. Another enactment, of April 1849, was necessary to change the postage fees, and the first stamps were adhered to letters on July 1, 1849. “Better late than never,” they say.

As the commission of merchants had recommended, internal postage rates were in simple and logical progression based on 10 centimes for a single-weight letter sent to a distance of 30 kilometers or less, and 20 centimes for a distance of more than 30 km. Multiples of weight were charged equivalent multiples of these two rates. Thus a triple-weight letter traveling 50 km was charged 60 centimes (a few complications were introduced for heavier letters).

It was this relative simplicity that led to the production of stamps of two denominations: 10c and 20c. A widely circulated Royal Decree dated June 17, 1849, announced the issuance of stamps and established July 1 as their first day of use.

While yea-sayers and nay-sayers bickered, the Ministry of Public Works granted a contract to Jacques Wiener to oversee the production of both stamps. Wiener was the foremost medallist in the country and had considerable experience in metal engraving.

Furthermore, Wiener had already some involvement in the production of these two stamps, because in May 1848 he had requested on behalf of the ministry, and received from the English firm Perkins-Bacon a detailed statement of the cost of every step in the production of the two stamps, from die-making to gumming the sheets, and under different assumptions of quantities required. The price quote was addressed to the Ministry of Public Works, with a copy to Wiener.

Wiener received follow-up instructions from the ministry on Aug. 7, 1848, to proceed to London to purchase the recommended printing press for manufacturing postage stamps, and to make all other pertinent inquiries toward adding to his medal-making shop the capacity to print postage stamps. All this he did.

For the better part of a century Belgian, British and American philatelists had written that the dies and printing of the first issue of Belgium stamps were made by Wiener. It is well-known that the dies for the second issue of stamps of Belgium were made by Perkins-Bacon, and that the engraver was J.H. Robinson who worked for the widely famed firm, the printer of the Penny Black.

Then, sometime much later, a startling discovery was made. There appeared in the market a single die proof signed by H. Robinson, for a 40c red stamp of the same design as the 10c and 20c of July 1849. This find, entirely unique to this date, opened the subject of authorship of the engraving, and spawned an enigma, which still lies unresolved. Did Robinson engrave die proofs for the three stamps? And if not, who did?

Belgian students of the matter were forced to consider the possibility that the two dies for the 10c and 20c stamps were engraved in London by Robinson. It has been cogently argued that Wiener, having learned during his earlier visits to Perkins-Bacon and De La Rue of all the complexities involved in printing postage stamps, and of all the possible disasters that could occur — any one of which would certainly tarnish his reputation with no lesser a client than the king — decided subcontracting the work to the pioneers and experienced masters in London was a safer alternative. After all, Perkins-Bacon had by now printed hundreds of millions of stamps over a nine-year period, and Wiener had printed none.

No other documentation sheds light on the enigma. Only one small detail may be relevant: it was said by early philatelic writers that the reason a 40c Epaulettes stamp (as the first issue is commonly known) does not exist, is that King Leopold did not entirely approve of his image on the stamps. A 40c stamp would, therefore, wait three months until the second issue was ready in October 1848.

The dies for the 10c and 20c Epaulettes were created by either Wiener, of Brussels, or Robinson, of London. Perhaps some further documentation will surface in the future to clear the matter.

Be that as it may, one thing we know for sure is that when these two stamps began to circulate in Europe, there was nothing but admiration. The design soon became regarded as the most attractive of any stamp issued. In my opinion, the design is remarkably avant-garde. The artist did away with the frames; the image of the king appears to be floating in the center, unsupported, and contrasted by a subtle floral design tapestry, ornamental but barely noticed and not distracting. All attention remains firmly on the king.

Perhaps this artistic tour-de-force is the reason why these are among my favorite first-issue classic stamps. To say that the design was ahead of its time might be contentious, though one might consider that in the United States, to use one example, all stamps issued between 1847 and 1937 — 90 years — have heavy and sometimes massively ornate frames. The Presidential issues, known as the “Prexies” (Scott 803-834), are the first stamps issued by the United States that display their subjects without the support of pedestals, columns and adorned frames.

For the general collector of classic stamps the Epaulettes present two kinds of problems: margins and postmarks. The margins are tight because the cliches were placed on the plate too close to each other, and cutting the stamps apart must have been quite a headache for fastidious Belgian office workers. Stamps with ½ millimeter clear all around are considered to have full margins. The avid collector may look out for sheet-margin and sheet-corner positions that can have better margins and command premiums.

The second problem arises from the assiduousness with which Belgians canceled their stamps. The numeral cancellations, prevalent in the first issue, are usually too heavy, obliterating the effigy, especially when overinked. When the strikes are perfectly inked and accurately struck they are quite handsome.

The avid collector should look out for such strikes because, especially in combination with better than clear margins, they place the stamp in a premium category with values well beyond catalog values. There are 136 numeral cancellations, from “1” for Aerschot to “136” for Zelzaete. Amazingly, even the scarcest of these do not command great premiums.

Perhaps there is a rich field for study and fun in trying to obtain all the numeral cancellations without encountering punishing prices. For the 20c Epaulette, for instance, the range of values quoted in the Belgian specialized catalog, Catalogue Officiel Belge de Timbres Poste, is E65 for a stamp bearing the commonest cancellation and a mere E275 for a stamp with the rarest cancellation (which is number 93 for the town of Peer). Both problems, margins and cancels, can be converted into opportunities.

Looking further, the Epaulettes offer a good range of shades, due to various printings that became necessary. In the two examples of the 10c shown nearby, the stamp at left is of a dark brown shade (Scott 1c), while the stamp at right is of a reddish brown shade (Scott 1a), which has a used value of four to five times that of the normal stamp. Similar ratios apply between the values of the normal blue 20c (Scott 2) and the much scarcer milky blue (Scott 2a) and the outright rare greenish blue shades (Scott 2b).

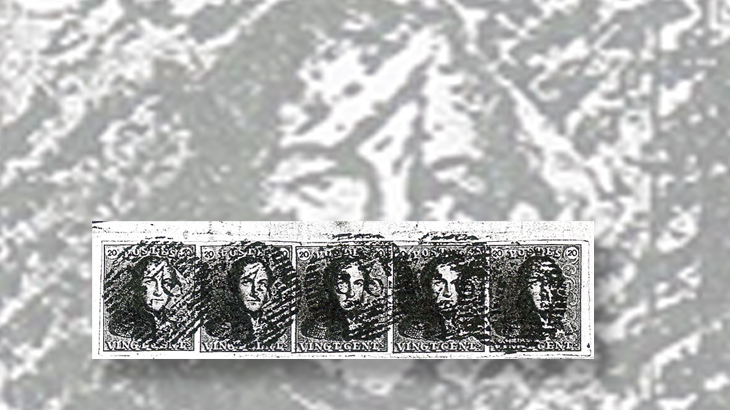

In closing, I wish to underline that there is much to gain by knowing more about the Epaulettes stamps. There are opportunities for fortuitous finds in their colors, in their marginal plate positions, in the range of numeral cancellations, misplaced watermarks, and in multiples, which are all very scarce.

And speaking of fortuitous, the strip of five 20c illustrated nearby is unique and is the largest recorded used multiple of this stamp. I found it looking through a miscellany of classic stamps at a Chicago show, which, in addition to this wonderful piece, included a large quantity each of the good, the bad, and the ugly.

All images are from the philatelic archive of Liane and Sergio Sismondo.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers