World Stamps

Covers tell the story of Great Britain’s Decimal Day, Feb. 15, 1971

By Lawrence D. Haber

Finally. It had taken more than a century of discussion to have reached this point, but following many studies and committee reports, the announcement from the British chancellor of the exchequer came in March 1966 that the United Kingdom would decimalize the pound.

The change would occur in five years’ time, on Feb. 15, 1971, soon to be known as Decimal Day, or D Day.

Since ancient times, Britain’s pound had been comprised of 20 shillings, each shilling being equal to 12 pence. A total of 240 pence made the British pound sterling. But, as of Feb. 15, 1971, the pound would be comprised of 100 new pence.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

For a time before calculators, the old system was a logical one: half a shilling is 6d, a quarter of a shilling is 3d, and a third is 4d.

After the announcement to decimalize, the first notable change that the stamp collector would see was the withdrawal and demonetization of the ½d stamp on July 31, 1969.

In decimal terms, ½d would be equivalent to less than a quarter of a new penny. There was no future for the old halfpenny, and both the coin and the stamps were withdrawn.

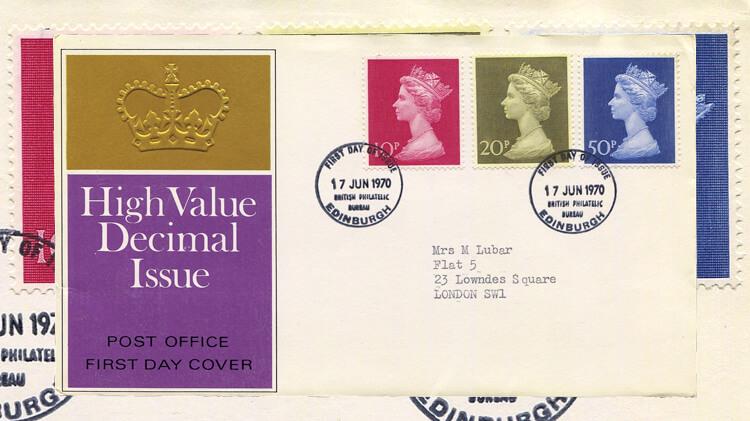

On June 17, 1970, the Post Office issued the first British decimal-currency postage stamps: three large-format Machins in denominations of 10p, 20p and 50p (Scott MH165-MH167).

These denominations could be used interchangeably with pre-decimal currency, because they were directly equivalent to 2sh, 4sh and 10sh. This would serve as an easy transitional step.

Today, we may have difficulty considering a 10p stamp a “high value.” But, in 1970, 2sh (10p) would have bought you a pint of beer in a London pub.

With the basic domestic first-class letter rate at 5d, there were limited uses for these stamps. Even overseas airmail rates would have fallen short; the rate to Australia, for example, was only 1sh9d.

Most of the pre-Decimal Day uses of these decimal stamps are seen on double-rated airmail letters sent overseas, or paying special services, such as registry, special delivery, or rates for heavy parcels.

As 1971 approached, all was ready for the full conversion to decimal. Up to this point, pre-decimal rates had prevailed. With Decimal Day on Feb. 15, a full set of new decimal Machins would be issued, and all the postage rates would shift to the new decimal rates.

The domestic price adjustment was dramatic. The basic first-class rate went from 5d (2p) to 3p, an effective increase of almost 50 percent. The second-class rate saw a similar increase. Both registry fees and express fees were increased by a third, from 3sh (15p) to 20p.

Internationally, the rate changes were minimal.

Taken altogether, there was much change and a great deal of potential confusion because the currency, rates, and stamps were all changing. It was critical for the Post Office to be performing at its best.

However, a complication occurred. On Jan. 20, 1971, a national postal strike was called. Postal workers walked off their jobs, and the postal system was brought to a virtual standstill. Less than a month to Decimal Day, and the Post Office was closed.

In an effort to keep the economy moving, the crown did not enforce its postal monopoly, the first time this happened since before the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603). Private carrier services sprung up across the nation.

Shown nearby is a Randall Postal Service Feb. 15, 1971, decimalization first-day cover.

Despite the strike, some small sub-offices, usually connected to a retail shop, remained open, and some of these processed mail to the extent that they could. From these, we can find FDCs with genuine Post Office cancels.

The strike was settled on Sunday, March 7, 1971, and postal workers returned to their jobs the next day, March 8.

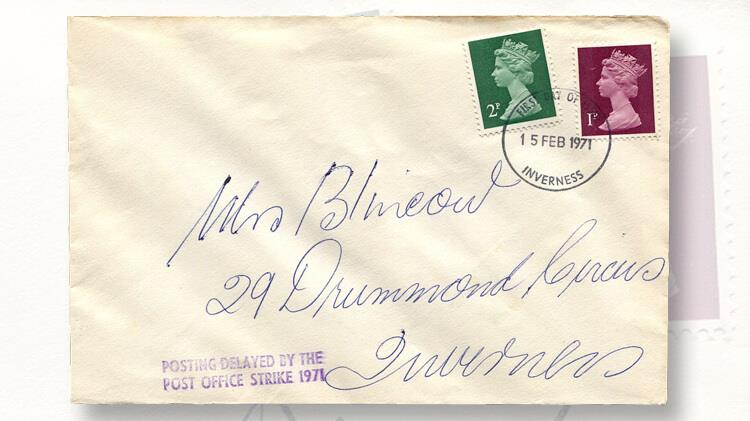

When the system came back to life, the stacks of FDCs that had been prepared prior to the strike being settled were processed, but with the addition of a special handstamp explaining the delay.

Following the strike, the postal system quickly returned to normal, but with new decimal rates and stamps that, for the near term, would coexist with the old pre-decimals.

Rates could be met entirely with new decimal stamps or with sufficient pre-decimal stamps or a combination of the two.

Occasionally, the math associated with calculating the full rate on a cover could be a bit of a challenge.

One such example is the domestic recorded-delivery cover shown nearby. The recorded delivery fee was 4p, and the letter was sent second class at 2½p for a total of 6½p. The cover is franked with the 4d Christmas stamp issued in 1970 (Scott 645) now worth 1½p, plus two ½p Machins and a new 4p Machin bringing the franking to the 6½p total required.

What is remarkable is that overall there appears to have been little confusion with this change. The British public seems to have made the transition with little difficulty, though, of course, there were bound to be some issues.

The decimal transition came to a close on Feb. 29, 1972, 12 and one-half months after Decimal Day. Thereafter, all pre-decimal stamps were demonetized and would no longer be honored.

However, on occasion they did pop up, some shortly after demonetization and some not so soon afterwards.

Even today, the occasional pre-decimal stamp might pass through the mail, but all considered, the transition was remarkably smooth. The United Kingdom had cast off an ancient system for its currency and has yet to look back in regret.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers