World Stamps

Postal reform in France met with intense opposition: Unveiling Classic Stamps

By Sergio Sismondo

Today we cross the Channel once again. Last month (Linn’s, Feb. 15), we went from London to Brussels to find out why it took almost 10 years for Belgians to decide to institute a postal reform and to issue stamps to prepay postage, the way the British had done in 1840. Today I want to take you to Paris to study the same question as it applies to France.

France had the third largest number of posted letters in the world. In 1844, for example, 111 million letters were posted; in 1846, 120 million letters were posted. The annual growth of the volume of mail in France was about 4.5 percent per annum through the 1840s. Rural letters accounted for about 25 percent of the total and were subsidized by the treasury, paying only 10 centimes for 7.5 grams weight.

It had been clearly established that such letters were paying below the cost of handling. Other letters were taxed by weight and by distance, the minimum being 20 centimes, and rapidly increasing to 1.20 francs for 7.5-gram letters to the 10th arrondissement of distance. The bulk of letters posted were contributing positively to the treasury.

Connect with Linn's Stamp News:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Keep up with us on Instagram

French leaders, political and not, discussed from time to time the matter of adopting parts of the “English Postal Reform.” As we have seen in other countries (for example, Brazil and Belgium), there were strong proponents. The argument was the same: lower the overall charge, and private individuals and businesses will increase their use of the system, the unit cost of handling and delivering letters and packages will be reduced, and businesses will grow on the basis not only of the expansion of their clientele, but also of other possibilities such as broader advertising and product delivery.

Among the enthusiasts was Felix de Saint Priest, member of the Legislative Assembly, who, being fully aware of the success of the English postal reform, and noting eight years of inaction in his own country, undertook on his own account to draft a bill outlining all the aspects of a comprehensive postal reform.

Saint Priest circulated a draft to friends on May 4, 1848, and presented the bill to members of the Legislative Assembly on May 19th for information and discussion. The principal elements of the reform were as follows: (i) To lower postage rates so as to encourage the growth of the postal system; (ii) To institute the prepayment of postage so as to simplify the collection procedures which were as costly as they were vexatious; (iii) To eliminate the distance charge, creating a sole national postal schedule of rates; (iv) To reduce or eliminate widespread fraud that occurred regarding contract transportation charges.

Meanwhile, a new postmaster general was appointed, Etienne Arago, who championed the reform. He found little to disagree with in Saint Priest’s bill, and convinced the country’s leaders that the whole proposal, lock, stock and barrel, was an excellent modernizing idea that would, with little doubt, lead to growth for many or all sectors of the economy. The postmaster general added his own interesting personal notion, suggesting that reduced postal rates would, by promoting the writing of letters, increase the level of education of the population-at-large.

Arago oversaw the redaction of the government’s own bill, which eventually replaced Saint Priest’s bill when tabled at the legislature.

The government let it be known that it was in favor, circulated some facts and figures to support its case, and scheduled a full legislative debate for Aug. 24, 1848. Reading the transcript of that session, which must have been very long indeed (8 a.m. to 6 p.m.), affords a fascinating window on the mindset of the people’s representatives at the time.

On the one hand, the legislators show by their critiques to possess sharp minds for quantitative details of public finance and management; and, in general, demonstrate rhetorical capacity almost hard to believe. On the other hand are the counterarguments, many and varied, which the government side had to either take into account or rule out.

Some of the most interesting arguments are intensely political, in some ways throwbacks to the days of the revolution. Various members expressed strong negative opinions because reducing postage rates would be a subsidy to the rich, who wrote the most letters and sent the most packages, while no appreciable benefit accrued to the poor from the proposed reform.

Equally, eliminating the distance surcharges, a move which was intended to strengthen the unity of the nation in a multiplicity of ways, was opposed because it too represented a subsidy from the treasury to the rich, and that was not acceptable. In that the postal reform was intended to benefit the growth of business, while probably reducing public revenues, the entire law seemed to be a design to further impoverish the common folk while enriching the pockets of business owners.

One member ranted at length to demonstrate that the “English Postal Reform of 1840” was shrouded in fraud by the public purse, as the treasury lost enormous amounts of money, and they lied about that, while the merchants enriched their accounts from the reduced tariffs.

Such statements led to the reading in all its details of a report of the government’s finance committee, which was reassuring regarding the proposed reform’s impact on the national treasury.

Another member wanted to change the basic weight of a letter to 10 grams, from 7.5 grams, because “everyone knows what ten grams is, while no one can intuitively say what 7.5 grams is like.”

The legislature president’s gavel closed the session with the clock striking 6 p.m., having craftily received majority support for the bill, and having ruled all proposed amendments to be either not based on sufficient knowledge of the postal system, or to be irrelevant to the issues at hand. The law was basically accepted as written.

It specified that letters of weight 7.5 grams or less would be charged 20 centimes regardless of destination (within France and Algeria); letters of weight between 7.5 grams and 15 grams would be charged 40 centimes, and letters between 15 grams and 100 grams would be charged 1 franc.

For items above 100 grams, the increments would be 1fr for each 100 grams, or fraction thereof. Thus, for instance, a small packet or document of weight 340 grams would be charged 4fr.

Printing became the next priority. The rate schedule adopted indicated stamps of three denominations were needed: 20 centimes, 40c, and 1fr. Always the good business people, Perkins-Bacon of London offered to print French postage stamps for 1fr for each sheet of 240 stamps. But the offer was turned down, and instructions came down to print the stamps at the French Mint.

No doubt the decision was influenced by the printing experience acquired by the mint in printing paper money, and the presence of accomplished masters of the trade already in place. The artist and engraver was to be Jacques-Jean Barre, and the printer Anatole Auguste Hulot, both already employed by the mint. If Barre and Hulot were not already famous before the advent of France’s postage stamps, they were destined to become so very soon after.

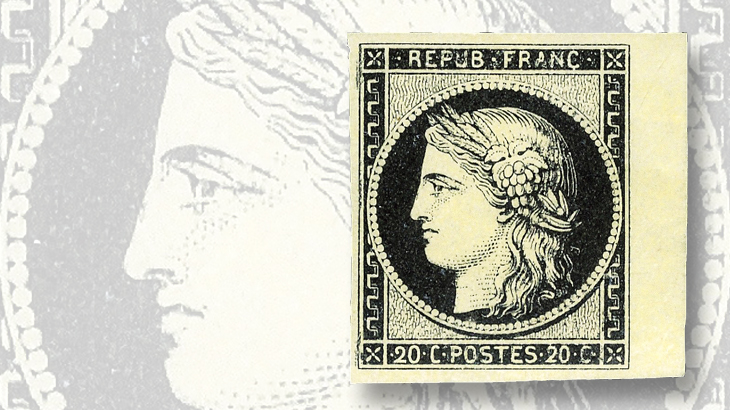

The minister had said the stamps would bear a miniature “Face of the Republic.” The president had for some time referred to the desired image as the “Face of Liberty.” But differences melted down when Barre’s masterful design was presented, with the austere but happy face, crowned with wheat sheaves, olives and grapes.

It is said that one cabinet member noted the image properly represented all that was desired: “the Republic, Liberty, and most important, a positive augur for the coming harvest.”

The cabinet approved. It was settled without argument that the stamps would bear the image of the Greek deity of plenty, Demeter, which became known to philatelists as Ceres, its Latin equivalent, and its design would be just as proposed by Barre.

We will discuss these stamps in greater detail in the April 18 issue of Linn’s monthly.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers