World Stamps

Taking things at face value can be confusing with Cuba’s dual currency

By Peter Yaghmaie

A dual currency system is a financial system in which two different sets of local currencies are used for financial transactions. Cuba remains one of the few, if not the only, country with such a system.

The Cuban peso, also known as the moneda nacional (national coin or currency), has existed since 1857, when it replaced the Spanish colonial real.

The Cuban peso’s ISO 4217 currency code, a designation established by the International Organization for Standardization in Geneva, Switzerland, and used in global banking and currency, is CUP. (The United States dollar is USD.)

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Following the end of the Cold War, a second currency was introduced around 1994: the Cuban convertible peso; its ISO 4217 code is CUC.

The CUC is valued on par with the USD. Around the same time, the U.S. dollar also was designated as legal tender in Cuba and remained so until the year 2004, when it was withdrawn from circulation.

The CUP is valued at a fixed exchange rate of 25 CUP = 1 USD. Most Cuban workers are paid their basic salaries in the CUP; however, some bonuses are paid in the CUC.

The CUC is used for the purchase of luxury and imported goods, and for products and services aimed toward tourists visiting the country. State-run shops usually accept both the CUC and the CUP currencies.

CUC coins have an octagonal frameline within their outer circular rim, while CUP coins are fully round.

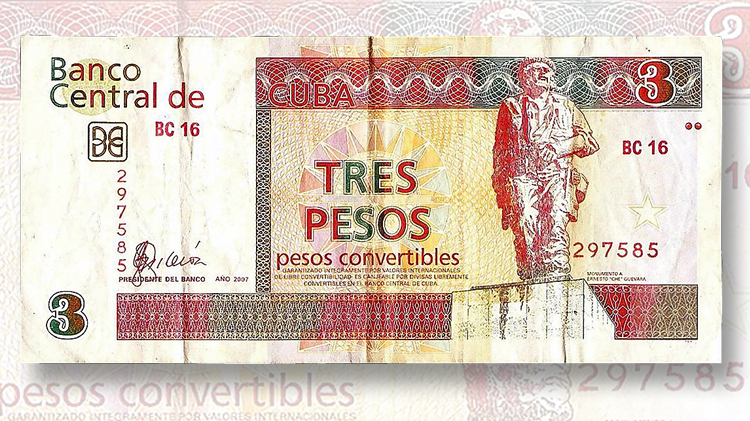

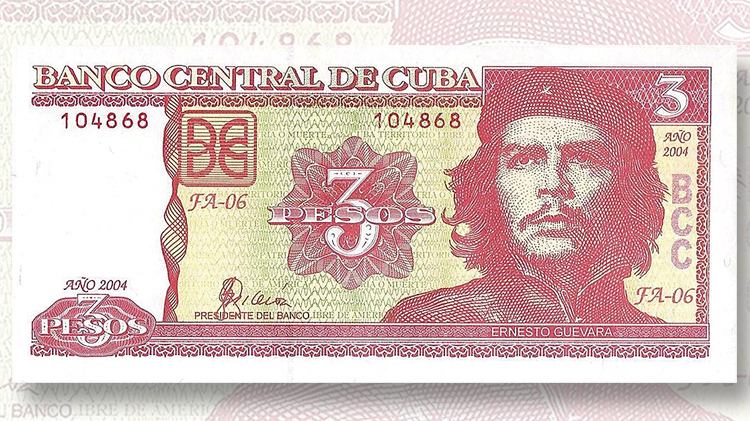

The CUC banknotes feature historic Cuban monuments whereas CUP banknotes feature famous Cuban personalities.

Besides the confusion in financial transactions that can arise from having a different set of coins and banknotes for each currency, Cuba’s dual currency system also has created some challenges for stamp collectors.

The difficulty arises from the fact that Cuba’s stamp emissions and much of its postal stationery, with only a few exceptions, continue to be denominated and sold locally in the CUP.

In conversations with various Cuban philatelists over the years, the author was told that only a handful of postal issues were sold solely in denominations of the Cuban convertible peso (CUC) rather than in the Cuban peso (CUP). One such issue is rumored to be Scott 3681A-3681C and 3682-3687, a series of nine small stamps featuring orchids and issued between November 1995 and June 1996.

These stamp collectors also mentioned that some postal stationery, such as prepaid postal cards featuring Ernesto “Che” Guevara, also are sold only in the CUC.

The challenge for philatelists arises from the fact that the values of Cuban stamp issues in the international stamp catalogs and markets since the introduction of the dual currency are based on a multiple of the CUC (the stronger currency that most issues are not denominated in) instead of the CUP (the weaker currency that almost all stamp issues are denominated in).

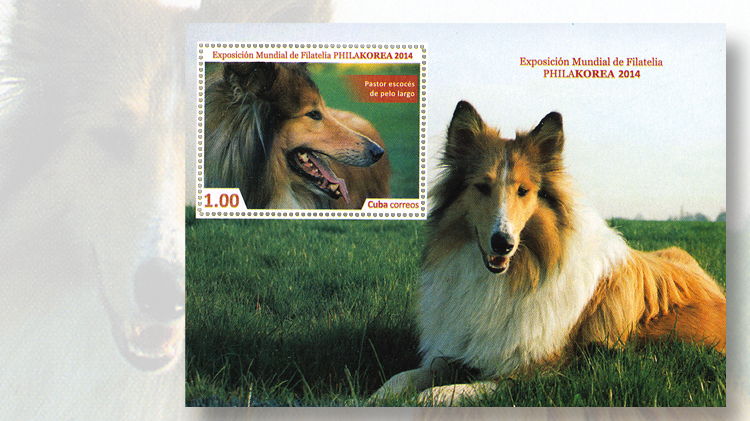

The result is catalog values that can be 40 or more times the face value of the issues of the last two decades of stamps of Cuba. A typical Cuban souvenir sheet of recent decades, such as Scott 5554, issued in 2015 to mark the international exhibition Philakorea 2014, has a face value of 1 CUP, which is equal to about only 4¢.

In contrast, such an item is valued at about $2 in the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue and at about €2 in the German-language Michel catalog; that is, approximately 50 to 57 times face value.

Likewise, a typical Cuban set of four to six stamps of recent years has a face value between 2.65 CUP and 3.15 CUP and has a catalog value of approximately $4.25 to $6.25, or some 40 to 50 times face value.

One consideration that may partially justify this gaping discrepancy is that local access to complete sets and mini sheets for collectors in Cuba appears to be regulated.

Local stamp collectors report that full sets are not usually available at post offices, and that most recent/new-issue philatelic material is offered in limited quantities by subscription to members of the national Cuban Philatelic Federation (Federacion Filatelica Cubana, also known as the FFC).

It also should be noted that, according to XE, an Internet-based currency information and exchange company (XE.com), the Cuban government imposes a 10 percent tax on converting U.S. dollars to the CUC, or vice-versa (except for exports). This tax was introduced on Nov. 14, 2004, and is not applied to other foreign currencies.

Nevertheless, the difference between face value and catalog and market values for the vast majority of Cuba’s postal issues is still staggering, given that the majority of recent and new issues of most other countries in the world are generally valued at two to three times face value: a factor that is far smaller than the large multiples of face value at which Cuban issues are valued.

Although the stamps of Cuba offer an attractive mix of topical issues, often featuring flora, fauna, and transport, as well as political subjects, the ramifications of the dual currency system might cause some collectors to rethink the feasibility of collecting Cuba.

Worldwide financial news sources reported in late January 2014 that Cuban newspapers had announced that President Raul Castro’s government was taking steps to unify the two currencies, possibly consolidating them into a new peso valued at an exchange rate somewhere between that of the CUP and the CUC.

However, there do not seem to be significant developments on this front. This proposed currency reform would be a welcome development that would bring catalog and market prices closer to the face values of Cuba’s postal issues since 1994.

Special note: According to the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the U.S. Treasury Dept., stamps of Cuba issued since the embargo of Feb. 7, 1962, may be imported and resold if the stamps are in used condition, and imported for personal use only if they are in mint condition.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers