World Stamps

The case of Saudi Arabia Scott L66B: 50 overprinted stamps or 100?

Middle East Stamps - By Ghassan Riachi

In philately, it is imperative to know the number of stamps issued to determine rarity and help in pricing. This is true regardless of which area one collects.

The stamps of Saudi Arabia are no different. However, with many of its early overprinted stamps the quantities are unknown because no records were kept.

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Often times, by plating (reconstructing a stamp pane by collecting blocks and individual stamps representing various positions) it is possible to determine the number of examples issued of a particular stamp. This is the case for one of Saudi Arabia’s stamps.

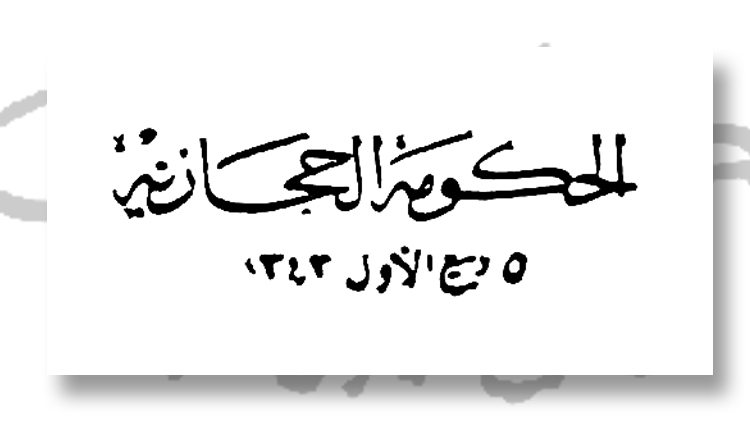

Today, Hejaz is part of Saudi Arabia. But between 1916 and 1925, it was a sovereign nation. In 1925, Hejaz issued numerous stamps with the same Arabic overprint that translates to “The Hejaz Government, October 4, 1924.” This date is important; it represents the time when King Ali ibn Hussein ascended to the throne of Hejaz. The 1924 overprint from Hejaz is below.

The overprint was applied to Hejaz stamps in different formats and colors. It was written as a large three-line, a small three-line, and a two-line overprint, in addition to others. In this column, I refer to the two-line format as the Jeddah two-line overprint.

The overprinted Hejaz stamp listed in the 2017 Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue as L66B is the subject of this column.

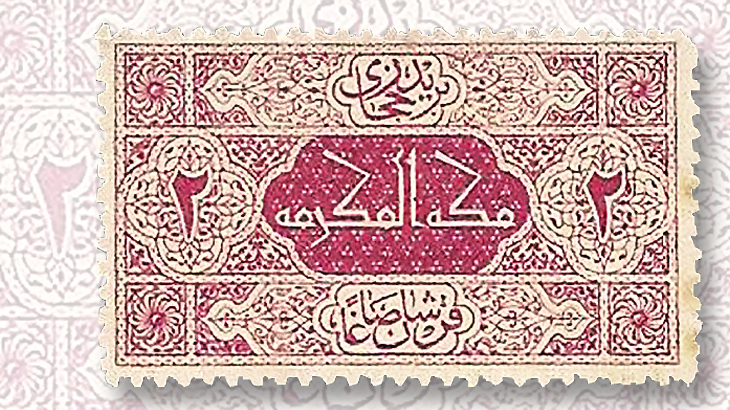

The base stamp is the 2-piaster high denomination (Scott L13) of the Hejaz set of six issued in 1917 (L8-L13). You'll see the 2-piaster stamp below.

The Survey of Egypt in Cairo printed these stamps on unwatermarked paper. They are serrate roulette 13.

All of the denominations, which ranged from 1 para to 2 pi (1 pi is equivalent to 40p), were issued in sheets of 50, formatted 10 rows by five columns.

Scott L66B is Scott L13 with an inverted Jeddah two-line overprint in blue. The overprint is upright when the large line is above the small line, otherwise the overprint is inverted.

Collectors are cautioned about forgeries of this stamp, including what appears to be the normal (upright) overprint, which does not exist.

The Jeddah two-line overprint plate had 50 cliches, 10 rows by five columns. The cliches are numbered as positions 1 through 50.

A cliche is an individual unit consisting of the design of a single stamp. Multiple cliches are combined to make a complete printing plate.

In the grade of very fine, Scott gives a retail value of $1,900 in italics for L66B. Scott values this stamp only in unused condition.

I have seen examples of this stamp in mint never-hinged condition, hinged, and unused with no gum. I have not seen it used on or off paper, even canceled-to-order, or on any kind of cover.

For years, a controversy has surrounded L66B. Specialists, collectors, and stamp dealers in Saudi Arabian philately have debated whether or not one sheet of 50 stamps or two sheets were issued.

Some of them believed that two complete sheets of 50 stamps each had been issued simply because of duplication of overprint positions.

Other specialists, collectors, and dealers have wondered if there is only one sheet of 50 stamps, and, if there is only one sheet, then why can’t we find any of the stamps with overprints from positions 26 to 50?

In 1988, this enigma resurfaced when F. C. Benedict wrote about L66B in the Arabian Philatelic Association’s publication Random Notes.

Benedict had a theory about the quantity issued, but was unsure if overprint positions 26 to 50 existed. He even asked readers to contact him if they owned this stamp and give him the plate position numbers of the overprints on their examples.

So what is going on? Before I attempt to solve this mystery and give the actual quantity issued of L66B, some background information is needed to understand my findings.

When I first started collecting the stamps of Saudi Arabia, the only major reference available to me was The Postal Issues of Hejaz, Jeddah and Nejd by D. F. Warin, published in 1927.

Scott L66B was not listed in Warin’s book. However, it was listed in a price list booklet called The Postage Stamps of The Hejaz, Jeddah and Nejd, also by Warin. This booklet did not price L66B, but it did give the quantity issued of this stamp as 50.

When I was collecting in the 1970s, I did not own this booklet or have access to it.

Because L66B was not listed in Warin’s original 1927 book, and because the few examples I had possessed of what supposedly were L66B had fake overprints, I entertained doubts as to the stamp’s existence.

Two events in the early 1980s erased those doubts. First, I obtained the 1981 Scott Standard catalog and found that L66B was listed. Second, John Wilson published The Hejaz — a History in Stamps in 1982. In this book, Wilson reiterated the existence of L66B and stated that only “50 copies” were known.

As noted earlier, the Jeddah two-line overprint plate includes 50 cliches, each slightly different from one another, which permits plating. Each sheet of the basic stamps had 50 stamps, and each stamp received one single overprint.

Therefore, if one sheet of 50 stamps of L66B is correct, then every L66B stamp must have a different overprint position for a total of 50 overprinted stamps.

Because both Scott and Wilson listed L66B, I started looking for a genuine example of this rarity for myself. Over the years, I was able to secure a few examples. One can be seen below.

In addition, I have always enjoyed studying overprints in auction catalogs, especially if the illustrations were clear enough. I came across a few auction catalogs that both listed and illustrated examples of L66B. This enabled me to study these illustrations and draw some conclusions.

An important auction catalog by Habsburg, Feldman S. A. in November 1987 listed the sale of Dr. A. (Alex) Kaczmarczyk’s fabulous collection of Saudi Arabia. Two lots of L66B were offered.

The auction catalog descriptions of both lots, 30521 and 30522, are worth repeating:

“30521 ** [mint never hinged] 2pi claret with BLUE overprint inverted, nh bottom sheet marginal block of 10, showing plate No. 19 & cylinder no. N-10-A, negligible toning, v.fine & a unique plate block, only one sheets (sic) of 50 printed (SG £15000+)”

“30522 * [lightly hinged] 2pi claret BLUE overprint inverted (pos. 6), lh marginal single, fine & a rare stamp, only one sheet of 50 printed (SG£1500)”

According to the auction house’s prices realized list, both lots were sold. The block of the 10, the first lot, realized 22,000 Swiss francs, and the second lot, the single with margins, sold for 2,200fr.

The color pictures of these two lots in the auction catalog were clear enough to permit the plating of the overprints on the basic 2pi stamps and provide the establishment of the overprints’ positions in the plate.

Because Kaczmarczyk was a renowned expert in this field, I accepted this bottom block of 10 to be genuine. The positions of the overprints on the block were 1 through 10.

Also, because Kaczmarczyk had two stamps with overprint position 6, and because I already had a stamp with overprint position 1, I was astounded that there could be such a duplication of overprint positions.

Over the years, I have been puzzled by the fact that I kept coming across examples of L66B that have other duplications of the overprint positions. I also have seen two stamps with overprint position 22. The question that begs to be asked is: “Was there in fact more than one sheet of L66B?”

What makes this question difficult to address is that all the genuine examples of L66B that I have examined have overprints from the top half of the sheet, positions 1 through 25.

I have seen nine stamps with overprints supposedly from the bottom half of the sheet. The overprint positions are 28, 32, 35, 37, 39, 41, 42, 45, and 50.

Upon inspection, however, I discovered that every single one of them is a laser forgery. It is odd that none of the stamps can be found with a genuine overprint from positions 26 through 50 of the overprint plate.

Could there be two-half sheets of 25 stamps each making a complete sheet of 50?

The matter remained in this state of affairs until by luck a left-margin block of four of L66B surfaced that sheds light on the quantity issued. (It should be noted that this discovery block of four is heavily creased horizontally between the upper and the lower horizontal pairs. The crease is also clearly seen in the margin). The block of four is pictured below.

I studied this block of four several times, and have confirmed the following plate positions. The results were surprising.

The plate positions of the overprints in this block normally should have been 24 and 25 for the stamps in the upper left and upper right, respectively, and 29 and 30 for the lower two stamps.

But while the upper two stamps are 24 and 25, the lower two are 4 and 5.

So what is going on?

The truth began to come out.

There is indeed only one sheet, but it was folded horizontally in the middle, back to back, and in this state was put into the press twice in such a way that the sheet received inverted overprints, once for each half of the sheet in its folded state.

As a result, the top half of the sheet received the overprints from positions 1 through 25, and the bottom half of the sheet received the same overprint positions.

In other words, there are duplicate overprinted positions on the two half sheets, making a total of 50 stamps overprinted. Stamps with overprint plate positions 26 through 50 do not exist.

I believe I have solved this mystery, and I encourage those who are interested to find one of these rare 50 stamps.

Of course, some collectors may still have questions. For example, why at the time of overprinting was this L13 sheet folded, and why didn’t the printer unfold the sheet? Also, was the printer aware that the overprint on this sheet was inverted?

To address these questions, we need to look at the history of Hejaz.

The Kingdom of Hejaz, located in the Arabian Peninsula on the Red Sea, contained the two holiest cities in Islam, Mecca and Medina, in addition to the seaport city of Jeddah. The kingdom’s neighbor on the west was the Sultanate of Nejd, with the capital city of Riyadh.

In 1924, war broke out between the two nations. At that time, Sultan Ibn Saud, the great desert warrior, ruled Nejd, and King Ali ibn Hussein ruled Hejaz.

King Ali felt that if the holy city of Mecca was attacked he would not be able to protect it. Thus, on Oct. 13, 1924, the king decided to leave Mecca and move his government to Jeddah.

In addition to gathering other items, the king ordered his officials to gather up as many stamps from Mecca as they could to take with them to Jeddah. This stock of stamps included current and older Hejaz stamps.

In haste, the king’s officials gathered up as many of these stamps as they could carry, most likely not taking any care in handling them or packing them neatly and properly.

What exacerbated the condition of some of these stamps is that they were probably placed on the backs of camels and transported from Mecca to Jeddah.

During handling and transporting, some of the stamps became wrinkled, folded, stuck together from moisture, torn, or damaged in one way or another.

In Jeddah, King Ali commanded the overprinting of the stock of stamps.

Overprinting was important for two reasons: to invalidate the stamps that had been left behind in Mecca and had fallen into the hands of the Nejdis; and to raise funds to help the king in his war effort through the sale of the overprinted stamps.

However, the government printing press was in Mecca, and apparently the king did not have skilled people in Jeddah with the right expertise to overprint the stamps. The king’s officials had to seek out a local Jeddah print shop to perform the task.

Unfortunately, the job of overprinting the stamps was not profitable enough for the print shop owner who was chosen to carry out the task. As a result, the owner did not want to be bothered with this work and delegated the task of overprinting to his workers.

These workers were not only unskilled in overprinting stamps, many of them were illiterate as well, and they were left unsupervised. The condition of the stamps made matters worse.

The workers tried to separate the stamps that were stuck together by applying moisture. In doing so, some stamps were stained, some endured face and gum damage, and others were destroyed.

The stamps that could not be freed from each other were overprinted the way they were on the front and on the back.

The workers were confused by the task. Some of them couldn’t tell the difference from the tops or bottoms of the stamps. So they loaded the stamps into the printing press without any knowledge of the correct way to place the stamps.

In the resulting chaos, stamps received inverted overprints, double overprints (both upright or both inverted), and double overprints with one inverted on the face.

Other stamps were overprinted on the gummed side.

Some stamps received up to five overprints, some of which are partial.

Also, while some stamps in a sheet or partial sheet were overprinted, others in the same sheet or partial sheet were not.

In addition, while an upright overprint was intended, some stamps received vertical overprints reading either up or down. Some stamps received the wrong overprint.

Many overprint varieties were created by these workers.

It is easy to understand that when a philatelic task of this magnitude is given to illiterate workers who are unfamiliar with the methodology of overprinting stamps, there potentially can be a multitude of mistakes and overprint varieties.

These varieties were created because this task was hastily performed without any real quality control in place.

As for the sheet of L66B, it is clear that the workers didn’t know or care that the overprint was applied inverted to the basic stamps.

It is also clear that the workers noticed that the sheet was folded in the middle. Rather than bothering to unfold the sheet, they overprinted half of the sheet and then just flipped the folded sheet over and added the overprint to the stamps of the backside. Thus, the L66B sheet was created with only the first 25 cliches being printed on it.

It is amazing how political and social conditions can play a role in creating major philatelic rarities.

Scott L66B is an excellent example of how knowing history is essential to understanding how a stamp came into existence.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers