World Stamps

Mexico’s ‘Little Mules’ have carried stamp collectors a long way

Spotlight on Philately — By Fred Baumann

Writing this column has disabused me of any illusion that I know about stamps, because every series Linn’s readers have suggested for my Spotlight column featuring great stamp sets of the world has been one-of-a-kind.

They all have ink and gum, perforations, and watermarks — attributes shared by most postage stamps for 177 years — but each series has its own perspective, attributes, delights, and challenges. Each is its own kingdom in miniature.

This month brings us late 19th-century definitives hailed by Linn’s reader Eric Stovner as “a series that I have found quite fascinating and enjoyable: Mexico’s Mail Transportation issue, in use from 1895 to 1899 (Scott 242-291), and fondly known as the ‘Mulitas’ series after the little mules on some of the stamps.”

Connect with Linn’s Stamp News:

Sign up for our newsletter

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

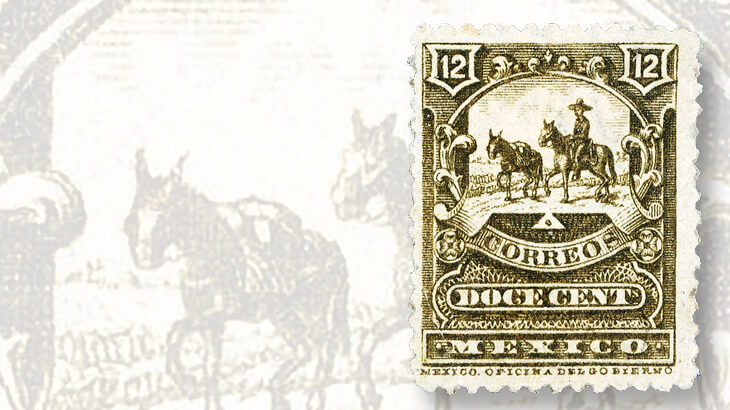

The design of the 12-centavo olive-brown stamp (Scott 262), picturing a mounted mail carrier and his sure-footed pack mule, best displays a little mule. This image, the first in the slideshow above, along with many others shown in this column, was generously made available to Linn’s by Bubba Bland of Rancho Santa Margarita, Calif. Bland is president of the Mexico-Elmhurst Philatelic Society International (MEPSI).

Stovner added, “The stamps depict every mode of transporting the mail at that time: by foot; by mule or horse; by stagecoach; and by train (which stamp design also faintly shows a boat in the background). The anomalous stamp design in the series depicts the Statue of Cuauhtemoc in Mexico City.”

According to Karl H. Schimmer’s masterful study, 1895-1898 Mail Transportation Issue of Mexico, this depiction of the last Aztec king was used on the 5c stamps “supposedly because the Aztecs already had Mail Runners” carrying messages for the emperor during the Pre-Columbian era.

“There are references available which indicate the mode of transportation available to each Mexico town,” Stovner concludes, “and I find it fun to find stamps and covers that were transported by foot, mule, stagecoach, train, boat, or combinations thereof, matching the theme on the stamps.”

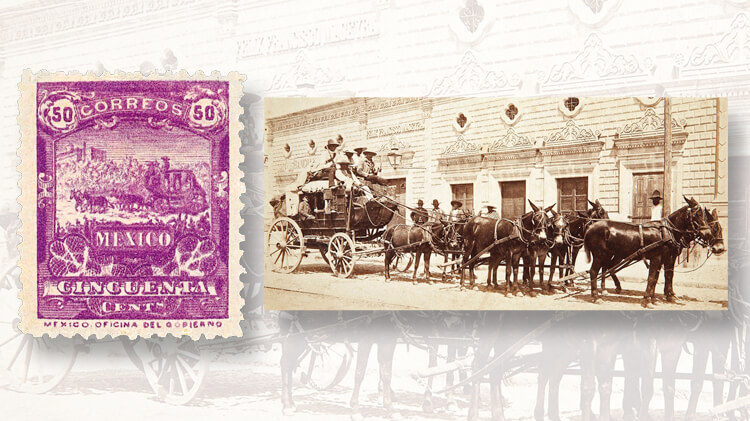

The stamp in the series that pictures multiple mules is the same one that depicts the stagecoach. I was surprised when I first looked closely at Bland’s 50c purple stamp (Scott 265), with five tiny draft animals pulling the coach at a seemingly ambling pace, and three men holding the traces sitting in the driver’s box and crowded onto the roof.

Then I found the photograph, circa 1890s, of a “Mule-Drawn Mud Wagon Stagecoach with Armed Guards, Chihuahua, Mexico,” sold in a May 2010 auction of historical memorabilia by Heritage Auctions of Dallas, Texas.

The stagecoach shown in the photograph has seven mules (with two smaller ones just ahead of the coach and another in the middle of the central threesome). Apparently transporting money from a bank in a padlocked strongbox next to the driver, the stagecoach carries four armed guards and two visible male passengers. Like the stagecoach on the stamp, instead of horsepower this one apparently relied on abundant firepower to cope with would-be bandits.

Reduced to philatelic fundamentals, the Mulitas seem simple. Scott catalog listings for the basic issue come to just 20 inches. You’ll find a brief but readable and nicely illustrated overview in the “Mail Transportation Issue” installment in the “Overlooked” series of introductory monographs available for free online via the website of MEPSI. The topics named “Overlooked” are from a series of emails sent by Blad to members of the society and to clients of his eBay business.

Those seeking more detail might appreciate Nicholas Follansbee’s helpful subdivision of the Mail Transportation stamps by watermark into five distinct issues, but it still fills little more than eight pages in his well-regarded 2015 Catalogue of the Stamps of Mexico 1856-1910.

Last and arguably most important as a reference might still be Schimmer’s 1895-1898 Mail Transportation Issue of Mexico, published in a limited 40-page edition in 1972. In 1995, the book was republished with enhanced images, some key items in color and an expanded 100-page format for the centennial of these stamps.

Only 75 spiral-bound copies were printed, but MEPSI now offers downloadable digital copies to its members for $10, available from its library and digital publications department. It is a remarkable publication — quirky, insightful, and jam-packed with indispensable detail that only a devotee with decades of experience as a collector, exhibitor, and MEPSI expert committee chairman could share.

The good news for newcomers to the Mulitas is that they lack the amazing array of complexity confronting those who pursue the prior four decades of Mexico’s various Hidalgo and Juarez issues, with their bewildering array of types, paper varieties, errors, shades, remainders, postal forgeries, cancellations, and, above all, seemingly endless district overprints.

Catalog numbers for these early issues of Mexico are far outnumbered by minor suffixed varieties in Scott, and wise beginners will correctly sense that these are but a foretaste of the complexity and very high catalog values ahead.

By contrast, the generally affordable Mulitas might seem like child’s play. As Stovner observes, there are only five designs in the entire series.

Shown in the third image above, from left to right, are stamps bearing the other three designs of the 1895-99 Mail Transportation issue: a 3c orange picturing a rural letter carrier with his staff and a small dog (Scott 259); a 5c blue depicting the monument of Cuauhtemoc, the last Aztec monarch, on Mexico City’s famous Paseo de la Reforma (283); and a 1-peso brown showing a mail train (289).

The first set of 13 denominations (1c, 2c, 3c, 4c, 5c, 10c, 12c, 15c, 20c, 50c, 1p, 5p, and 10p; Scott 242-256) in these five designs was issued in 1895 on paper with a “CORREOS E U M” watermark, Scott Watermark 152. (Correos translates to “post,” and the letters in the watermark are the initials for Estados Unidos Mexicanos, which translates to United Mexican States).

This watermark was configured with the intention of one large single-line letter appearing on each stamp in every horizontal row of 10 in the sheets of 100. However, a column of stamps on these sheets did not receive watermarks because the watermarks did not fit the sheet size.

Seasoned collectors can identify these by the vertical grain of the paper, as detailed in the Scott catalog footnote following Scott 291.

All these stamps were regular or pin-perforated gauge 12 on wove or laid paper.

Scott and Follansbee differ on the precise gauge and distribution of other perforations on the stamps. A curious Scott footnote lists only the 4c orange Mounted Courier with Pack Mule as existing perforated gauge 11, though it provides no listing, nor any values. Follansbee lists 10 stamps and lists and values all but the 1c green both on porous, wove paper and on thin, hard paper.

Where Scott lists six denominations as perforated gauge 6 (Scott 242b-249a), and nine as perforated gauge 12 by 6, perf 6 by 12, and compound or irregular (242c-253b), Follansbee lists seven perforated gauge 5½, and 10 that are perforated 12 by 6, perf 6 by 12, and compound or irregular, all on thin, hard paper.

Another Scott catalog footnote states that “irregular perfs” refer to Mulitas that “have both perf 6 and 12, or perf 5½ and 11, on one or more sides of the stamp.”

Follansbee notes that forged perforations are common, adding that the more expensive stamps require certificates of authenticity from reliable expertizers.

This is as good a juncture as any to issue a caveat on condition concerning these 122-year-old stamps. Mexico was well on its way to having the modern mail service that it enjoys today when the Mulitas were issued, and they are attractive designs.

That said, Mexico lacked both the amenities and the technological sophistication of the world’s best security printers when these government-printed stamps were issued.

Collectors who have never looked upon anything but well-centered, post–World War II stamps from the former colonial powers of Europe might be a bit taken aback at the rough-and-ready look of some of their Mexican contemporaries.

To ease the culture shock, shown in the fourth image in the slideshow above are 21 fairly common used Mulitas from a group of 23 that were sold four months ago by Oquist Stamps of Monrovia, Md., for about $17. Though they illustrate a wide range of shades and often poor perforation, these 21 are above average for the series.

The Mulitas had an unusual origin, as well. In Schimmer’s telling of it, the planned new issues were revealed in a March 24, 1895, Mexico City newspaper report identifying four designs as winners of a “competition held by the Ministry of Communication for the best stamp design for a new stamp issue.” The winner was Gilbert Lomeli of Queretaro. (As noted previously, a fifth design for a 5c stamp picturing Cuauhtemoc was later added to the lineup.)

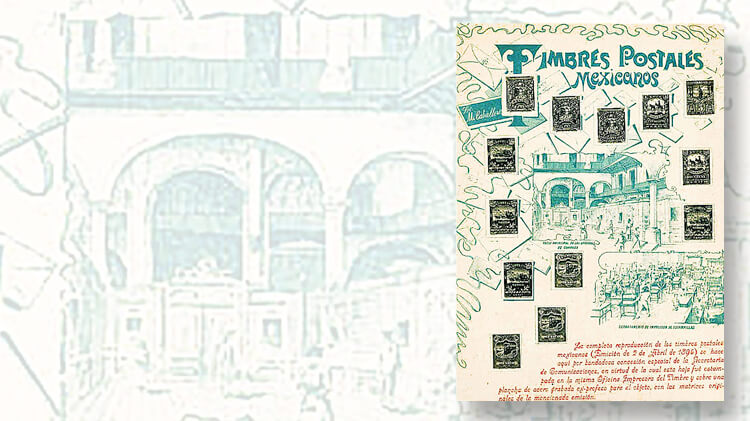

Pictured in the fifth image above is one of philately’s strangest proof items, a page from Manuel Caballero’s Almanaque Mexicano de Arte y Letras of December 1895, with all 13 of the new stamps printed in black from the original dies, “made with the gracious and special concession of the Secretary of Communications.” It is essentially a private lithographic printing made with the acquiescence of postal authorities on the government presses at Mexico’s Government Printing Plant.

Said by Schuyler Rumsey Auctions to be one of “approximately 4-5 known to exist,” this example with a tear was estimated at $1,500 to $2,000 in the firm’s October 2015 sale 61 in San Francisco, Calif.

Also, a note in Follansbee’s Catalog of the Stamps of Mexico 1856-1910 states, “All values of this set were printed in black for presentation purposes,” and lists the complete set of 13 at $125. The set was first mentioned in the July 4, 1895, issue of Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News.

Schimmer seems to suggest that Mexico was trying to use these items both as mementos for diplomats, dignitaries, and government bigwigs, and also in place of actual overprinted stamps as specimens to distribute to fellow Universal Postal Union members. The UPU instead requested that Mexico furnish “stamps printed in colors of issued definitives.”

In October 1895, a second installment of the Mulitas was issued on paper watermarked with a fancy interlaced script “RM” (Scott Watermark 153). The 10c denomination was omitted from this second perf 12 series (257-268). Scott and Follansbee again differ in how many perf 6, 6 by 12, 12 by 6 and compound-perforated varieties were issued, with Scott claiming 14 (257a-265a).

Follansbee cautions that “forged perforations are plentiful” and that “some of the more valuable stamps with straight edges have been reperforated.” Panes of all these stamps were printed with straight edges all around, because at least six singles clearly display in the group of 21 shown with this column.

Perforation errors proliferated, especially imperforate pairs and imperforate-between pairs of one sort or another, known on virtually all denominations, as a direct consequence of the woeful deterioration of the available perforating equipment.

As pins broke, were rearranged with gaps between them, and were used to perforate two or more sheets of stamps at the same time, things grew steadily worse. Poorly perforated, hard-to-separate stamps became the norm.

Perforation problems are clearly evident on the 5c Cuauhtemoc stamps pictured in the seventh image above. The singles with the interlaced “RM” watermarked at top and bottom left (Scott 261) show blind perforations on one and blind perfs and ragged margins on the other.

The pairs at right display similar problems, including a fully imperf-between 1898 top-margin pair (283b) above a used “RM” Eagle-watermarked pair perforated 12 by 6 (272), a gauge introduced to try and work around the many broken perforating pins that plagued this series.

Another consequence of unreliable perforation is stamps of the same type with very different dimensions. In the eighth illustration above, for example, the used bottom-right corner margin 1896-97 12c Mulitas stamp (Scott 262) is much wider and shorter than the unused 1897-98 12c (273), which includes a good part of the stamp above it.

At right it appears that some exasperated collector gave up, purchased a multiple of the 1896-97 2c carmine Letter Carrier (258), and trimmed outside the blind perfs all around it to simulate a well-centered stamp.

A printing on paper with the “CORREOS E U M” sideways watermark created a new installment to the series in January 1897. Follansbee lists seven different denominations from 1c to 1p printed on this paper, and Schimmer chiefly notices significant changes and wider varieties in the colors of the mid- and lower-denomination stamps of this printing.

Mulitas with the Eagle and “RM” watermark followed in October 1897 (Scott 269-277a, Wmk. 154). They are perforated gauge 12, along with other makeshift pin configurations.

The final printing appeared in 1898 (Scott 279-298a) on what Follansbee describes as unwatermarked “wove paper with horizontal grain (or mesh pattern).”

There’s far too much great Mexican postal history franked with Mulitas to do much more than mention it, but I think many of the covers are more impressive than the stamps alone.

Better yet, much of this postal history is affordable, particularly if you can figure out how to collect it as Stovner does, tracking down “covers that were transported by foot, mule, stagecoach, train, boat, or combinations thereof, matching the theme on the stamps.”

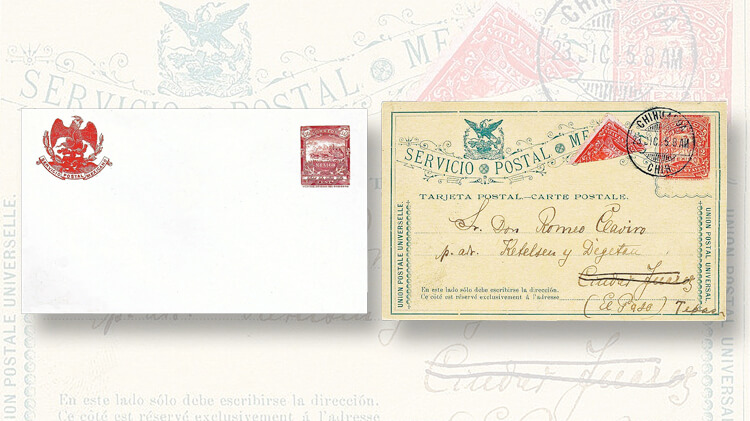

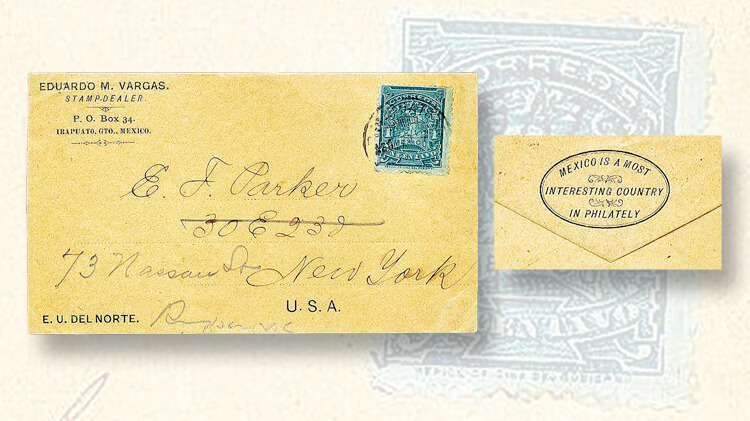

Bland was kind enough to lend me the image of a 1c Letter Carrier stamp paying the circular rate on an 1897 printed notice from a stamp dealer 175 miles northwest of Mexico City, and sent to a New York City stamp dealer who had just relocated to Nassau Street, which would become a mecca for East Coast stamp collectors for several generations. The envelope adds interest with a green oval on the back flap framing the Mexican stamp dealer’s slogan: “MEXICO IS A MOST / INTERESTING COUNTRY / IN PHILATELY.”

Finally, there’s an impressive wealth of postal stationery with the same stamp designs that can add substantially to a Mulitas collection, whether unused, postally used, or perhaps best of all, used with added Mulitas stamps.

Bland showed me the striking, unused 1895 10c red lilac Stagecoach stamped envelope pictured in the ninth image above. The envelope can be had for under $10. However, the 1895 2c bisect (Scott 243a) used on a 2c postal card from Chihuahua to El Paso, Texas, currently catalogs $250.

Collectors captivated by Mulitas postal stationery should seek out Volume II of Arturo Ferrer Zavala’s 2010 Catalogo Enteros Postales de Mexico Vol. II: 1895-1899, the middle of his three-volume set on Mexico’s postal cards, stamped envelopes, letter cards, and more.

His detailed 221-page, full-color catalog does not list prices, but uses a simple rarity scale. Only 500 copies were printed, a limited edition reflected in its prices. The only copy I readily found for sale was offered by Filatelia Hobby of Madrid, Spain, for €55, almost $60.

When you turn the pages in your albums, what sets or series make your eyes light up, and why? Please share your insights and experience and favorites, because the success of this enterprise will rely considerably on collectors willing to share their great sets with us all. Please write to me in care of Linn’s Stamp News or email me.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers