World Stamps

A theory on the numerous varieties of the Jeddah issues of Saudi Arabia

By Ghassan Riachi

The Jeddah issues of Saudi Arabia philately are provisional stamps riddled with overprint, surcharge and handstamp errors.

In this article, all these errors are collectively referred to as varieties.

A few collectors of this area believe that such varieties were intentionally created to sell to collectors.

I have to respectfully disagree. I believe that these errors occurred in Jeddah due to three situations: the lack of experience at the local print shop, the condition of the stamps at the time of overprinting them, and the need to generate additional revenue for the king.

I am using one stamp as an example to demonstrate all three conditions. This stamp is listed in the 2015 Scott Classic Specialized Catalogue of Stamps and Covers 1840-1940 as L80b. The listings for Jeddah issues are found near the beginning of the Saudi Arabia section.

In the grade of very fine, a mint, hinged example of this stamp retails for $450. It is not valued in used condition, and I have not seen a used example of this rarity.

In her 1927 book The Postal Issues of Hejaz, Jeddah and Nejd, D.F. Warin stated that only 50 of these stamps were produced.

The stamp was overprinted in 1925, but its story dates back to 1916, when the Ottoman province of Hejaz was declared independent with the help of Great Britain.

Hussain Ibn Ali proclaimed himself king of Hejaz. The king immediately stopped the use of Ottoman stamps, and plans were set in motion to produce stamps for his new kingdom.

The first Hejaz stamps appeared at the end of 1916.

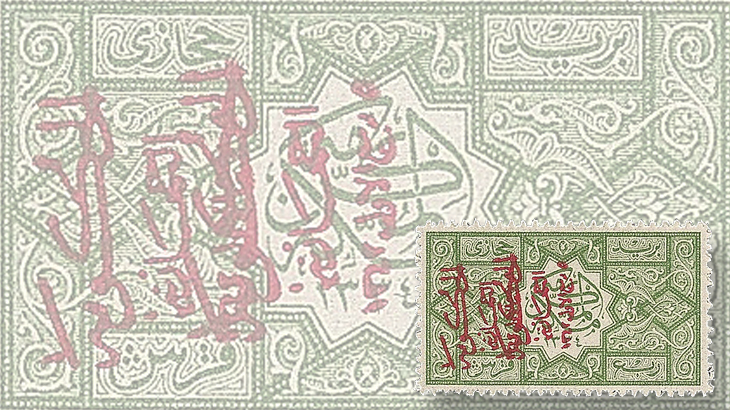

In 1917, Hejaz issued a set of six postage stamps with gauge-13 serrated roulettes (Scott Saudi Arabia/Hejaz L8-L13). The face values of the stamps range from 1 para to 2 piasters. The stamp that is relevant to this article is the green ¼pi denomination, shown nearby (Scott L10).

According to Warin, more than 910,000 basic ¼pi stamps were printed. The stamp was issued in sheets of 50, five columns by 10 rows.

The attractive arabesque design on this stamp is paired with Arabic inscriptions.

The details of the design are a replica of door panels found on El Salih Talayi Mosque in Cairo, Egypt.

The inscription in the top two panels is equivalent to “Hejaz Post.” The two bottom panels give the denomination and currency.

In the central design are the words “Mecca the Honored” with the lunar year “1334,” which is equivalent to the Gregorian years 1915-1916.

The Kingdom of Hejaz, located in the Arabian Peninsula on the Red Sea, contained the two holiest cities in Islam, Mecca and Medina. It also contained the seaport city of Jeddah and the summer capital of Taif.

On the eastern border of Hejaz lay the Sultanate of Nejd, whose capital was Riyadh. The great desert warrior, Sultan Ibn Saud, ruled the country of Nejd. Today, both Nejd and Hejaz are in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Hejaz and Nejd were in conflict with each other. Although both countries were Islamic states, they often argued over religious interpretations. At one point, King Hussain Ibn Ali refused to allow the Nejdis to make the required pilgrimage to the holy cities. The tension between the two states was heightened when Hussain, without consulting with Muslims, proclaimed himself caliph, the guardian of the Islamic religion and law.

Since 1517, the sultan of Turkey had been the caliph. On March 3, 1924, Kemal Ataturk of Turkey abolished the post of caliph. Three days later, on March 6, King Hussain rushed to assume the title.

Hussain’s action angered Muslims all over the world, especially the Nejdis. They felt that this was the last straw between them and Hussain, and that the time had come to put an end to the Hejazi king.

On Sept. 1, 1924, the first city of Hejaz that the Nejdi forces targeted was Taif. The city surrendered Sept. 5.

The Hejazis realized that the relationship between King Hussain and Sultan Ibn Saud could not be fixed and that Hussain’s position put them all at risk.

Fearful of Ibn Saud, and in a move to placate him, the Hejazi people pressured Hussain to abdicate the throne. He gave up his title as king to his son, Ali, on Oct. 3, 1924. Ali became king the next day.

Because there was no outer wall surrounding Mecca, King Ali felt that he and his forces could not defend the holy city, but that they might have a chance in Jeddah.

On the evening of Oct. 13, he ordered his men to sneak out of Mecca. The next morning, the citizens of Mecca woke to find themselves completely defenseless, and that looters had taken over. When the Nejdis learned that the holy city was unprotected, they entered it three days later.

When Ali gave orders to his men to move from Mecca, he also told his officials to take with them whatever Hejaz stamps they could carry. The king knew that these stamps would help bring him much needed revenue to keep his government afloat and to wage his war against the Nejdis.

The stock of stamps included some of the current stamps in use, along with a quantity of the older ones that had been in storage.

Apparently the Hejaz postal authorities had a practice that whenever new stamps were issued, the old ones were not destroyed; they were simply placed in storage to be used later. These old stamps would be retrieved when needed and a new surcharge or overprint would be added.

To invalidate the stamps that had been left behind in Mecca, Ali decided to overprint all the stamps that his men had brought with them to Jeddah. However, there was no government press in Jeddah, so Ali’s men took the stamps to a local print shop to have them overprinted.

There were three problems that affected the quality of the production of these stamps.

The first was the condition of the stamps. Some of them had separated from their sheets, while worms had eaten others. Also, a stock of the stamps had been stuck together haphazardly, gum against gum or gum against face.

The second problem, as noted by Warin, was that the local print shop had no experience in overprinting stamps.

Third, King Ali was not sufficiently paying the shop owner for his work. Consequently, the owner left the work to subordinates, most of whom were illiterate.

The subordinates were in a state of disorder and confusion with these stamps. They applied moisture to the stamps that were stuck together in order to separate them. Unfortunately, this process left numerous stamps stained and others with damage to the face and gum. All of these stamps were overprinted the way they were.

In the confusion, stamps also received inverted overprints, double overprints (both upright, both inverted, or one upright and one inverted) and overprints that are reading either up or down. Overprints also were placed on the wrong stamps or simply overprinted on their gummed side.

Different overprints, handstamps and surcharges were designed to be applied on the various stamps.

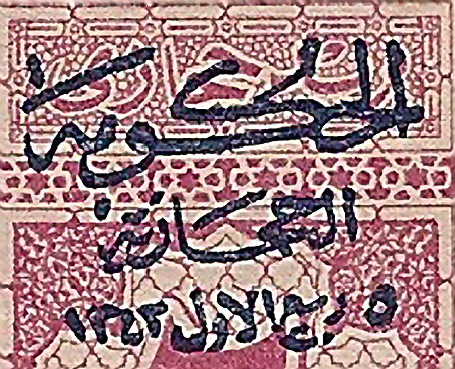

The basic ¼pi stamp received an overprint that was not designed for it, the Jeddah small three-line overprint shown with this column. The top two lines of the overprint are the Arabic words for “The Government of Hejaz.” The third line gives the lunar date of Ali’s accession to the throne. This date is equivalent to Oct. 4, 1924.

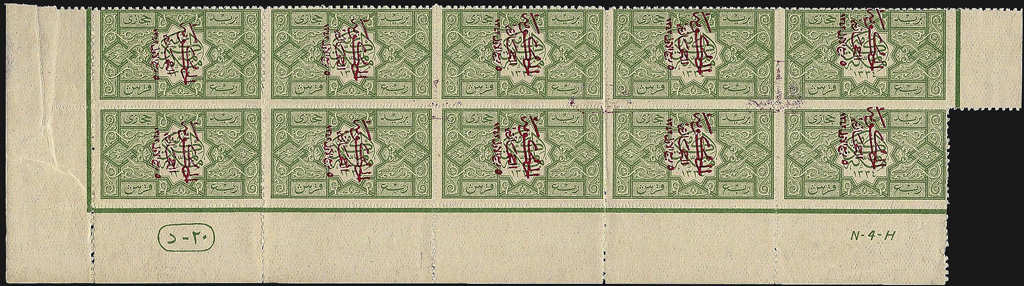

Each stamp was supposed to receive one overprint impression, as shown on the block of 10 illustrated with this column. The obvious error that occurred on Scott L80b was the application of two overprints in red, both reading down.

Because there are two different placement positions of the two overprints (refer to the first and fifth illustrations with this column) on the basic stamps, it is speculated that the 50 examples of Scott L80b came from two partial sheets of the basic stamps.

It appears that there was part of a sheet that adhered to another. Separating them resulted in at least one damaged basic stamp, pictured with this column. The illustration clearly shows the damage took place prior to overprinting.

I speculate that the first overprint impression that was applied to this partial sheet did not cover the intended damaged area on the left of the stamp.

Therefore, a second impression was successfully placed on a part of the damaged area of the stamp. By doing so, instead of throwing away this faulty stamp, it received two official overprints to confirm to the public that it was issued in this condition.

I believe that in order to stay operational, the king needed to raise money as fast as possible for his government and army.

After exhausting many other options, one way to raise additional funds would be by making use of the stock of damaged stamps at hand. The government had nothing to lose by officially issuing them.

Thus, there was no need for quality control at the time of overprinting the stamps. The directive was to ensure that even the damaged sheets and partial sheets were to be overprinted in hopes of selling them to the public.

Luckily, these stamps, with their unusual condition, captured the attention of some collectors.

A dealer in this area told me that in the 1960s and 1970s some collectors owned some of these damaged stamps with various Hejaz markings. The owners could not sell or trade them because other collectors did not like their appearance and believed that the stamps were faulty and not legitimate.

Consequently, collectors began removing them from their collections and then disposing of them. Today, oddly enough, these stamps are the most desirable of the Hejaz stamps.

These varieties were not created to provide collectors with an assortment of errors. They were produced because of the condition of the stamps and the overprinting by unskilled and illiterate workers.

The story behind these stamps serves as a testimony to the creative measures that occur in order to raise money during wartime.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers