World Stamps

As Liberia grew to nationhood, it needed stamps

By Kathleen Wunderly

Liberia’s battles with Ebola virus disease have claimed worldwide media attention since early 2014. It may seem frivolous to focus on the unfortunate country’s stamps, but the EVD epidemic seems to have abated, and you might find yourself curious about this remote country and its philatelic history.

Liberia is on the North Atlantic coast of West Africa, bordered by Sierra Leone, Guinea and the Ivory Coast. It occupies 43,000 square miles, a little larger than Tennessee, and is home to 4.29 million people. Though rich in natural resources — iron ore, diamonds, gold, rubber and timber — it is one of the poorest countries in the world.

The website of the United States Department of State describes the founding of Liberia as being at “the intersection of America’s racial conflict and foreign policy.” In the early 19th century, some Americans believed that freed slaves would be better off by being resettled in Africa. Many slaveholders supported resettlement because they feared revolution by freed slaves. American Negroes, as they were usually called at the time, were themselves unsure, some believing they should remain and continue to struggle for equality, and others thinking a new start elsewhere was desirable.

The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America (commonly referred to as the American Colonization Society) was founded in 1816 to pursue resettlement, supported by Henry Clay, Daniel Webster and other prominent leaders. President James Madison arranged for public funding for the ACS, and in 1818 two representatives went to Africa to seek land for a colony.

Local West African tribes repeatedly refused to deal with them, and not until 1821 was land finally purchased, and then only under coercion by a U.S. naval officer from a military vessel nearby. The local tribes continually attacked the colonists, and fortifications finally were built in 1824.

The social experiment that hoped to forge a nation of people on a continent that had been an ancestral home, and was now to be a place of refuge, reached a milestone: the settlement was named Liberia in 1824, from the Latin liber, meaning “free.” It also became the capital, named Monrovia in honor of President James Monroe, who had supplied government funding. On July 26, 1847, Liberia became a republic, with a constitution, flag, and currency modeled on those of the United States.

Liberia had always relied on private couriers (drums and foot messengers in the earliest days) rather than a formal postal system, but with independence came the belief that the state should control the mails. In 1854 the first post offices were opened in four different parts of Liberia.

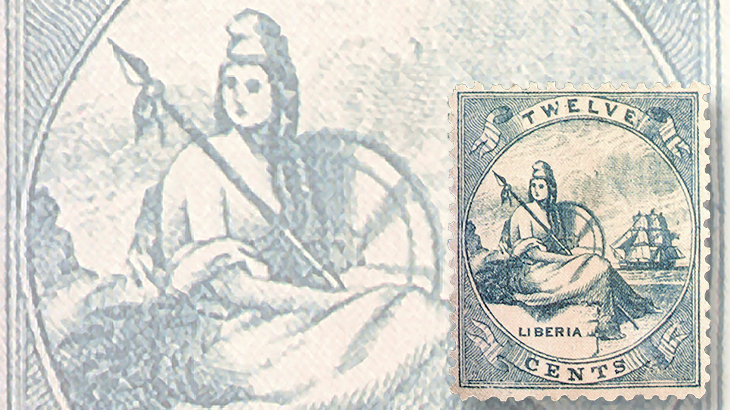

And finally, in 1860, the first Liberian stamps were issued. They were in three denominations and colors (6¢ red, 12¢ deep blue and 24¢ green) but all of the same design.

The design has been known by many names. The Scott Classic Specialized Catalogue of Stamps and Covers 1840-1940 calls it simply “Liberia,” which is what is written at the base of the allegorical female figure depicted. Other philatelic sources refer to the image as Minerva (the Roman goddess of wisdom), Seated Liberty or the Allegory of Freedom.

In his Dictionary of Stamps in Color (1973), James A. Mackay called the design “curiously reminiscent of the reverse side of a British penny — complete with a seated figure of Liberty looking suspiciously like Britannia.”

Manfred Beier’s “Philately of Liberia” website perceptively suggests that the design was inspired by the Perkins, Bacon & Co. die of 1848, first used for Trinidad, Mauritius and Barbados in 1851. These are British colonial keytype issues, in which a basic stamp design is used for multiple postal entities, with different country names and denomination inscriptions.

Look and make your own comparison of Liberia Scott 1-3 with Barbados Scott 1-42 from 1852-73; Mauritius 9-12, 1858-59; and Trinidad 1-55, et al., 1851-82.

In all instances, a robed female figure is seated on a rock, holding a lance and with a shield nearby (though the Liberian “shield” looks more like a ship’s wheel). A masted ship is visible in the background.

The Liberia issues were printed by lithography on thick, unwatermarked paper and perforated gauge 12. Some researchers have stated that the first consignment of stamps sent to Liberia were imperforate; the Scott Classic Specialized catalog lists imperforate pairs for each of the three stamps as Scott 1a, 2a and 3a.

Philatelic literature on Liberia does not seem to discuss two interesting points: Why did Liberian officials suddenly see a need for postage stamps in 1860, and how did they select the printer of the stamps?

Liberia signed a postal convention with Great Britain in 1850 and a further agreement in 1852 for carrying mail between Liberia and Liverpool, but these protocols did not trigger stamps. At the time post offices were set up in the country, in 1854, official letters traveled free, as did “ordinary letters addressed to people residing outside the Republic,” according to Philip Cockrill in Liberia Postal History & Stamps 1835-1945.

What may have been the tipping point was a postal accord between Great Britain, the Republic of Liberia and the United States.

The New York Times reported on Mar. 10, 1858, that an agreement had been reached between the British Post Office and Liberia “which establishes a combined British and Liberian rate of six pence the half-ounce letter as the charge for the conveyance of letters posted in one country and delivered in the other, after the 1st of April next, pre-payment of which is made compulsory” (italics in the original).

The article further stated that the government in Liberia “expressed a desire that letters originating in the United States addressed to Liberia as well as letters originating in Liberia and addressed to the United States, and forwarded through Great Britain, may be fully prepaid in either country to their destinations,” and the U.S. Post Office Department had adopted a regulation to that effect.

Great Britain and the United States had been prepaying mail with postage stamps since 1840 and 1847, respectively, so producing stamps of its own would be a logical move for Liberia, which would be able to use them starting April 1, 1859.

That was a practical reason; another reason may have been a matter of national pride. Liberia’s second president, Stephen Allen Benson, took office in 1856. Benson was born to free parents in Maryland and moved with them to Liberia in 1822. He was deeply interested in expanding the nation (he annexed a colony called Maryland into the republic in 1857) and also in obtaining international recognition for Liberia. During his eight years in office he succeeded in gaining diplomatic status with Belgium, Denmark, the United States, Italy, Norway, Sweden and Haiti. Benson may have recognized the power of Liberia postage stamps as what have often been called “a nation’s calling cards.”

As for the choice of a printer for the new stamps: the reason for this may remain a mystery. Given Liberia’s ties with Britain, including postal ones, it would have seemed reasonable to select one of the established stamp/security printers in London: Waterlow & Sons, established in 1810; Thomas De La Rue & Co., 1813; Perkins, Bacon & Co., 1852; or even the relative newcomer of Bradbury, Wilkinson & Co., 1858.

Instead, the printer of Liberia’s first three stamps was Dando, Todhunter & Smith of London, later doing business as T.F. Todhunter. An 1860 London business directory lists Thomas F. Todhunter, Richard J. Dando and John Henry Smith as partners in a business as booksellers and stationers at 22 Gresham St. in London.

The design of Liberia Scott 1-3 was repeated on a set of five denominations (Scott 16-20) in 1880. Proofs exist of that set that list Dando, Todhunter & Smith as the lithographers and one D. Feldwick as the engraver.

Feldwick, who probably also worked on the first three Liberia stamps, was as unknown at the time in stamp production, as were Dando, Todhunter & Smith. Whitaker’s Almanack of 1876 lists D. Feldwick as an engraver at 16 Holborn, London, available to produce notecards and stationery, and to engrave names on objects such as card cases, opera glasses, and surgical and nautical instruments.

After their service for Liberia’s first issues, neither the engraver nor the printer seems to have ever produced another postage stamp. It would be interesting to discover how they were chosen for their Liberia stamp work. Perkins, Bacon & Co. and Waterlow & Sons, among others, supplied later Liberia issues.

Liberia Scott 1-3 were reprinted several times — in 1864, and 1866-69 — and are differentiated by the type of paper used and placement or absence of framelines. The reprints have Scott numbers 7-9 and 13-15.

Used examples of Scott 1-3 are uncommon, the least common being No. 1, valued at $300 in the Scott Classic Specialized catalog. The imperforate pairs of all three issues also are scarce. A set of mint examples of Scott 1-3 is valued at $475; used, $400. A mint set of imperforate pairs of Scott 1-3 is listed at $1,050.

Covers are uncommon (until the 1920s, the great majority of the population was illiterate, so there was little internal correspondence other than official); the previously mentioned Manfred Beier website says there are fewer than 15 recorded for the first three Liberia stamps.

Collectors beware: Liberia Scott 1-3 were targets of the infamous and talented forger Francois Fournier (1846-1917), as well as a number of other professional and amateur stamp fakers.

MORE RELATED ARTICLES

Headlines

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 3 PMMcMurtrie dismissed as APS education director following Sept. 21 arrest

-

US Stamps

Oct 7, 2024, 12 PMVasiliauskas named president of Mystic Stamp Co.

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 5 PMApgar souvenir card available

-

US Stamps

Oct 6, 2024, 4 PMFirst Continental Congress and U.N. stamps receive Scott catalog numbers